When yachts sail alongside warships

“When we were on vacation on Lastovo in the 1980s, many parts of the island were military exclusion zones,” recalls Antonia Dika from her childhood in Croatia. “Foreign citizens were not allowed on the island at all. To this day, I remember how my father and uncle thought that was a good thing, because that meant more fish for them,” says the architecture scholar from the University of Arts Linz.

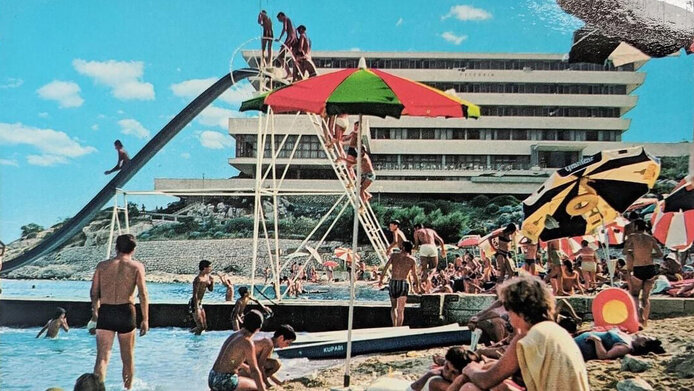

Today, the Croatian island of Lastovo is one of six case studies that Dika is conducting together with cultural studies researcher Anamarija Batista as part of the project “Collective Utopias of Post-War Modernity.” Lastovo, Vis, Brijuni, Lošinj, Šepurine, and Kumbor all have one thing in common: Military coastal defense installations from the Cold War coexisted with emerging mass tourism. Yugoslavia invested heavily in tourism along the eastern Adriatic coast, building massive hotel complexes and cultural centers alongside military installations - a bizarre picture that was normal for several decades. And a history that is being forgotten.

When the military meets tourism

“Our focus was on the impact of the dual phenomena military and tourism on the local population and communities,” says Antonia Dika. Interaction between the two different uses varied in the case studies documented in the project. While only locals had access to Lastovo and Vis, the military installations on Lošinj were close to tourist resorts. “It was perfectly normal to see yachts next to warships,” explains the researcher. The contradictions inherent in this coexistence are particularly interesting for the researchers.

In just a few years, the coastal region of Yugoslavia developed into a popular post-war tourist destination. At the same time, the country was arming itself against a potential NATO attack. Rijeka-born architect and researcher Antonia Dika followed the traces of a society between bunker and beach and what remained of it.

About the project

On the one hand, the Yugoslav population was supposed to maintain military secrecy. On the other hand, people were encouraged to provide hospitality along the Adriatic coast to present Yugoslavia in a positive light. This led to a paradoxical situation: “They had these defensive structures against the west, and then tourists from these same NATO countries came to water ski in front of the facilities,” says Dika. The view of the horizon becomes a symbol of war and peace: “So while some were waiting for the enemy and shoring up their defenses, others were relaxing and enjoying their vacations.”

Symbolic architecture

Buildings like the Hotel Haludovo on the island of Krk are now well-known “Lost Places,” forgotten buildings that remain standing as a reminder of the past. But their history also documents ideals. In the early 1950s, the foundations for a tourism characterized by socialist ideals were put in place in what was then Yugoslavia. This tourism was intended for the local population, who at that time lived mainly from fishing and farming. The construction of a road along the eastern Adriatic coast in the late 1960s created a connection to the west, making mass tourism possible. Suddenly, well-known architects were commissioned to build innovative resorts. “These ostentatious hotel complexes were meant to be Yugoslavia's calling cards,” says Dika. They were intended to show how well the nonaligned solution worked in Yugoslavia during the Cold War period.

The emergence of tourism was politically motivated. At the same time, there were cultural centers set up by the military with events ranging from concerts to cinema screenings. “Tourists came in contact the civilian population there,” says the researcher. Because of these ideals, the privatization of tourist areas is based on a different tradition than in Austria. Mass privatizations like on the shores of many Austrian lakes would be unthinkable in today's Croatia and are not acceptable to the civilian population. A bath towel designed by Antonia Dika and Anamarija Batista as an interventionist part of the research project was also very well received by the public. It says: “The seashore is common property – and common property belongs to everyone.”

Learning from the past

The break with the socialist tourism past is closely linked to the war in Yugoslavia and the rise of capitalism. Many of the former vacation resorts stood empty during the war or were used for refugees. “Why some of them still stand empty usually has to do with unregulated ownership. This also applies to the military facilities,” says Dika. Thanks to a greedy few, many of these areas have become disputed zones. The population is more likely to mourn the tourist facilities because they see these as their own. Through her research in archives and online forums Dika gained access to contemporaries, who described the atmosphere at the time. “Former soldiers turned out to be the biggest source of information, as they came to these resorts from all over Yugoslavia, but were then scattered all over the world after the war and now share information about them through social networks,” says Dika.

When the researchers presented their findings at the 2023 exhibition “The Distance View“ in Sarajevo, they finally had the opportunity to piece together many fragments and place them in a spatial context. “This allowed us to get a picture of the past and present that unites all these contradictory perspectives.” At the same time, Dika and Batista also worked on artistic aspects of the project in cooperation with photographer Zara Pfeifer, artists Goran Škofić and Olaf Osten, musician Emir Kulačić, and filmmaker Arthur Summereder. The resulting works were also shown at the exhibition in Sarajevo.

Personal details

Antonia Dika works as an architect, urban planner, and researcher in Vienna. As a senior scientist at the University of Arts Linz, she is heading the art-based research project “Collective Utopias of Post-War Modernism” (2018-2024) which was funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) with €397,000. Dika has taught at several universities and has received numerous awards. She also works for the Gebietsbetreuung Stadterneuerung, an urban renewal department of the City of Vienna.