"We were pioneers"

“I was very surprised and not even aware that I had been nominated”, is how Christoph Hitzenberger recalls the moment when he heard by phone that he had been awarded the Fritz J. and Dolores H. Russ Prize. The deputy head of the Center for Medical Physics and Biomedical Engineering at the Medical University (MedUni) Vienna received the prize earlier this year together with his colleague Adolf Fercher, who passed away just after the award, and three US researchers. With this distinction, also dubbed the “Nobel Prize for Engineering Sciences”, the US National Academy of Engineering (NAE) recognises technological developments which have made “a significant impact on society and have contributed to the advancement of the human condition”.

Revolutionising eye care

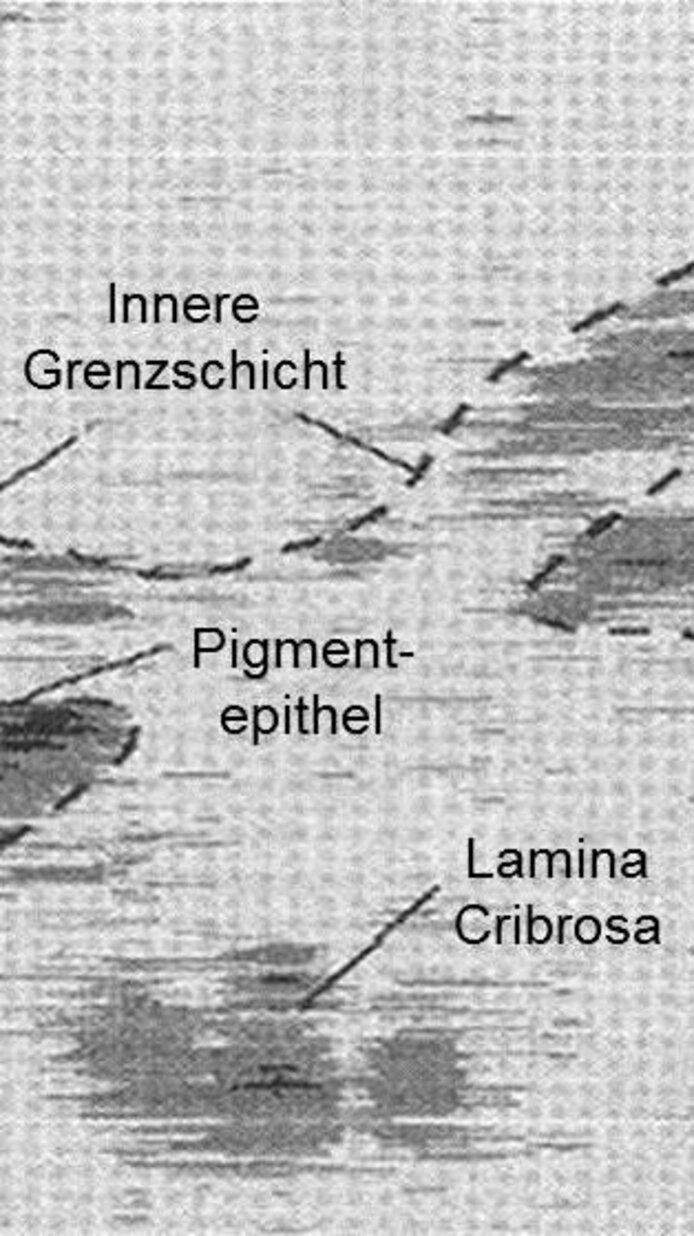

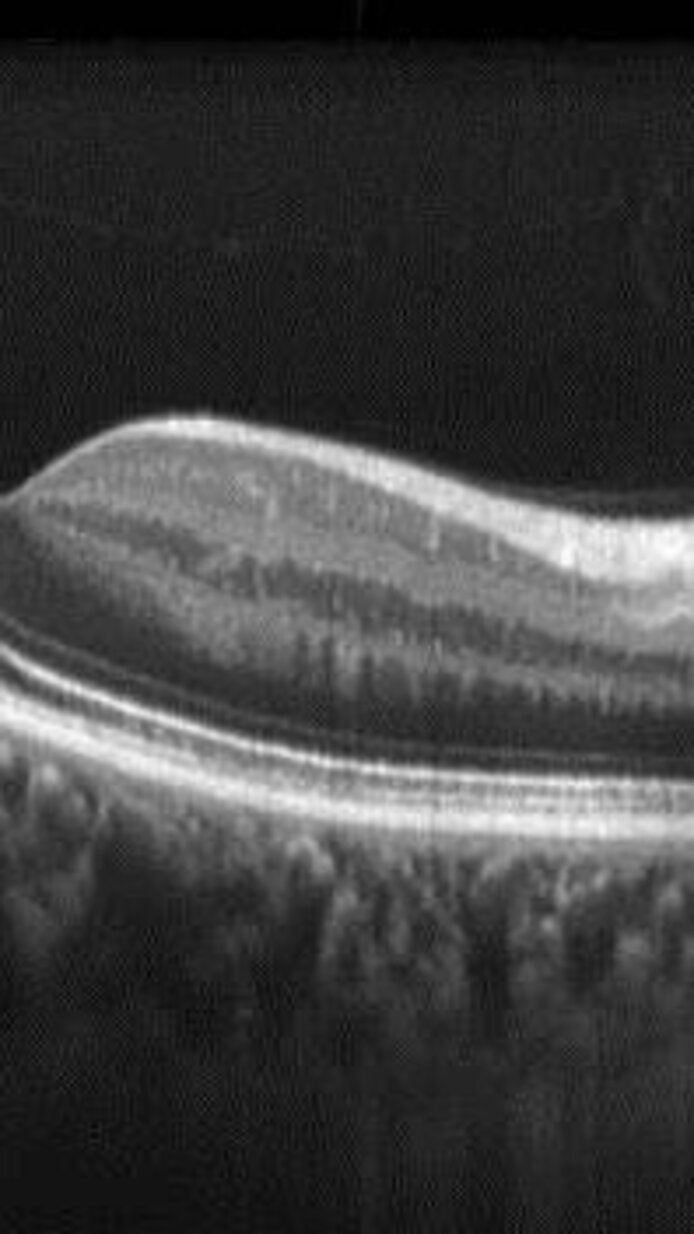

The two researchers from Vienna made vital contributions to the development of optical coherence tomography (OCT), an examination method used mainly in medical imaging. With this technology, even the tiniest changes in the eye’s retina can be made visible. “It revolutionised the diagnosis and monitoring of eye disorders”, says Hitzenberger.

The beginnings

Adolf Fercher and Christoph Hitzenberger were pioneers in this field. In 1986, Adolf Fercher, head of the Medical Physics Institute at MedUni Vienna until 2008, was the first to measure the human eye using ophthalmic laser interferometry. At the time, the measurement required a full 15 minutes. “It was incredibly cumbersome. You had to mechanically adjust the micrometre screws on the interferometer mirror every ten micrometres”, recounts Hitzenberger in recalling the beginnings of their research. In 1987, the newly appointed Professor Adolf Fercher made Hitzenberger his assistant at the Medical Physics Institute. His previous work had been in the field of solid-state physics. “I had no prior experience in this new field, but neither had anyone else at that time”, notes Hitzenberger. “OCT was still a long way down the road, and nobody knew where the developments would go.”

