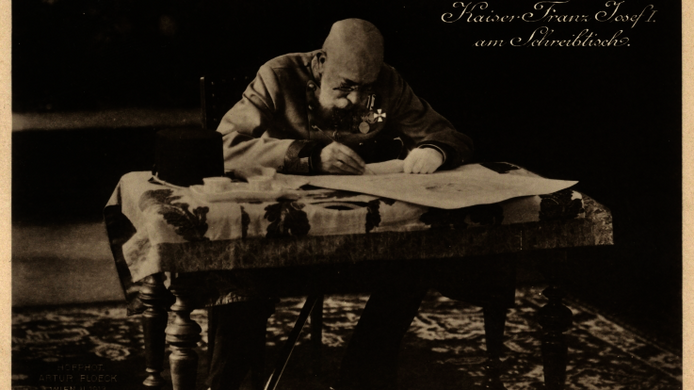

The Emperor’s desk: the decisions of Emperor Francis Joseph I

If pieces of furniture could speak, the desk of Emperor Francis Joseph I (1830-1916) would fill whole volumes. This was the place where he took decisions every day, from the very small to the very weighty, and he fulfilled his role as a final decision-maker from the first to the last day of his reign. It is surprising to learn of his pronounced predilection for consensus, which even suggests commonalities with contemporary politicians. Moreover, the range of issues that needed to be decided was complex and included everything from requests for pension increases, to infrastructure investments and revoking death sentences. “There was a colourful mix of topics ending up on his desk. A small donation of a mere 50 Kreutzer for a public servant may well have been followed by a railway concession. We were fascinated by how little coherence there was in the sequence in which they were dealt with. He must have found that incredibly exhausting,” says Peter Becker, a historian at the University of Vienna. In 68 years of reign (1848-1916), a corpus of 250,000 written submissions (Vorträge) was accumulated, which were filed by the Cabinet Office and are kept at the Austrian State Archives in Vienna.

Decision-making processes open to analysis for the first time

Despite countless publications on the Habsburgs, this corpus had never been systematically researched. The historian Jana Osterkamp from the Collegium Carolinum in Munich knows why: “The corpus served as a kind of quarry for other research questions, because this enormous volume could not be handled with the usual research methods.” The submissions were, by no means, concise notes but consisted in 3-5 page summaries of a particular topic including a draft proposal for a decision by the ministers responsible. They were drawn up by the Cabinet office. Adolf Braun, the director of the Cabinet Office from 1865 to 1899, was considered a close confidant of the emperor. The submissions are therefore a central source for understanding the Emperor’s decision-making processes and they help to answer a number of questions: what ended up on the desk? What policy areas were important and when? How did he decide, and how quickly? Who were the protagonists involved? In an ongoing research project led by the principal investigators Peter Becker and Jana Osterkamp which is funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF and the German Research Foundation DFG, the two researchers are getting to the bottom of this issue. Together with their teams they have developed a new methodology for this purpose. More than 60 percent of a 30 percent sample of the submissions have now been analysed. “By means of the historical-statistical policy field analysis, we can evaluate the Cabinet Office's records statistically and qualitatively. In the process, we are considering not only the content but also temporal aspects such as the time needed for processing,” explains Osterkamp.

Vast number of individual decisions

“It is fascinating, for instance, that the Emperor always showed a strong predilection for consensus. When looking for a comparison with contemporary policy-makers we found that, in this respect, he could be seen as the male counterpart of Angela Merkel,” says Peter Becker, “while the German Emperor Wilhelm II reminds us of Donald Trump.” Although the Austrian Emperor stuck to this leaning towards consensus even in times of dissent, the consensus was negotiated within a small group of political players. “In times of mass politics and, specifically, when conflicts between nationalities arose, this was not an appropriate policy instrument,” Becker adds. Each of the 250,000 submissions is assigned to one of eight policy fields, which the researchers distilled from 30 categories. The Emperor's reign involved traditional areas such as conferring nobility titles, as well as modern policy areas such as the development of railways. Another new aspect concerns an assessment of the decision-making processes over time or according to the type of regulation (law bill, ordinance, individual case decision). “More than 90 percent are individual case decisions, a percentage that blew our minds. Today, many of these things would be part of the micro-management of institutions,” Becker emphasises.

Efficient bureaucracy obscured the holistic view

But who had an impact on the decision-making processes? In order to find out, the research teams are investigating examples from the policy areas of ennoblement practices and railways. One case focuses on the location for the railway station in Lviv, Galicia. “In this case we trace the individual steps of decision making, because it is easier to understand the motivation of the actors involved at the local level than by means of a three-page summary,” explains Osterkamp. Becker adds that in railway projects the stakeholders “appear in the records in the context of the formal processes, for example via petitions or audiences.” Who exerted influence and in what way depended on whether the Emperor decided alone – as in the case of the conferring of titles – or whether ministers were involved. Only in the area of symbolic politics did high-ranking members of society try to peddle influence informally through the Director of the Cabinet Office Adolf Braun. Braun’s legacy is now also being analysed in a case study. The analyses show that Emperor Francis Joseph I relied primarily on administration and specialist bureaucracy and felt it was important to adhere to formal procedures. “He was a highly efficient bureaucrat who did not procrastinate or leave things until later. He took 68 percent of decisions within a day and most of them were completed within a week,” Becker emphasises. This said, the Emperor’s insistence on having the final say, the increase in state tasks and the extremely high proportion of individual case decisions increasingly brought him to his limits. Busily ticking off agendas also had a negative side: it prevented him from seeing the big picture. For major social changes or the advent of modernity rarely or never ended up on the Emperor's desk.

Personal details Peter Becker is a historian and, as of 2014, professor of Austrian history in the 19th and 20th centuries at the Department of History at the University of Vienna. Prior to this, his academic career took him to Italy, Germany and the USA. One of his main research topics is decision-making processes in the development of modern nation states. Since 2018 he has been co-leading the project “The Emperor's Desk: a Site of Policy-Making in the Habsburg Empire” together with Jana Osterkamp. The project is funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF and the German Research Foundation DFG. Jana Osterkamp is a historian at the Collegium Carolinum in Munich. Her main research interests include the history of federalism and the Habsburg monarchy in the 19th century.

Publications