Strategy and focus

For years, efforts have been made in Austria to lure more women into technical professions. But despite these efforts not even a quarter of the students who complete a degree course in a STEM field (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) are women. When investigating causes, it was long thought that inadequate gender equality and a lack of equal opportunities were to blame.

Many female engineers in Southern Europe

However, an international study from 2018 shows that the opposite is true: in countries with less equality, the number of women studying science and technology subjects is actually higher on average. This is an observation that Ioanna Giouroudi, an electrical engineer working at TU Wien, can confirm: “I know many women in Greece, Portugal and Spain who hold important positions in industry.” On the other hand, the current statistics for her field of study – electrical engineering – at TU Wien paint a bleak picture: “The women’s share among students is 13 percent, dropping to 11.2 percent among female graduates and 11 percent among academic staff. And only one of the 20 professorial chairs at our faculty is held by a woman,” notes Brigitte Ratzer, a technical chemist and head of the Centre for the Promotion of Women and Gender Studies at TU Wien.

“Gender-equality paradox”

In countries such as Albania, Algeria, Tunisia and the United Arab Emirates, up to 40 percent of the relevant STEM degrees are awarded to women. In Norway and Finland, on the other hand, the figure is only 20 per cent, although these two countries, according to the Global Gender Gap Index, are right at the top in terms of equality, whereas the Arabic-speaking countries mentioned above are far behind . Experts had initially assumed that the differences in the career choices of boys and girls would disappear with an increase of equal opportunities in a society. But apparently the opposite is the case – a situation that in technical jargon is referred to as the “gender-equality paradox”.

Engineering professions offer better career opportunities

The authors of the study mentioned above, Gijsbert Stoet and David C. Geary, analysed over 400,000 young people aged between 15 and 16 from more than 50 countries. The picture that emerged was that there were no significant performance differences between male and female students in science and mathematics. When it came to the personal "strongest subject", however, boys did better in the natural sciences, whilst girls did better in reading. This personal “strongest subject” could be one explanation for the professional choices made by girls. The two researchers say that people living in countries with more equal rights, good social security and generally a high level of life satisfaction have the corresponding freedom to decide according to their aptitude and preferences. On the other hand, a lower degree of social security and poorer prospects could be reasons why more girls pursue a scientific career in countries with less gender-equality. They expect this choice to increase their chances of a secure job and a good income.

Looking for a job with good prospects ...

Ioanna Giouroudi, who grew up in Greece, can confirm this outcome of the study: “In my home country, personal inclination was never the only guideline in choosing a career, but there was always the question of what holds out good future prospects and where you can earn a good income. The fact that engineering is not globally the preserve of men is also corroborated by a figure provided by Brigitte Ratzer: “40 percent of female students at TU Wien do not come from Austria, but from Southern Europe, Eastern Europe, Arab states, Turkey and Iran.”

... instead of becoming a PE teacher

If Ioanna Giouroudi had been able to decide regardless of economic considerations, she might have become a PE teacher, as she notes with a smile. Not an improbable choice, since she was a sports enthusiast already as a child, pursuing track and field sports, basketball and tennis.

Playing chess with a rapier

By the age of 13 she was on her way to becoming a professional fencer. A trainer recognized her talent and, after only three months of coaching, she took part in competitions winning medals in Greece, Austria and South Africa. The particular fascination this sport holds for her is the combination of strategic knowledge, technique and focus. “Every opponent is different, you have to identify their strategy within the first few seconds and choose your own accordingly. It's like playing chess,” she says enthusiastically. However, her part-time fencing career ended in 2010 since the strain on her joints became too great. “If I had gone into it professionally, I would have had more time for physical regeneration,” she notes and explains that the sport has too little broad-scale impact to be able to make a living from it. “It’s easier with a sport like basketball. In fencing, as in tennis, you really have to be at the top to make a living.”

Family missions with a cordless screwdriver

Nonetheless, studying electrical engineering was not a purely rational decision, as the now 40-year-old had taken a lively interest in technology from childhood and always assisted her parents when something needed to be repaired or installed. Even today, she is the one who steps up with a cordless screwdriver and electric drill whenever there is a “construction site” in the family.

From Greece to Vienna

During the time she was preparing her diploma thesis at the National Technical University in Athens, the young scientist began to work on magnetism and finally decided to switch to TU Wien in Vienna. It was here that she conducted her first project funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF, a cooperation with Siemens Erlangen. “That was exactly what I wanted to do: develop magnetic materials for sensor applications,” she recalls. In the following three years Giouroudi partly divided her time between a Marie Curie position and her doctoral thesis.

Experience in the automotive industry

This research- and labour-intensive period was followed by work in industry. In 2006/2007 she was a project manager at Magna Steyr. A valuable experience for her, as she learned about a world that seems so very different from research: “In industry, you have to accept

assignments where you don't know if you can get them done in time, just so as not to lose the contract to the competition. No-one asks whether we can manage it on time, whether it interferes with other projects and how much manpower we need. This enormous pressure also creates an uncomfortably tense atmosphere. There is a lot of pressure in the world of research too, sometimes the very existence of a group may be at stake, but we do try to find a common solution and the atmosphere remains friendly,” is the comparison she draws. Giouroudi is grateful for this experience nevertheless, as it taught her how to communicate properly with industry, a necessary partner for her projects.

