Transatlantic musical crosscurrents

Around 1800, a rich musical tradition was nurtured at royal courts, monasteries, conservatories, theaters and even the first concert halls in Europe. In the newly established United States of America, similar cultural spaces for musical exchange and encounter were still few and far between. Most opera houses, concert halls and similar institutions across the ocean were only established after the end of the War of Succession in 1865. New York’s world-famous Carnegie Hall, for instance, celebrated its opening night in 1891. Nevertheless, vibrant musical practices were found in the New World already before that. Musicians, sheet music, music-related expertise and instruments crossed the Atlantic and merged into a musical culture that was both similar to and also strikingly different from Europe’s traditions.

In the project “Musical Crossroads. Transatlantic Cultural Exchange 1800–1950”, which was financed by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), musicologists studied this “pre-institutional” phase of music history in the United States. “As part of this project, we also explored the question how music could be moved and transported before modern recording and storage technologies were invented and in which ways the encounter of different cultures changed it,” the project’s lead researcher Melanie Unseld of the University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna sheds light on the background of her research. Together with her colleagues Clemens Kreutzfeldt and Carola Bebermeier, she investigated the trade of music-related goods and music salons in the USA as two examples of spaces that clearly depict the transatlantic music transfer at the time. In doing so, the team has put the spotlight on a topic that has hardly been touched by research so far.

The nodes within the musical network

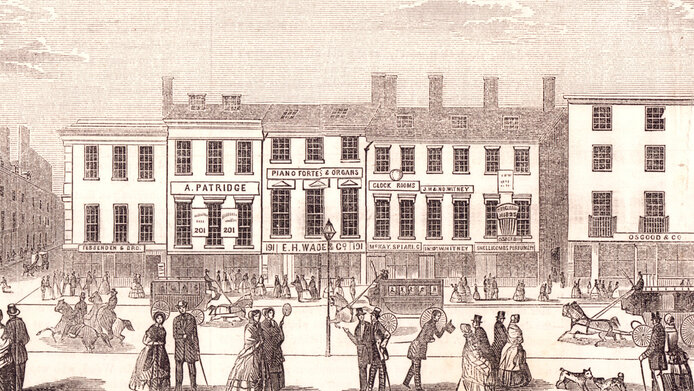

“Music shops were multi-functional places, serving as hubs of exchange for anyone and anything that had to do with music in an American city. They were places where musicians met and networked and also played concerts,” Unseld explains. The bourgeois salons, on the other hand, were also devoted to demonstrating manners. “They were spaces where one could practice ways to communicate and interact in a fashion that was deemed civilized. And music played a significant role in this context,” the researcher says. The team not only investigated these spaces as venues where music was performed but also engaged in a “sociology of space” and looked at them as critical points in a social network that was constituted through communication and interaction.

The researchers used a wide variety of sources for their project. “These included the estates of deceased people, travel logs, historical newspaper articles and pictures, advertisements and collections of sheet music, much of which we accessed from US archives,” Unseld lists the material. “For instance, there was a journal by an American musical goods dealer on a shopping trip across European capitals that showed us in detail which instruments and sheet music he expected to go fast at home.” The project is, inter alia, based on the concept of a cultural transfer. Unseld comments: “This approach posits that the mobility of people or things across cultural borders also changes the culture of origin – which is why we were also interested in the New World’s influence on music culture in Europe.”

Trade as a form of music education

In his field of focus, Clemens Kreutzfeldt was able to highlight the immense influence of traders of music-related products as cultural brokers of music culture in the 19th century. On top of providing access to sheet music and instruments from across the Atlantic, they also imported expertise and contextual knowledge. “The traders translated European ideas for American society,” Unseld explains. “They did not only provide the sheet music but also conceptions of what a piece should sound like.”

When the music was adapted for the new audiences, time and again things were attributed to wrong sources. “Such erroneous statements were not only made about purported composers but about whole genres and styles; and one reason for the fibbing was marketing,” the musicologist specifies. “A piece presented as a Styrian Landler in the US was very likely neither a Landler nor of Styrian origin but an imagination of Styrian music conceived of in the New World.” At the same time, European musicians went on concert tours across the USA from an early stage, their main objective being to boost their careers back home in Europe: for them too, the traders were important points of contact.

The salon as a place to practice manners

Carola Bebermeier’s research produced the surprising result that US salon culture likely originated in the Southern states, from where it spread to the American Northeast. She found that a lively salon culture with music performances as a core element was already a fixture in the Southern states in the mid-19th century. “Collections of sheet music tell us, for instance, that in the Southern states, with their history of European colonization, French and Italian music, and here especially operas, were held in high esteem in addition to parlor songs, which were popular across the entire country,” Unseld explains.

The investigation of the “parlors”, as the bourgeois salons in the USA were referred to, also revealed that even though American society was highly critical of aristocratic systems in political terms, European behavior manuals, which were strongly influenced by noble families, were very much en vogue. “In America’s society of the time, the divides between social strata were marked by behaviors and identity constructions that were acquired in the parlors,” Unseld holds. In the 20th century, the salons in the homes of the American bourgeois also became a place where exiled Europeans came together to keep alive the memories of their lost home countries. Thanks to a follow-up project organized in the framework of the FWF’s Elise Richter Programme, Carola Bebermeier will be able to continue her work on US parlor culture.

Publications

Bebermeier C., Kreutzfeldt C., Unseld M. (eds.): Music Across the Ocean: Processes of Cultural Exchange in a Transatlantic Space, 1800–1950 (vernetzen – bewegen – verorten. Kulturhistorische Perspektiven series), Bielefeld: transcript, in print

Carola Bebermeier: “Sundays at Salka’s” – Salka Viertel’s Los Angeles Salon as a Space of (Music-)Cultural Translation, in: Musicologia Austriaca: Journal for Austrian Music Studies, June 2021

Carola Bebermeier: The Arensberg Salon in Visual Representation. Chez Arensberg by André Raffray and the Historiography of Dada, in: Music in Art XLV/1-2 2020

Carola Bebermeier and Clemens Kreutzfeldt: Musical Crossroads. Europäisch-amerikanischer Kulturaustausch in vorinstitutionellen Räumen Bostons des 19. Jahrhunderts, in: Klingende Innenräume. Gender Perspektiven auf eine ästhetische und soziale Praxis im Privaten, Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann 2020

Personal details

Melanie Unseld is a Professor for Historical Musicology and heads the Department of Musicology and Performance Studies at the University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna. She previously worked at the University of Oldenburg and the State College of Music and Drama Hanover. The project “Musical Crossroads. Transatlantic Cultural Exchange 1800–1950” received funding by the Austrian Science Fund FWF in the amount of EUR 359,000.