When fashion violates (Soviet) standards

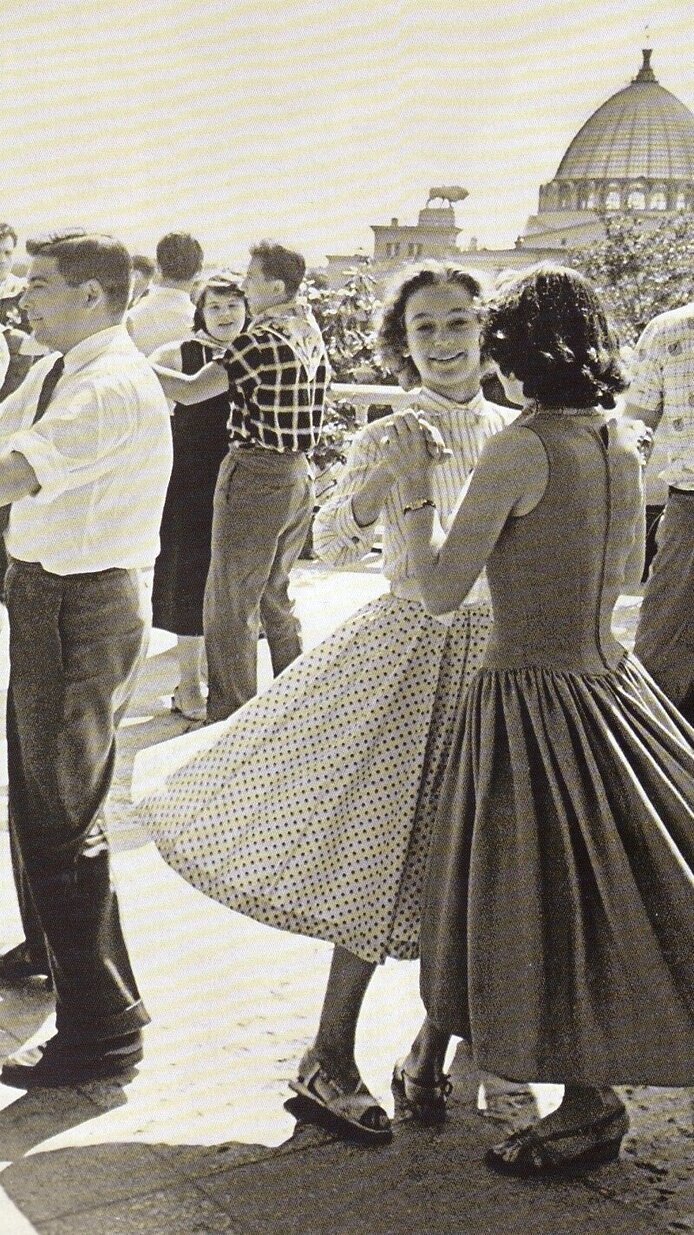

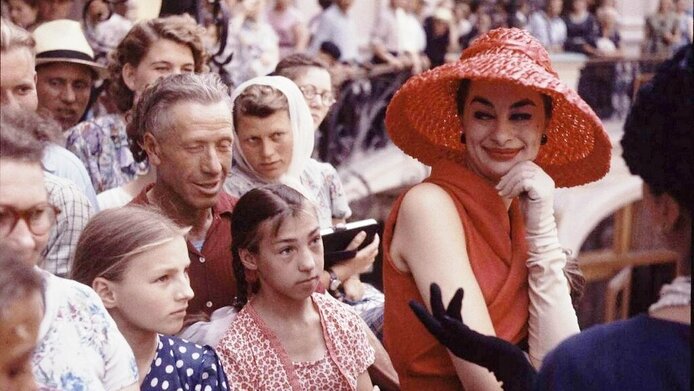

Strolling through the streets of Moscow in June 1959 one might have witnessed unusual scenes. Upbeat French models in colourful, extravagant – yet wearable – dresses were walking around the city. Under the astonished gaze of the ordinary people in the street, the models posed with sailors and in front of tourist attractions. It was all in preparation for a five-day Dior fashion show. While the fashion label created its “New Look” under its new creative figurehead Yves Saint Laurent, a transformation was under way behind the Iron Curtain overlooked by many, first under the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev and then under Leonid Brezhnev. Politicians and members of the country’s “elite” engaged in a vibrant exchange with western celebrities, like the well-known French couturiers. Russian stars such as the legendary ballet dancer Maja Plisetskaya brought Western clothing style as found in the designs of Pierre Cardin and Coco Chanel to the East and thus ushered it into Soviet everyday culture.

Fashion as a mirror of everyday culture

There were differing routes for the Western influence on Soviet fashion, notes Eva Hausbacher from the University of Salzburg in the interview with scilog. “Russian delegations attending trade fairs and exhibitions abroad - and also members of the upper class - were the official route, because they were allowed to travel. Exchanges within the Soviet satellite states also played an important role. And then there was the black market, where, for instance, Burda magazines were bought and sold.” Together with Elena Huber and Julia Hargaßner, this Slavonic scholar investigated fashion starting from the political “thaw” after the death of Stalin in 1953, through the stagnation period of the Brezhnev regime until the beginning of perestroika in 1985. Behind the Iron Curtain an everyday culture started to develop which, not entirely unlike its equivalent in the West, focused on individuality, emancipation and progress. – That is the central conclusion of this FWF-supported research project.

