Depression and mind control

In principle, people are able to influence their own thoughts and emotions – an ability known as cognitive control. Underlying this ability are neural processes in the frontal and lateral lobes of the brain, which are fundamental to a variety of important functions such as making decisions, solving problems, regulating negative emotions, suppressing impulses, and adapting behavior as dictated by different situations.

“In psychotherapy, we often see that people with depression know that typical thought spirals are harmful to them, but find it difficult to snap out of them,” notes Stefan Duschek, psychotherapist and professor of health psychology at UMIT TIROL. “This has to do with cognitive control – the ability to control and change one's own thoughts.” About 15 percent of the population experiences one or more depressive episodes during their lives. According to Duschek, the ability to interrupt stressful thoughts and negative feelings is a key to understanding and treating the disorder.

Collaborative project between Tyrol and Bonn

In order to explore whether and in what form depression actually impairs cognitive control, Duschek's team has worked with researchers from the University of Bonn on the further development of an established psychological test – the antisaccade task. Test subjects are asked to control their eye movements in a specific way while being shown photos of emotional facial expressions on a screen. Eye tracking is used to record eye movements, while electroencephalography (EEG) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) reveal when and in which areas of the brain the underlying processes take place.

The project entitled “Neural Correlates of Proactive Control in Major Depressive D” is funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) and the German Research Foundation (DFG). Initial studies with healthy individuals have confirmed that the method is appropriate for investigating brain processes involved in cognitive control. In addition, data from over 200 individuals with and without depression have already been collected in both Hall in Tirol and Bonn and are now being evaluated.

About the project

International researchers are investigating whether people with depression have difficulties with proactive control—that is, focusing their attention on expected events. EEG, fMRI, and eye tracking are used to analyze the underlying brain processes in patients and healthy control groups. The aim is to better understand how cognitive and emotional factors contribute to depression.

Telling eye movements

The experiments focus on proactive cognitive control, i.e. the ability to focus attention on an expected event, mentally prepare for it, and plan an appropriate response. “It is our hypothesis that people with depression have difficulty doing just that,” says Duschek. “Because proactive control is exacting and requires a great deal of attention and working memory.”

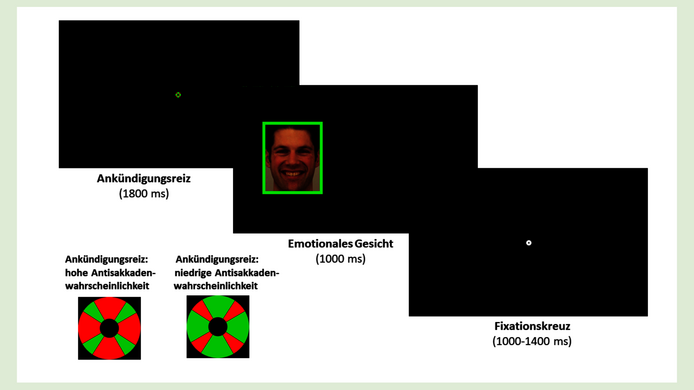

This is the set task: a colored circle appears on the screen – mostly green or red – indicating whether the person should look at a face appearing to the side of the circle (mostly green) or look away from it (mostly red). The person mentally prepares for the expected requirement. Then an image of a facial expression with a green or red border appears. The border makes it clear which eye movement is actually required: looking at or away from the image. Looking away, known as an anti-saccade, is a prime example of cognitive control. This requires suppressing the automatic reaction (“Look!”) and actively making the eyes move in the opposite direction. These processes can be prepared in advance of the image's appearing, i.e. proactively controlled.

“It sounds complicated, but it's designed in a way that you'd respond correctly in three out of four cases,” says Duschek. The psychologists are particularly interested in the data from the EEG and fMRI, showing which areas of the brain become active, when, and to what extent. “We want to find out two things: first, the extent to which cognitive control is impaired in people with depression. And second, the role played by different facial expressions, i.e. whether controlling emotional information entails a particular challenge.”

Joy, fear, anger, sadness

Faces are particularly powerful stimuli. “Emotional facial expressions have proven valuable in psychological experiments because the human brain processes them particularly well and at lightning speed,” explains Duschek. “A sad or fearful face automatically and intuitively triggers an emotional response.” The psychologist suspects that people with depression find it particularly difficult to process negative emotional information such as sad faces.

In a second experiment, the team combined fearful and happy facial expressions with the words “fear” and “joy,” with the words either matching or contradicting the images. For example, a happy face was shown at the same time as the word “fear”. Test subjects with and without depression were asked to identify the facial expression but ignore the word. The result: people with depression made more mistakes, but only when the word and the face did not match. “This suggests that they have problems processing conflicts between different emotional information. Again, this is a problem of cognitive control,” says Duschek.

Distorted perceptions in depression

“People with depression often interpret situations differently,” reports Duschek. “This does not affect everyone equally, but sufferers show clear tendencies to view themselves, their environment, and the future in a more negative light.” By way of example the psychologist notes that many people are annoyed by an everyday argument for a brief moment, but will quickly let go of the negative thoughts and feelings. “People with depression tend to relate strongly to such an argument,” says Duschek. This can lead to brooding or spiraling thoughts, which then trigger negative feelings and other depressive symptoms.

“Blaming yourself for negative things and consequently experiencing feelings of guilt is very typical of depression,” notes Duschek. In this context, researchers need to distinguish between two levels: one concerns the content of thoughts, i.e., how or why those affected evaluate themselves and their environment negatively. Psychotherapy can address this content effectively. On the other hand, it is crucial to understand the fundamental mechanisms by which we control our thoughts and emotions and how this process can become impaired. This is precisely the subject of the present research project, designed to help us better understand the onset of depression.

Understanding the control mechanisms – and perhaps strengthening them

“Understanding cognitive control is extremely important and helps us comprehend why some people cannot stop stressful thoughts, let them go or counteract them through constructive thoughts,” says Duschek. Difficulties with cognitive control also occur in other mental disorders, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety disorders, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. A better understanding of these processes could also contribute to improving therapeutic strategies that help those affected to interrupt brooding and negative thought patterns and strengthen positive ones. The ability to effectively control thoughts and feelings is an important mental health resource.

The next step in the research project is to evaluate the data obtained from the 200 people with and without depression who were examined in Hall in Tyrol and Bonn. Initial findings are expected for spring 2026. Then the question will be: how can we not just grasp how to deal with stressful thoughts, but actually enhance the ability to do so?

About the researcher

Stefan Duschek is head of the Clinical and Health Psychology department at the Institute of Psychology at UMIT TIROL – Private University for Health Sciences and Technology. His research focuses on cognitive control and emotion regulation in mental disorders, the biological, psychological, and social foundations of chronic pain, as well as body and symptom perception. Set to run until April 2026, the international WEAVE project “Neural Correlates of Proactive Control in Major Depressive D” is awarded roughly EUR 198,000 in funding from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF).

Publications

Affective Modulation of Preparatory Cognitive Activity, in: PsyCh Journal 2025

Neural Correlates of Proactive and Reactive Control Investigated Using a Novel Precued Antisaccade Paradigm, in: Psychophysiology 2025