Why the liver deteriorates with age

While, as a rule, dead bacteria from the gut microbiome are simply excreted, this is not always the case. Under certain circumstances, parts of these bacteria can enter the body's bloodstream and cause serious organ damage. Gram-negative bacteria, which have an outer membrane layer, contain toxins – known as bacterial endotoxins – that are released after the bacteria decay.

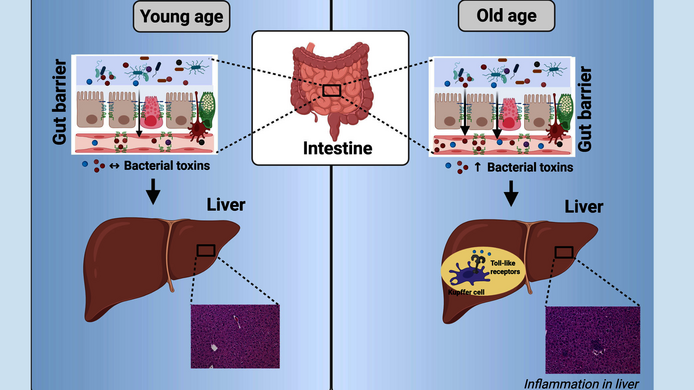

In healthy people, a layer of cells and proteins in the intestinal wall prevents the toxins from entering the adjacent tissue and bloodstream. However, high alcohol consumption in particular, but also foods rich in fat and sugar plus other factors, can make this barrier more permeable, with the result that the bacterial endotoxins trigger inflammatory reactions in the body. Among other things, they also contribute to the development of fatty liver disease.

The intestinal barrier becomes more permeable with age

Eventually, the intestinal barrier function weakens in almost everyone. The number of so-called tight junction proteins, which close the gaps between cells in the intestinal wall, decreases significantly with age. As a result, bacterial endotoxins find it easier to pass through, causing mild but persistent inflammatory reactions in the body. In the FWF-funded project “Aging and Bacterial Endotoxin,” researchers from Austria and Germany investigated how these processes contribute to the weakening of important organ systems in the later years of life.

Together with her team, Ina Bergheim, Professor of Molecular Nutritional Sciences at the University of Vienna, focused on the processes in the liver. Her colleague Annika Höhn from the German Institute of Human Nutrition Potsdam-Rehbrücke (DIfE), examined what effects this phenomenon has on the pancreas. Both organs are important regulators of metabolism and digestion and are sensitive to persistent inflammatory stimuli. These can ultimately lead to scarring, known as fibrosis.

Understanding aging processes

Aging is often accompanied by a loss of organ function, accompanied by chronic inflammation and changes in the immune system. The research conducted by Ina Bergheim and her team at the University of Vienna is helping to improve our understanding of age-related degenerative processes and to develop preventive measures based on this knowledge.

Figure created in BioRender.com © Brandt/Staltner

Basis for therapies and prevention

“Aging is accompanied by a gradual decline in organ function – even in healthy people who do not consume large amounts of alcohol. We are investigating the molecular mechanisms and the extent to which bacterial endotoxins contribute to this age-related degeneration,” explains Bergheim, outlining the research goal pursued by the team. A more thorough understanding of these mechanisms could not only pave the way for new therapies, but also indicate means for slowing down these chronic inflammations through an appropriate diet.

In the project, the researchers focused on the question of how strongly the immune system in the liver and pancreas actually responds to the age-related presence of bacterial endotoxins. Can it be proven that they trigger inflammatory reactions? And what happens when this immune response is switched off – do the typical signs of aging in the organs also change? This study was based on a mouse model in which certain receptors of the body's immune system are absent.

Outwitting the immune system

“This involves what are known as toll-like receptors (TLRs), which are primarily found on monocytes and macrophages – cells that are part of the innate immune system and fulfil a guardian function in the body. In the liver this also includes Kupffer cells, which are phagocytes that specialize in controlling the blood flow in this organ,” explains Bergheim. “In our mice, all TLRs that are known – or even suspected – as being relevant for the recognition of bacterial endotoxins were switched off. Their immune system was therefore unable to respond to the bacterial components and trigger a concomitant inflammatory response.”

The mice were also given inhibitors that suppress additional TLRs as soon as they reached the age of about 16 months – i.e., when they became “old”. This constellation helps to better classify liver diseases that nevertheless occur: if the damage persisted despite the TLR blocking, it was thus not TLR-mediated but attributable to other functional disorders or aging processes.

Experimental slowing of organ aging

The result was unambiguous. “The mice whose TLRs were specifically switched off showed consistently fewer signs of aging in the liver. Inflammation and resulting fibrotic changes decreased significantly compared to mice with normal TLR function,” Bergheim reports. The bacterial endotoxins could hence be clearly identified as a major factor in age-related organ degeneration.

Blood samples also show that harmful bacterial components increase with age even in healthy people of normal weight. It seems likely that their effect is even more serious in sick people. “Of course, with humans it is not an option to simply switch off parts of the immune system in the course of therapy in order to prevent age-related damage,” notes Bergheim.

“However, if we could find a way to enable the immune system to continue to respond adequately whilst chronic stress is suppressed, a lot would be gained.” Whereas the aging of organs cannot be halted, a better understanding of the mechanisms of inflammation may help to slow it down somewhat.

About the researcher

Ina Bergheim was appointed Professor of Molecular Nutritional Sciences at the University of Vienna in 2016. Earlier waystations included positions at Friedrich Schiller University in Jena, the University of Hohenheim in Stuttgart, the University of Louisville in Kentucky, and the Robert Bosch Hospital in Stuttgart. Her research focuses on molecular mechanisms in the field of alcohol-induced and age-related liver diseases. Running from 2021 to 2025, the project “Aging and Bacterial Endotoxin” has been awarded EUR 359,000 in funding by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF).

Publications

Aging-related decline in the liver and brain is accelerated by refined diet consumption 2025

The Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction as Driving Factor of Inflammaging 2022