What EU funding reveals about Europe's migration policy

Europe is a center of global migration movements, and the number of asylum applications rose sharply at times as a result of the Syrian civil war and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Although there was rising pressure on the EU over the last 15 years to regulate immigration more strictly, there were only incremental changes in the concomitant legislation. On the other hand, funding for migration management has been massively increased. The EU budget for the period 2021 to 2027 includes more than twice as much funding for migration, asylum and border protection than in the 2010s, i.e. EUR 22.7 billion.

Federica Zardo from the University for Continuing Education Krems explains the reason for this discrepancy: “Legislative proposals have to be passed through many bodies. Moreover, migration is a controversial topic among the EU member states. That is why we only see gradual adjustments at the legislative level. Funding, on the other hand, is easier to steer.”

The autonomy of money

“Governance through funding” – this is how experts describe policy-making based on funding. The budget of financial instruments – including the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund (AMIF) – comes from the EU budget. The funding goes to member states, third countries, NGOs, UN institutions or EU agencies such as Frontex. Depending on the funding program, the recipients use the money for issues such as improving asylum procedures, combatting the causes of migration, fostering integration or border protection.

About the project

Following the money: Political scientist Federica Zardo and her team are investigating the evolution of EU financial instruments for the management of migration and asylum since 2000. One of the central aspects of the project is to explore the rationales behind the planning, allocation and use of funding.

In her research project “Analyzing change in EU funding for migration and asylum (MigFund)“, Federica Zardo is investigating what pathways the EU funds take. The political scientist knows that this reveals a lot about the goals of those who disburse them. “The financial instruments provide some leeway for designing migration policy – even if legislative changes are progressing slowly. This is what we call the 'autonomy of funding'“.

Trend towards more restrictive measures

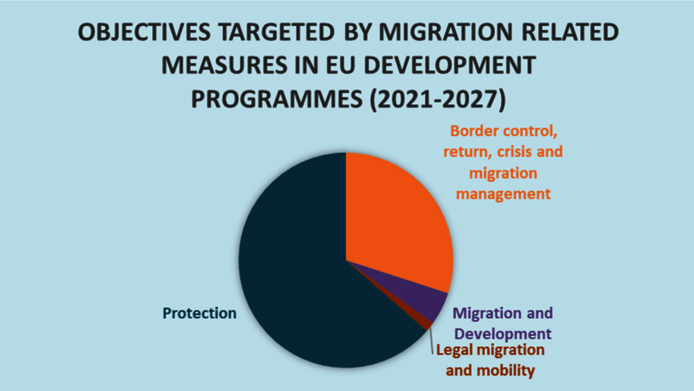

In order to understand how the objectives and use of the funds have changed over time, Zardo analyzed all funding documents since 2000 and answered a number of questions: are the funds used for measures designed to ward off migration movements or for programs for integration and legal immigration? And are these measures implemented within the EU or in third countries?

This is what the data shows: the caesura brought about by the upsurge in asylum applications around 2015 is reflected in the EU financial instruments. “On the one hand, the funding amounts have skyrocketed as expected. At the same time, the objectives became measurably more restrictive,” says Zardo. “Even programs that actually address development aid and the causes of flight increasingly include measures for immigration control and border protection.” This has presented organizations that campaign for development aid and the rights of refugees with a dilemma. Although they try to protect their thematic focus, they are increasingly forced to include migration control in their objectives in order to continue to receive funding.

Strategic outsourcing to third countries

The researcher considers the political pressure to take swift action against irregular immigration to be the reason for the restrictive trend. In this context there is also another trend that Zardo was able to identify: border protection, as well as combating the causes of flight, are increasingly being outsourced to third countries. The impetus for this also came from the member states themselves, who specifically allocated their own national funds to this purpose.

One example of such outsourcing is the EU Trust Fund for Africa. Countries with particularly restrictive immigration policies, such as Hungary or Poland, have contributed heavily to this development fund in order to demonstrate their ability to act and to improve their reputation. Other countries prefer to invest in regions that are geopolitically important to them. France, for instance, focuses heavily on the Sahel, Italy on Libya. Zardo explains: “The kind of investment countries make in external migration agendas is like a compass showing their strategic outlook.”

Turning a few knobs is not enough

This is Zardo’s conclusion so far: “In our project, we were able to demonstrate that the distribution of funding must be analyzed as a political instrument in its own right. We were the first to break down exactly how the use of funds has changed over the last 25 years. This is an important basis for understanding the development of EU migration policy.” As a next step, Zardo and her team plan to conduct interviews with decision-makers. “We want to find out what the reasons for the changes are - whether they are political or bureaucratic.”

Zardo's analyses show that the measures implemented are not always aligned with scientific evidence. “In the past, there has been a tendency to downplay negative evaluations instead of adapting the programs accordingly,” criticizes Zardo. Research demonstrates that the connection between development aid and migration is complex. “While development aid can improve the live of people in third countries, it will not automatically reduce migration to Europe. Likewise, building border fences shifts migration to other routes, which engenders more irregularities and uncertainty. Migration is a human phenomenon that can only be tackled by addressing its entire complexity – not by treating it as a problem that is easy to ‘solve’.”

About the researcher

Federica Zardo is a senior researcher at the Center for Migration and Globalization Research at the Krems University for Continuing Education, where she conducts research at the interface between international relations and public policy, with an empirical focus on the EU's external relations and EU migration policy. Her project “Analyzing change in EU funding for migration and asylum”, receives funding from the Austrian Science Fund FWF under its ESPRIT program, which is designed to foster career development for postdoctoral researchers.

Publication

Tsourdi, L., Zardo, F.: Migration Governance Through Funding: Theoretical, Normative, and Empirical Perspectives, in: Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies 2025

Zardo, F.: Following AENEAS’ Route: Unpacking Two Decades of Migration-Related Measures in EU Development Funds, in: Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies 2025