Portable sensor for water quality analysis

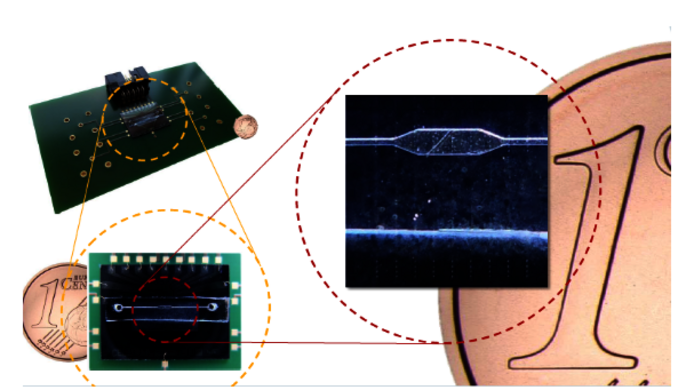

During her postdoc stay at Stellenbosch University in South Africa in 2007, Giouroudi’s work focus shifted to the area she is still most interested in today: medical technology. In the context of two FWF-funded research projects completed in 2017, she developed a new biosensor to screen water and other fluids such as milk and juices for pathogens. The biosensor is based on magnetic nanoparticles. In terms of application, the idea is for example to check the water in rivers, wells or swimming pools for pathogens on site. All you need is a laptop and a sensor that is no bigger than a small smartphone, all electronics included. “This is a field of research with enormous potential that people are working on intensively the world over,” says Giouroudi. Areas of application include the food industry or blood sampling.

Application for blood tests researched

It would still take several years of intensive research to make the sensor she developed usable additionally in blood tests. If, when an accident occurs, it were possible to test blood in the ambulance rather than wait for the laboratory, this would save an enormous amount of time and money, and, in many countries where there are simply not that many laboratories, it would even constitute the possibility of doing a test in the first place. “There is intensive work going on in this field worldwide. Portable devices do not yet deliver the level of accuracy of a laboratory, which is why products often fail to make it to the marketplace,” says the researcher in explaining the challenges involved.

Encumbered by “chain of contracts” rules

Giouroudi herself, however, will not be working on her sensor in the next few years because of the provision applying to so-called “chains of contracts”. Her contract with TU Wien expired in July 2017. Originally introduced to protect employees, this provision stipulates that university staff employed in the field of teaching or through third-party funding and research projects may not be employed for more than six to eight years on fixed-term contracts. The underlying rationale was actually benevolent, since the provision was intended to ensure that, after several years of working under fixed-term contracts, a researcher should be awarded a permanent position. In practice, however, what happens is the exact opposite. Universities seldom award indefinite contracts, which means that many researchers see their university careers end for good at the end of their six-year fixed-term stint.

Coordinator of the TU Doctoral School

Ioanna Giouroudi was lucky, though. She is staying on at the university as the coordinator of the TU Doctoral School, a position she moved to in October this year. Although no longer an active researcher herself, she remains in the science environment and can contribute her scientific experience. Her task is to coordinate doctoral training under one roof. “For doctoral students, this has the benefit of making their training more structured. In addition, we try to provide the young people with enough funding for them to be able to concentrate entirely on their research,” says Giouroudi in pointing out two important goals. Her networking function will require a lot of communication. Her open and friendly personality will be a great asset there – together with the fact that she has been with the institution for many years and knows most of the long-serving staff.

Strategy and focus

It is a challenging job, but one that is more compatible with her private life. Challenges are waiting there as well: her two-year-old daughter was joined by twin siblings a year ago. And here, too, the skills perfected in fencing are helpful: strategy and focus. She keeps her cool and was not even rattled when she was asked solicitously by a female bureaucrat whether she had really thought long and hard about whether she wanted to go on working with three children at home.

Personal details

Ioanna Giouroudi started coordinating the TU Doctoral School at the Vienna University of Technology as of October 2019. She studied electrical engineering in Chalkida, Greece, and received her doctorate in Vienna. After working as a project manager for Magna Steyr for six months in 2006/2007, she spent a postdoctoral research period at Stellenbosch University in South Africa, where she began her work in medical technology.

From 2009 she was a university assistant at the Institute for Sensor and Actuator Systems of TU Wien, acquired the venia docendi at the University of Natural Resources and Applied Life Sciences Vienna and was Senior Scientist at the Institute for Sensor and Actuator Systems of TU Wien until July 2017. Giouroudi worked on the development of biomedical, portable diagnostic systems that could be used away from a laboratory. In 2017, with the help of FWF funding, she succeeded in developing a portable sensor that detects pathogens in water.