How viruses overcome barriers

Doris Wilflingseder has been exploring for decades the complex fight put up by organisms against invaders such as viruses. A pathogen attack via the skin or mucous membranes triggers a dynamic process by the host's immune response, and it is still not understood what exactly happens during this process. Wilflingseder focused her research on HIV and wanted to understand how the virus invades the human body. In a project funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF, she discovered that the virus is enveloped by the body's own proteins which alter the surface of the pathogen, thereby facilitating its entry into dendritic cells, which are important players in the immune system’s defense mechanisms.

“In the laboratory, we incubated HIV in both serum and seminal fluid and saw that the virus actually acquires a protein corona because it interacts with the proteins in these fluids. The proteins in this case were predominantly complement proteins,” explains Wilflingseder, who has been conducting research for over a year at the newly founded Ignaz Semmelweis Institute in Vienna – an interuniversity science hub with a focus on infectious diseases and pandemics.

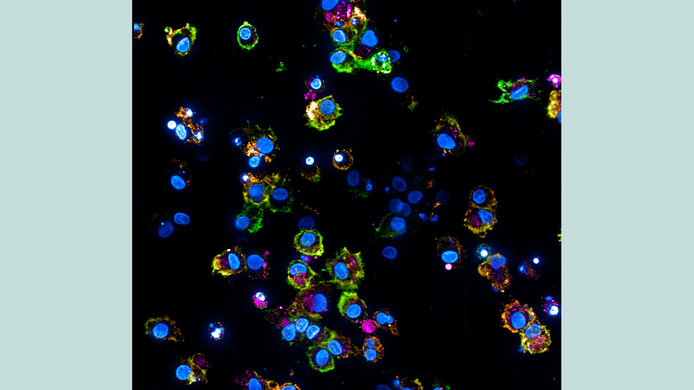

An additional role is played by HIV-specific antibodies which develop in later stages of infection. “That's why we also test viruses that are covered with such antibodies.” The team analyzed how cellular processes differ depending on whether a cell takes up a naked virus, a complement-coated virus, or an antibody-coated virus.

The findings reveal clear differences. “We have seen that complement-coated viruses trigger a strong immune response via dendritic cells,” notes Wilflingseder. In contrast, dendritic cells loaded with naked HIV particles respond with a weak immune response, since in this case the virus is blocked by restriction factors in the cell. If, on the other hand, the cell comes into contact with a virus that is protected by a “protein coat,” the virus can use mechanisms to circumvent the restriction factors.

This pattern corresponds to what is observed in the acute phase of HIV infection. “At the beginning, the complement system tries to keep the virus in check until HIV-specific antibodies are added later on.”

One Health – One Planet

Infectious diseases can cause serious illness. Every year, they cause millions of deaths worldwide. Climate change, close contact between humans and animals, limited habitat, and globalization also increase the risk of new outbreaks and pandemics.

Basic research is essential for a better understanding of infectious diseases. Knowledge about pathogens and immune responses forms the basis for prevention, vaccines, and medicines.

From HIV to SARS-CoV-2

When COVID-19 hit the world, Wilflingseder shifted her research focus and was able to draw on insights from HIV projects. “We transferred our questions about HIV to SARS-CoV-2.” Her approach centers on the mucosal barrier, where dendritic cells are among the first to come into contact with invading viruses. “The idea is to target specific receptors and use them for future immunization or therapy,” says Wilflingseder.

Cell models instead of animal experiments

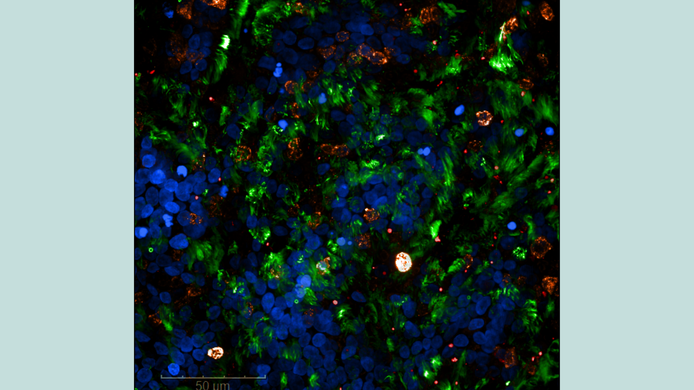

It was actually years ago, while still at the Medical University of Innsbruck, that Wilflingseder began developing specialized cell models. For HIV, her team had models with dendritic cells and T cells, followed later by mucosal models. In Innsbruck, the team added another focus. “The director of our institute, Cornelia Lass-Flörl, took an interest in fungal infection of the lungs and asked me if I would like to develop a lung model.” This led to the creation of an air/liquid phase model that produces mucus and contains cilia. “We established and then optimized and standardized this model,” reports Wilflingseder. The group integrated immune cells such as dendritic cells and macrophages into this system in order to develop a realistic model of the respiratory tract.

