Migration and border security in the Habsburg Empire

The protection of external borders and control of migratory movements are not only a matter of concern for today's governments, they were also a preoccupation of the Habsburg Empire's authorities in the 18th century. As part of a project funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF, historian Josef Ehmer from the University of Vienna and his colleague Jovan Pešalj have studied the development of the Habsburg Empire's initial measures for controlling migration at the border to the Ottoman Empire and emphasize the pioneering nature of this policy: "Responsibility for border security and the control of migrant mobility was shifted from the regional level to the central state level and systematised. These measures in the Habsburg Empire anticipated the nation-state practices of the 19th century as implemented by France, for example."

First modern border

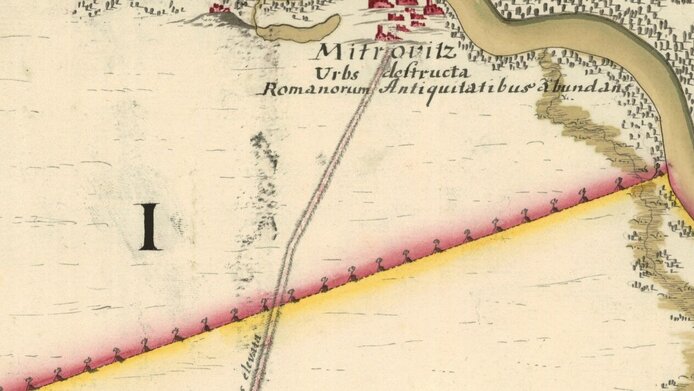

The project explains the development of the borders between the Habsburg and Ottoman Empires. Ehmer and his research team set out to answer the question as to why the first modern border arose in this economically peripheral location and found the answer in a series of overlapping military, medical and economic factors. Thanks to its clarification of territorial claims, the Belgrade peace settlement between Vienna and Constantinople resulted in the modification of the military border in 1739 and the erection of a permanent cordon sanitaire. This enabled the establishment of a stable border between the Ottoman and Habsburg Empires and the mobility control of Ottoman migrants.

Strict border controls

With the help of records from the quarantine stations at the cordon sanitaire, the research team analysed the development of a systematic system of immigration and import controls. "The erection of a permanent cordon sanitaire included strict border controls at the fortified military border," explains Ehmer. "In addition to continuously manned watchtowers, which maintained visual contact with each other, border points with quarantine stations were built. Records were kept on persons entering and leaving the territory for the Health Commission and the Austrian royal registry." A medium-sized quarantine station, like that of Mehadia in Banat (today’s southwestern Romania), received an average of 516 people annually and consisted of 26 units which included quarantine residences, offices, store rooms, stables and an inn. The border-crossing system was strict: "Travellers were detained for at least two to three weeks and for several weeks in the event of a plague risk. Their clothing and any goods and objects they were carrying were washed and fumigated to eliminate toxic vapours (miasmas) that were suspected of harbouring plague pathogens. Accompanying animals were taken to nearby rivers for cleaning," says the historian, explaining the epidemiological measures implemented at the time. "In addition to health concerns, there were also economic reasons for controlling people entering the territory: many Ottomans were traders and brought raw materials like wool and leather and food into the country, for which customs duties had to be paid."

Travel documents for mobility control

As the project's findings show, the Habsburg central authorities' access to information about people entering the Empire was facilitated by the monitoring of their settlement and mobility within the territory. The development of travel documents like passports and other means of identification can be seen as the first modern forms of mobility control, while the methods employed, however, were still far from uniform in the 18th century. In addition to the travellers' names, information was also generally recorded at the border controls to the Ottoman Empire about their origins, profession, ethnicity and religious affiliation. On the payment of a stamp fee, the travellers were issued with passports by the border authorities, which they were required to carry with them at all times.

Immigration and demographic policy

Based on naturalisation regulations, the research team also examined the significance of all of these controls and data records for the Habsburg population policy. "The population policy of the time was strongly oriented towards growth so immigrants were basically seen as an asset. At the same time, however, the relationship with migrants was ambivalent," explains Ehmer. "In the case of Ottoman immigrants who wished to settle permanently in the Habsburg Empire, it was deemed necessary to eliminate as far as possible any doubts about their loyalty to the Emperor." The FWF project shows how a state-wide migration policy arose in the case of the Habsburg Empire of the 18th century. Its findings may contribute to the differentiation of contemporary political-social discourse on population policy and migration control.

Personal details Josef Ehmer is Emeritus Professor of Economic and Social History at the University of Vienna and Associate Fellow at the International Research Center "Work and Human Lifecycle in Global History" at the Humboldt Universität zu Berlin. His research focuses on the comparative social history of Europe from the 18th to 20th centuries, in particular the history of the family, workers and artisans, migration, ageing, population history and historical demography. Jovan Pešalj is a research associate at the University of Vienna and a PhD student at the University of Leiten. His research focuses on the social history of central and south-east Europe in the early modern period and the history of modern nationalism.