Our complex brain in simple terms

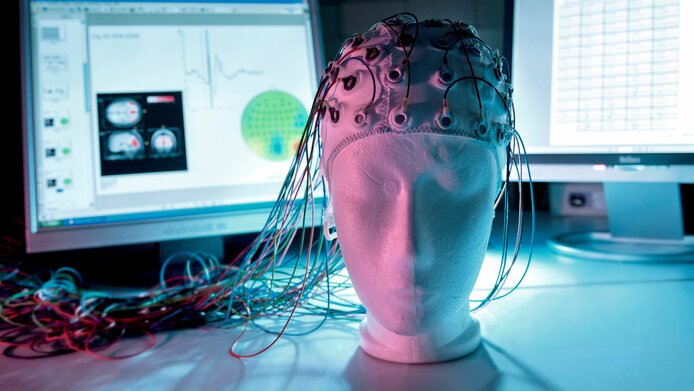

“Many people wonder why we think the way we do, how we feel things, or why we behave the way we do. While intriguing, these questions are also very difficult to answer. In cognitive neuroscience we explore the answers: we try to understand what happens in our brains when we think, remember, or feel something,” says Pavlos Topalidis. This neuroscientist specializes in sleep research, which is one part of this large and relatively new field of research. In the sleep laboratory of the Center for Cognitive Neuroscience at the University of Salzburg (CCNS) and at the Christian Doppler Clinic, Topalidis conducts research on sleep quality, on how it can be measured, and on the connections between sleep and disorders such as epilepsy.

How can one explain neuroscience research to the general public?

Topalidis is also looking into another issue, namely explaining neuroscience to laypeople in an easy-to-understand way, answering their questions, showing them how research works, and possibly inspiring young people to opt for this field of study. His initiative gave rise to the project “From Brain to Mind,” funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) in the context of its “Science Communication” program. The project is based on the scientific findings of an FWF doctoral program. This training program, which ran for more than ten years, took place at the University of Salzburg under the direction of Manuel Schabus, professor of cognition and consciousness and founder of the sleep laboratory. Students were able to conduct research on various cognitive neuroscientific processes such as language, reading, consciousness, behavior, and depression. Topalidis was one of these students: “It was a huge funded project, and I wanted to communicate the extensive research results to the general public.”

Dive into mind and brain research

Media formats and target groups

The first decision concerned the tools of science communication, notes the neuroscientist: “When you organize an event, it takes place once, witnessed by a few people, and then the content is no longer at hand.” That's why the team in Salzburg opted for online communication with audio and video, because it is available for a long time on the web for anyone interested and also incurs relatively low costs.

The next step was to define target groups and media formats: a documentary film for explaining neuroscience to a broad audience in an easy-to-understand way. “The film is also aimed at schools in order to get young people interested in research,” says Topalidis. The film production was followed by in-depth podcasts that delve into individual areas of research and bring complex material to life through personal storytelling.

Plans foresaw a third format consisting of short video clips explaining scientific publications. Following experience gathered, the team decided however not to follow through with it, explains Topalidis: “In the world of science, published papers are discussed within the community, and we wanted to open these discussions up to a wider audience. Our idea was for researchers to explain individual publications in a short video. We found, however, that it was difficult finding researchers ready to do that. Perhaps we are just a bit too premature, because I do see a tendency for researchers to be interested in presenting their work to the public in easily understandable terms.”

Creating interest through storytelling

The science communication project is still work in progress, but some things have already been implemented. The documentary on cognitive neuroscience is aimed at interested viewers of all ages and does not require any prior knowledge. It will be about 30 minutes long and is planned to be released in April.

Since December 2025, there has been a “Brain to Mind” podcast once a week. Professors and PhD students present stories of scientific work and include personal aspects. For example, one student reports on her research into sleep disorders and the necessary work-life balance in her work. Another student is doing research on eating habits and talks about how he is trying to discover the mechanisms behind why we choose certain foods. “The podcasts are deliberately kept very personal. We tell stories about the people behind the research, how they feel about it, what motivates them. It is these personal stories that create role models and make science interesting and approachable,” science communicator Topalidis says with conviction.

Lessons learned for science communication

Topalidis also talks about a few challenges during implementation. “I'm a neuroscientist, but I am not an expert in science communication. This is something I have in common with others who would like to communicate research results.” The following tips are based on the experience he gathered:

- The project should have a designated contact person from the field of science communication. At the start of the project, this person will provide support with issues such as defining target groups, selecting formats (how best to address the target groups), and public relations (how to make the results visible, such as how to reach schools, for instance). During the course of the project, this person should also ensure that the content can be understood by non-experts.

- Public relations work is not just a topic for a project, but an ongoing task and responsibility for universities. It is important for funds to be available also for infrastructure, such as tools for the production of podcasts or films. Topalidis was able to use a studio at the University of Salzburg for producing the podcast, which is run on the initiative of teachers in the media department. External support was brought in for the production of the documentary.

- Guidelines and rules for public relations, which are documented in most university communications departments, are also helpful. For film production this includes questions such as: is filming during lectures permitted, which requests must be submitted to whom, or what data protection rules apply?

From Pavlos Topalidis's point of view, science communication is an increasingly important task. He himself has learned a lot about public relations in a research context, and he now wants to share this experience with other research institutions.

The project

The “From Brain to Mind” initiative aims to find new ways to improve science communication. The focus is on cognitive neuroscience, with the aim of communicating advances in research to a broad audience in a comprehensible and accessible way. One objective is to demonstrate the social benefits of research. Secondly, the project intends to spark interest in STEM subjects by having researchers talk personally about their work and motivation.

From Brain to Mind is funded under the FWF’s “Science Communication” stream and is set to run until July 2026.

About the researcher

Pavlos Topalidis received his doctorate in sleep research from the University of Salzburg. After completing his bachelor's degree in psychology, he specialized in cognitive neuroscience. He is currently conducting research at the Christian Doppler University Hospital and in the Sleep Laboratory of the Center for Cognitive Neuroscience Salzburg (CCNS). He is particularly interested in the quantification of sleep and the measurement of sleep in various patient groups with sleep disorders, such as epilepsy patients.

In addition to his academic work, Topalidis is interested in the complementary roles of academia and industry in advancing sleep science. In this context, he contributes to research and development at sleep². The spin-off of the University of Salzburg aims to enable reliable, home-based sleep assessment using wearable technologies, thereby reducing the reliance on complex laboratory infrastructures.