Intensive research work

The project, which was funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF and Lower Austria, recorded all camps that were in existence for at least three weeks. “Without that selection yardstick, we would not have found just 247 camps, but probably a number in excess of one thousand,” explains Katharina Bergmann-Pfleger from BIK, since, particularly at the end of the war, there were many short-term structures serving as shelters for the population as the Red Army approached. The project findings required long and in-depth research. Bergmann-Pfleger cooperated intensively with municipal, city and regional archives, as well as the national archives. In addition, the researcher engaged in literature analyses and sifted memories of contemporary witnesses, with some of whom she also was able to conduct interviews.

Research activities that had originally foreseen work in Moscow archives had to be abandoned due to the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine. Nonetheless, Russian archival material, which was available from earlier projects at the BIK, could be vetted for camp information.

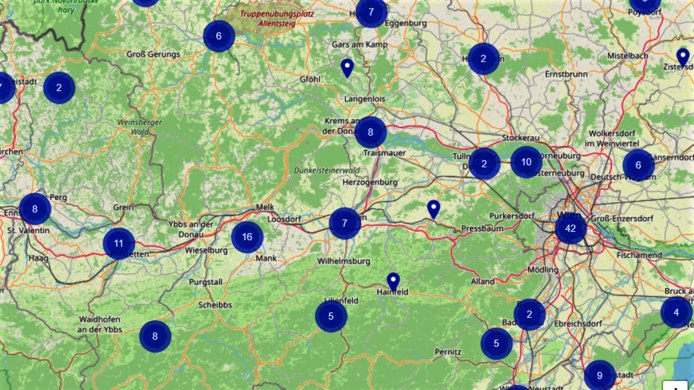

“But we probably haven't identified all the camps,” says Bergmann-Pfleger. That is one reason why she does not consider the research project as being completed. She expressly welcomes support from the general public in the form of tips, images or information. Perhaps the map will raise awareness of traces from the post-war period. Even if many things have become invisible, a few traces do still exist – such as the street name Lagergasse or remnants in forests from the forced repatriation of Cossacks.