Cataract surgery

In those days, the length of the eye was measured by ultrasound. Such measurements are required for cataract surgery, where the clouded lens is removed and replaced by an artificial lens. In order to avoid patients’ eyesight being defective again after the surgery, their eyes need to be measured with painstaking precision so as to adapt the refractive power of the new lens accordingly. “Ultrasound technology was not really precise enough, and it was pretty inconvenient as well”, notes Hitzenberger.

Development milestones

The interferometry process developed by Fercher was more precise, but its slowness still precluded using it on patients. In 1987, Hitzenberger started work on improving the technique, and the first great breakthrough came in 1990: for the first time, the measurements could be made on patients – but the results were still one-dimensional. The next big step brought two-dimensional images. “In that particular instance, our colleagues at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who shared the Russ Prize, were faster”, recalls Hitzenberger.

Extending the functionality

Today, a three-dimensional measurement of the eye takes between two and three seconds, and the latest prototypes can do it even in fractions of a second. Current research in this field seeks to extend the functionality of the device, providing additionally, for instance, a blood flow measurement. The group led by Christoph Hitzenberger is currently looking at ways of further developing the technique, involving so-called “multi-beam OCT”: this uses multiple instead of only one measuring beam. Combining the signals of these beams in different ways delivers additional information, such as for instance the exact blood flow through the retina. This latest research project exploring this technology is being funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF.