This preliminary work proved to be of great advantage when research on SARS-CoV-2 began. With the support of the Department of Internal Medicine in Innsbruck, the team received the first virus samples from patients as early as March 2020. “In the laboratory, we investigated how the viruses interact with these highly developed respiratory barriers,” says Wilflingseder. They observed an overproduction of mucus, a finding that has also been described in severely ill COVID-19 patients.

In addition, the researchers investigated whether epithelial cells, which represent the first physical, chemical, and mechanical barrier of our body, can trigger inflammatory reactions without an immune cell. “We investigated whether epithelial cells also produce complement factors and found that this is indeed the case. Complement activation causes severe inflammation,” explains Wilflingseder. These results also corresponded to clinical observations of severe COVID-19 cases, where there was an overproduction of complement factors. Therapeutic experiments in cell culture showed that the excessive immune response could be stopped by blocking the complement system.

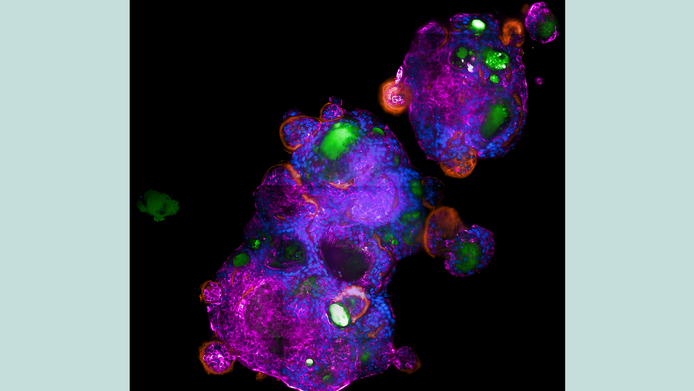

Organoids and the special immune system of bats

Wilflingseder, the inaugural professor of infectiology at the Ignaz Semmelweis Institute in Vienna, and her team started to develop organoid models of various animal species. “In Innsbruck, we worked exclusively with the human system. Now we are developing models of different species that are relevant for zoonotic viruses (i.e. viruses that are transmitted from animals to humans). In the next few years, we also want to investigate what happens when a virus spreads from one species to another.” The research community suspects that this was the trigger for the coronavirus pandemic. However, Wilflingseder does not want to commit to a specific virus, as she is also interested in fungal infections or co-infections, since these often have serious consequences, especially in the case of HIV.

Bats are of particular interest to the researchers in Vienna. “Bats are generally fascinating because they hardly ever develop viral infections,” says Wilflingseder. Their metabolism differs greatly from that of humans: extreme temperature fluctuations, high energy consumption when flying, and a greatly reduced metabolism during rest periods. She is especially intrigued by the complement. “It is a very old, conserved system, and complement proteins have already been identified in sea urchins.” Studies show that bats have significantly higher complement concentrations in their serum than humans, and the group would like to investigate this peculiarity more closely.

Antiviral sprays block viruses

Another project is dedicated to the question of whether simple measures such as antiviral sprays can slow down viruses. At the beginning of the pandemic, the team investigated the effect of various mouth and nose sprays and tested them on an air/liquid phase model of bronchial epithelial cells. They sprayed the preparations from a defined distance, then infected the tissue and analyzed it over several days. “We saw that there was a good protective effect for up to two hours after infection.” According to the manufacturer’s information in the package, prescription-free sprays available from pharmacies can be used six times a day, i.e., approximately every two hours.

New routes in drug development

“Replacing animal testing is extremely important to me,” emphasizes Wilflingseder. When it comes to drug development, the US have already introduced some changes. For decades, drugs had to be tested on two markedly different animal species. The FDA has now modernized this system: today, pharma companies are allowed to use the most effective method. “Cell culture systems can be used if they are more predictive, or they can be combined with in-silico models.” The development of induced pluripotent stem cells and sophisticated organoids has permitted enormous progress. By now there are many models that enable better predictions than animal testing.

European regulators are also moving down this route. The EMA and EU funding programs are increasingly supporting “new approach methods” and non-animal testing systems. Doris Wilflingseder considers this to harbor great potential. Constructive collaboration, such as it will be practiced at the Austrian 3R Days 2026, enables researchers to find inspiration from one another and work together to reduce animal testing. “It will not be possible to replace animal testing overnight, but we can do a great deal to reduce it,” Wilflingseder says with conviction. In 2021, her cell culture models earned her the State Award for the Promotion of Alternative Methods to Animal Testing.

About the researcher

Doris Wilflingseder is an Austrian immunologist and infection biologist. She conducted research on dendritic cells and HIV-1 at the Medical University of Innsbruck and at University College London, among other institutions.

In 2024, she was appointed inaugural professor of infectiology at the University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna, at the newly founded interuniversity Ignaz Semmelweis Institute. Her research focuses on immunocompetent 3D barrier models for studying the penetration and processing of pathogens. Praised as a leading voice for animal-free research, she was awarded the Austrian State Award for the Promotion of Alternative Methods to Animal Testing in 2021. Wilflingseder is also involved in the RepRefRed Society and the Austrian 3R Center for the promotion of alternative biomodels.