The research was conducted in two sub-projects. “Clothing Language in Artistic Text” explored the topic on the basis of literary texts and films. “Tailor-made Self-modelling” focused on an analysis of fashion and women’s magazines, self-help books and theoretical works on fashion and consumption. In the process, the cultural scientists uncovered everyday practices demonstrating a change of values in Soviet society, “which paved the way for the dramatic social and economic changes brought about by the perestroika era”, explains principal investigator Eva Hausbacher.

Do-it-yourself emancipation

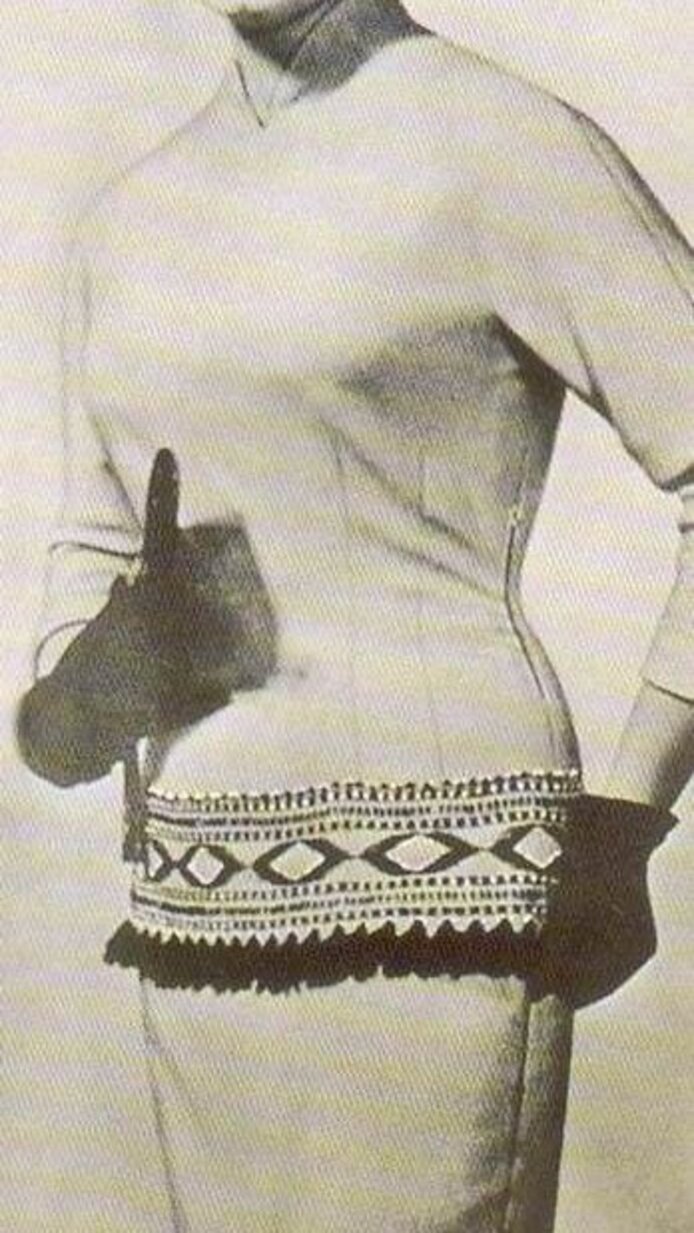

Even if silk, sequins and fur were reserved to Russian high society, regular Soviet women were not to be denied the opportunity of adopting the style of their favourite designers and adding their own modifications. In the 1960s, both West and East were caught up in the do-it-yourself trend. The most popular Soviet women’s magazines of the time, Rabotnica (Working Woman) and Sovetskaja ženščina (Soviet Woman) reveal the target group they addressed: the average woman who likes to produce her own clothes not only because of lack of money and of goods available in shops, but also as an expression of her own creativity. Female fashion designers such as Coco Chanel were her idols and the instructions for making a Chanel knit suit became common currency. Moreover, successful women such as Chanel contributed to feminising fashion and made it a medium of cultural transfer. Western fashion trends were not merely imitated, as Hausbacher emphasises. “Instead, a hybrid fashion developed incorporating Soviet notions of style and taste, which fostered a unique development of Soviet fashion and everyday culture.”

New role models and research contributions

The debates on style and taste of the time also involved issues of gender construction. The widespread “mannish” image of Soviet women – characterised in films by the female head of a factory, for instance – became increasingly feminine. For the decade between 1954 and 1964 the researchers found an increasing difference between female and male garments. “This correlates with the advent in Russia of the so-called Dior look”, notes Hausbacher. As of the mid-1960s until the 1970s, fashion language reveals an emancipation of women, originating especially among the younger generation. The Soviet woman now dressed unconventionally; she was fashion-savvy and not a slave of traditional role models. From the late 1970s onward, the boundaries between masculine and feminine looks began to blur. – Miniskirts were replaced by a more “butch” style with bellbottoms and shirts. The scientific investigation of fashion in clothing as a medium of cultural transfer reveals important elements of a new perspective on social developments and changes in the Soviet Union during the Cold War. It brings to light a more dynamic picture of Soviet society at that time than had been visible previously and thus makes an important contribution to further socio-political and cultural-history research. At the same time, the scholars were able to document the hitherto under-researched history of Eastern fashion in their basic research project and relate it to existing know-how on the far more popular fashion studies in the West.

Personal details Eva Hausbacher heads the Slavonic Studies Department at the University of Salzburg. She is a professor of literature and cultural studies and also conducts research on Russian literature from the 20th and 21st centuries, migration, gender studies and fashion. Hausbacher was the principal investigator of the five-year FWF project Needle and Thread. Transformation in Soviet Dress.

Publications