“The prize is also a distinction for the FWF”

This is one of a total of 10 FWF-funded projects in which Hitzenberger has been involved in different capacities – first as a team member and later as principal investigator. “Without the support of the FWF I wouldn’t be where I am today. That is why the prize is also a distinction for the FWF”, emphasises the physicist.

From a family of doctors …

Coming from a family of doctors, Hitzenberger consciously decided to do something completely different. Even at school, he took a particular interest in physics and mathematics. As a young boy, he read biographies of scientists such as Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr. – They were his models. Having attended secondary school with a focus on classical languages instead of science, his subsequent choice of study was unusual, and he had to catch up with a lot of mathematics during his early terms at the University of Vienna.

… via solid-state physics …

Hitzenberger calls to mind a study that says only very few secondary-school leavers with a non-science focus take up a science course of study - but those who do are successful. “I guess the reason is that these students take a genuine interest in their subjects. Without this level of interest you will not go far in studying mathematics or physics”, explains the 59-year-old scientist.

… to the Vienna General Hospital

Hitzenberger is quietly amused about the fact that he decided to do something completely different from most of the other members of his family of doctors, but ultimately landed at the Vienna General Hospital (AKH) after a detour via solid-state physics.

“In Austria, my career is on hold”

After Adolf Fercher became an emeritus professor, the Center for Medical Physics and Biomedical Engineering at MedUni Vienna was created by merging two institutes. Since that time, Hitzenberger has been the deputy head of the Center on Währinger Gürtel in Vienna. “Given that I am not a full professor, my executive authority is restricted”, notes Hitzenberger ruefully. He feels that his career has stagnated since he acquired his venia docendi in 1993. “I sit on international bodies, I am the editor-in-chief of one of the most important journals in my field, I enjoy international recognition – now including the Russ Prize – but in Austria, my career has been on hold for twenty years”, the scientist concludes.

Hierarchical system

Why is that? Christoph Hitzenberger feels the problem has its roots in the hierarchical system at Austrian universities. When he talks to American colleagues, they fail to understand why he is not a full professor. Hitzenberger would like to see a system similar to the US tenure track established in Austria, which gives every academic the chance to gain a long-term professorial appointment after a certain trial period. There is an assessment every few years, and if the result is positive one rises in the system. “I would be a full professor at any American university”, says Hitzenberger.

No reason to go abroad

The physicist thinks the fact that he is not a full professor in Austria has to do with his having chosen not to go abroad for an extended period during his career. There were several reasons for not doing so: “Initially, it wouldn’t have made sense. What I did here I could not have learned anywhere else. We were the pioneers.” Later, there were personal reasons. Being the father of a son he would either have had to leave his family behind, or else his wife would have had to give up her own career, and he was unwilling to accept either of these options. Today, his wife, a physicist like him, is Vice-Rector at the University of Vienna. His son, 27 years old by now, continues the “tradition” of doing something completely different: he is a Japanologist and is studying at the Diplomatic Academy.

Postdocs much in demand abroad

When observing the students at his institute, Christoph Hitzenberger notes that it is difficult to retain good people. The scientist notes that big investments are made in the training of the students; they learn a great deal and then leave, because they fail to see any prospects for themselves in Austria. “The ones who profit are universities and companies abroad. I often get inquiries from American universities that are desperately looking for good postdocs. Our graduates are highly thought of, we have a good reputation.”

Supporting high-risk research

Hitzenberger considers the FWF to be of central importance for his career in science and would like to see the institution getting more money. “The restricted approval rate means that even good projects have to be refused and high-risk projects are not even submitted”, he notes regretfully, quoting his own work as an example: “The activities we started in the 1990s were high-risk projects. Nobody knew where it would all go and whether it would be useful. Today, it probably wouldn’t receive funding.” Hitzenberger goes on to add: “Only if you fund projects like these can you develop the technology of the future. Investing exclusively in projects you already know will work does not lead to scientific breakthroughs!”

Christoph Hitzenberger is the deputy head of the Center for Medical Physics and Biomedical Engineering at the Medical University Vienna. In early 2017, together with his late colleague Adolf Fercher, who died in March 2017, and three US colleagues from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Hitzenberger received the Fritz J. and Dolores H. Russ Prize from the United States National Academy of Engineering (NAE) for the development of optical coherence tomography (OCT). The researcher from Vienna studied physics and mathematics at the University of Vienna and acquired his venia docendi in 1993.