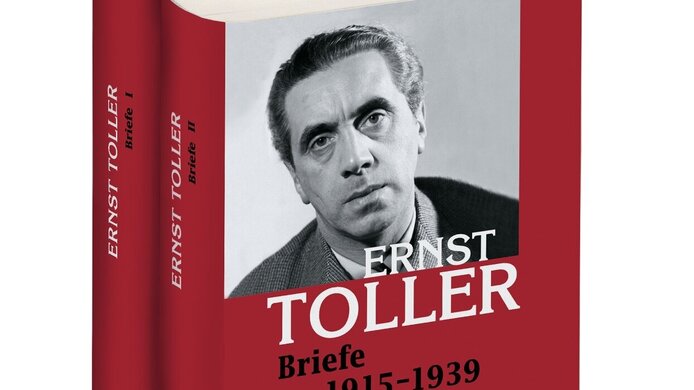

Unconditionally, Ernst Toller

Direct and up-front, that's the German poet and dramatist Ernst Toller (1893-1939). That's how he writes. For instance in New York on 13 May 1939 in a letter to Prince Hubertus zu Löwenstein: "Reliable friends report that the writer Walter Mehring finds himself in wretched circumstances and close to starvation. I don't need to tell you who Walter Mehring is. I hear he is in the running for a scholarship. I recommend him most warmly and with great urgency." This is by no means the only letter from the energetic author and part-time politician in which he speaks out in support of someone else. Under the lead of principal investigator Stefan Neuhaus, Irene Zanol, Gerhard Scholz, Veronika Schuchter and Martin Gerstenbräun from the Innsbruck Toller Research Centre searched hundreds of archives and found 1,665 items of correspondence ranging from letters to field postcards and telegrams. The finds were vetted, edited and commented. Now, the FWF-funded project Commented Edition of Ernst Toller's Letters is ready to go to print.

Congruency between person and author

“In general", says Stefan Neuhaus, a Professor of Literature Studies at the University of Koblenz, "an author and his or her work diverge from one another.“ Here the private individual – there the oeuvre, a staged production. Not only the works, but also what lies between is the object of literary research. According to Neuhaus, Shakespeare is known to have existed as a real person, a human being. Whether he was actually the author of the body of work ascribed to him, on the other hand, is questioned again and again. And there can be no definitive answer to this question.

“It's quite different with Toller”, explains Neuhaus in the interview with scilog. In his case, there is congruency between the private and the public life, the author and the politician. They are as one and, thus, a treasure trove of information for sociologists, contemporary historians, literary scholars and everyone interested in literature. “Diaries and letters", notes Neuhaus, “are indispensable for understanding the period.” Toller's documents stand out and provide a unique insight into the social history of the Weimar Republic and the situation of a person in exile.

Years of frantic activity

Toller was a live wire. In 1918/19, he played a central role in the short-lived Bavarian Soviet Republic, “when the poets took power" (the eponymous book by Volker Weidermann was published by Kiepenheuer & Witsch). As a communist and Jew, as a “red”, Toller, like others, was threatened with the death penalty when summoned before a court martial. But he was saved by his reputation as a writer and the advocacy of his teacher Max Weber, who called him a man of ethics. The death sentence was substituted by five years in prison. He refused to be released ahead of time (again on account of his literary work) unless all fellow prisoners benefited from the same amnesty - he remained in prison. He left Germany in 1932, just in time. The following year, his works were banned and burned in the Nazi Reich. Toller never stopped writing. And he kept corresponding: with W. H. Auden, Albert Einstein, Hermann Hesse, Egon Erwin Kisch, Karl Kraus, Klaus and Thomas Mann, with Erich Mühsam and Franklin D. Roosevelt, Jawaharlal Nehru and Leon Trotsky. And that is just a small selection, an inkling at best.

Free of ballast

“A new take on Toller has emerged", says Neuhaus, who also supervised the critical edition of Toller’s work (Kritische Ausgabe der Werke Ernst Tollers). "I have come to know Toller in his unconditionality." As a literary, not just political author. As someone who never stopped speaking up for others. For Carl von Ossietzky, Walter Mehring, for all those who needed his support. Or might have needed it. His writing is straightforward, precise and ballast-free. According to Stefan Neuhaus, his letters became more confident and clearer over time. On 22 May 1939, Toller committed suicide. "A rash act", Neuhaus is convinced. One that can't be explained by his letters.

Personal details Stefan Neuhaus began his career as a research assistant, visiting professor and professor at the Otto-Friedrich-Universität Bamberg. His work then took him to the University of the South (USA), the University of Innsbruck and the University of Oldenburg. He has held a professor’s post at the University of Koblenz-Landau since 2012.

Publications