Civil servants: serving and supporting the state

Although one inescapably has to deal with civil servants when coming into contact with the Austrian state bureaucracy, the notion of a public servant whose service and loyalty are rewarded by a secure post and lifelong provision is no longer quite so inescapable. In historical terms, the concept is relatively young. It was at the end of the 18th century that Emperor Joseph II introduced this form of civil service, based on the ideal of a servant of the state who is immune to bribery and always correct in the execution of his function.

“This is still one of the few positive stereotypes relating to civil servants,” says Therese Garstenauer of the University of Vienna. In her FWF-funded project she is addressing a research gap: a great deal is known about the overblown civil service system of the Habsburg monarchy, plenty is known about the precision of the Nazi regime’s administrative apparatus, but the years between the two had received little attention so far.

From crown to crisis

During the Austro-Hungarian monarchy and beyond, civil servants were an important section of the population. According to contemporary estimates, the early 1920s saw about one-seventh of the population dependent on state employment, be it in active service, in retirement or as a dependent of a civil servant. “It is no coincidence that people say that the civil service left its stamp on Austria,” says Garstenauer when talking about its historical roots.

The system was hit all the more drastically, when almost a third of civil servant posts were abolished between 1922 and 1925. This cutback had been stipulated by the League of Nations as a precondition for economic aid. “In retrospect, however, the savings were not great, because the system did not really change that much,” notes Garstenauer. Retired civil servants still had to be paid and some posts were filled again a short time later. At the same time, civil servants who kept their posts were affected by the hyperinflation that peaked in 1922. The value of their fixed salaries was almost completely obliterated within a short time.

Dignified demeanour in hard times

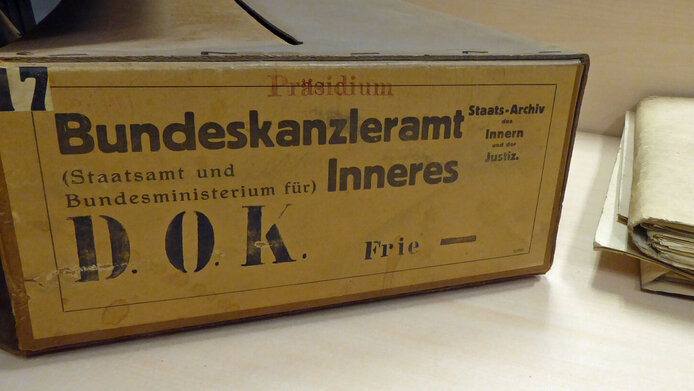

In her work, Therese Garstenauer is particularly interested in the effects of crises that brought fears of losing status. What happens when this kind of middle-class section of the population feels hard done by because what they believed to be inexorable conditions of life were not fulfilled? An essential source of information for the historian’s project are thousands of files on disciplinary proceedings against civil servants from the most diverse fields. Their private conduct also played a role, since civil service law stipulated that a civil servant had to lead a life “befitting his status” at all times. This refers not only to a certain material living standard, but also to the fact that a civil servant must behave at all times in a manner that does not detract from the dignity of the office. If civil servants behaved in a disorderly manner in a pub under the influence of alcohol, or had extramarital affairs, or were massively in debt, they had a problem under civil service law. The documented proceedings also illustrate the difficult economic situation of the 1920s, even among civil servants with secure jobs.

Garstenauer recounts the example of a postal worker who took home some yeast for baking bread from a package damaged in transit because many staple foods were in short supply. A typical offence was opening letters from abroad in the hope of finding foreign currency in them that would withstand inflation. But she also found somewhat more absurd stories, such as the case of a high-ranking civil servant who stole a fur hat that the wind had blown away after a storm had broken a shop window.

Some are or become more equal

Punishment for these offences – pay cuts, demotions, dismissals – varied greatly according to the type of offence and the respective individual. “It is noticeable that very little happened to senior officials, and sometimes no proceedings were opened at all,” says Garstenauer, who believes that people hastened to find mitigating circumstances in the case of senior civil servants, who often got off with a mere caution. Moreover, the files tend to contain less information about the person's life and background if the accused was a high-ranking official.

The 1930s saw an increasing number of disciplinary proceedings for political offences. As a result of the putsch of the paramilitary Heimwehr in September 1931 and even more so during the Corporate State (Ständestaat), civil servants were banned from any political activity. It was even considered political activity if someone merely had a leaflet in their pocket or said nothing when a colleague discussed politics in the pub. In the course of the 1930s, society, and with it the civil service, became more and more radicalised.

Women in state service

There were also women working in the civil service – although for most of the time they tended to work on the basis of normal contracts rather than as tenured civil servants. In the main, women worked in the lower-paid clerical service. The few who reached higher positions worked in the fields of education and social affairs. Until 1919, female civil servants were subject to a celibacy requirement, meaning that only single and childless women could work in the civil service. Some Austrian provinces maintained this regulation until the 1930s.

Many women were then affected by the “double-earner regulation”, which was designed to keep jobs for as many men as possible in times of high unemployment. Women in the civil service who were married to a civil servant had to resign from their post if the husband’s salary reached a certain limit. The regulation contained a reference to unmarried cohabitation that feels quite modern – anyone who tried to circumvent the regulation in this way was also committing an official offence.

Even though the regulation seems very unfair, it did not lead to mass dismissals of women teachers or typists, but affected only individual posts in various fields. One may therefore doubt whether it achieved the intended benefit of reducing male unemployment. This and other civil service regulations illustrate, however, what society considered a respectable life befitting the status of a civil-servant.

Personal details

Therese Garstenauer studied history, sociology and Russian in Vienna, Moscow and Edinburgh and completed her doctorate at the University of Vienna on cooperation projects between Russian and Western gender researchers. She first came across civil servants as a research subject in a research project of the Austrian Historical Commission on the confiscation of property during the Nazi era. After participating in a research project on corporate communication in Russia at the Vienna University of Economics and Business Administration, she was awarded the Elise Richter Fellowship of the Austrian Science Fund FWF in 2016 for her professorial qualification project on civil service in the interwar period.

For more information on the project see her blog (in German): Österreichische Staatsbedienstete und standesgemäße Lebensführung