What court proceedings on papyri reveal about life in the Roman Empire

Ptolemy, son of Diodorus, knew how to deal with problems. In the 140s AD, he was a landowner in the village of Theadelphia in the Fayum, about 100 km south of Cairo, and he tolerated no grief from the authorities. At that time, Egypt was a province of the Roman Empire, and Ptolemy had leased alluvial land suitable for livestock farming, hunting and fishing from the procurator’s office that administered the imperial land. He found that the area’s sophisticated irrigation system did not supply him with enough water. Corruption may have been to blame – one document suggests that Ptolemy refused to pay protection money to the authorities. At any rate, Ptolemy seemed to have been knowledgeable about rhetoric and the law. He took the responsible officials to court and did so successfully.

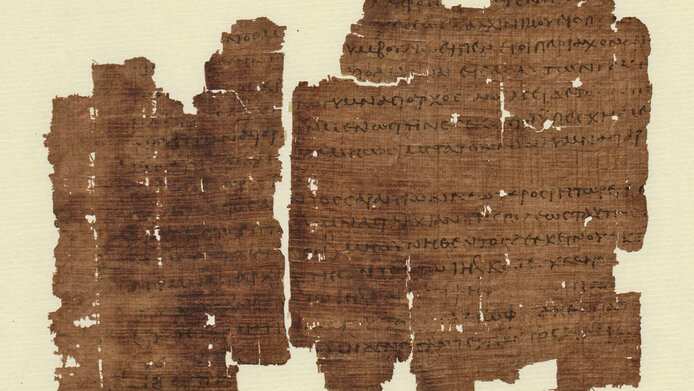

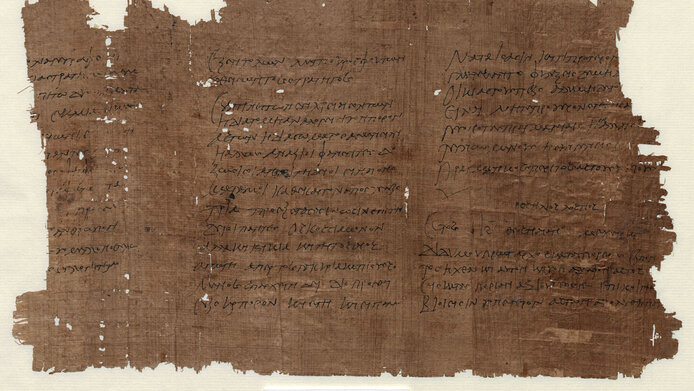

The story of Ptolemy's legal dispute was recorded on papyrus, a standard documentary medium on the ancient Mediterranean. Unlike other parts of the Roman Empire, in Egypt papyri have survived for millennia in dry desert conditions. A Vienna-based research team composed of Bernhard Palme, Professor at the Institute of Ancient History and Classics, Papyrology and Epigraphy at the University of Vienna, and Anna Dolganov of the Archaeological Institute of the Austrian Academy of Sciences (ÖAW), is investigating these valuable historical sources under a magnifying glass, quite literally. In the project “Roman Court Proceedings in Papyri: New Documents, New Perspectives,” which is being funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF, the researchers are not only deciphering previously unedited fragments, but are also focusing on existing editions of papyri, many published a long time ago which need to be revised, supplemented, and reconciled with the current state of research. In their work, the researchers draw on the rich holdings of the Papyrus Collection of the Austrian National Library (ÖNB), of which Palme is director.

Global significance for ancient Rome

The analysis of these legal documents adds to our knowledge of life in Egypt under Roman rule – but not only that. “Dating from the third century BC to the seventh century AD, the papyri are also of interest in a much broader sense,” Palme explains. “For example, they show how Roman law was applied in the provinces. In this context, Egypt becomes a model case, illustrating what administration and life were like in the Imperium Romanum. After all, public institutions were organized in the same way throughout the empire.” Palme and Dolganov thus refute a conservative doctrine that considers Egypt to be a “special case” without much relevance to our view of the entire Roman Empire. “Viewing the papyri as a source for the entire Roman judicial system is an innovative take. No one has yet granted this documentary evidence such global significance,” notes Dolganov. “We would like to propose that this view also be adopted in related fields, for instance to find out more about Roman archival institutions and the private economic life of the inhabitants of the empire.”

Almost 1900 years ago, Ptolemy was able to attract the attention of the Roman fiscal administration with his claim. Dolganov's review of the case shows that the landowner managed to get compensation for his loss that was the result of the water shortage. A high-ranking local administrator, who was responsible for irrigation, had to pay a sizeable sum out of his own pocket. “Ptolemy wrote all of his own petitions. This is very rare in known cases and suggests that he was a legal practioner himself,” the historian describes. “Moreover, his family owned several houses, including one in Alexandria. That meant he was able to spend a lot of time on the spot to conduct litigation without incurring high costs.”

Challenging deciphering of fragments

Many of the papyri describing cases like the one of Ptolemy do not come from well-preserved archives. Often they are just small snippets of informal private copies of court records that ended up in ancient landfills at some point. These fragments must be painstakingly restored, deciphered, supplemented, and contextualized by consulting other sources. “Each scribe had his own handwriting. But even at that time, handwriting changed over the decades. In paleography, which is the study of ancient writings, we are always dealing with new phenomena that have to be recognized and classified,” says Palme. “In addition, the transcripts are written in a distinct official style – not unlike the officialese one finds in documents today. It is only step by step that the juridical meaning of this language may be deduced,” adds Dolganov, who often spends many days deciphering individual fragments.

The papyri depict a world in which the legal conflicts of the population were mediated by an elite, well-connected group. As the representative of Rome, the governor was responsible for upholding the law and served as the supreme judge within a province. The lawyers were part of his entourage and usually knew each other well. They competed against each other in individual cases. “The governors' concern to uphold law and order often turned conflicts into show trials. They became propaganda performances designed to showcase how blessed the province was to be under Roman rule,” notes Palme. The cases that were tried here over generations reveal entire family histories. “We find endless disputes over inheritances or on the question of how to divide a property after a divorce. Another issue that arises often is tax evasion. Like today, the cases are very often about money,” says Dolganov.

Highly developed bureaucracy

The historical sources shed new light not only on everyday life in the Roman Empire, but also on a bureaucratic culture that was unique in antiquity. The numerous protocols, certifications and transcriptions that have been produced and systematically archived offer an extraordinary wealth of information on social and cultural history. “Our research is also partly about gaining a better understanding of the different types of texts – ranging from state court documents to private, abridged accounts of a legal case – in order to be able to distinguish them by means of their formal structure,” Dolganov explains.

The bureaucracy of Roman antiquity is also interesting from the point of view of policy-makers today, who are often confronted with calls for greater transparency. “It is amazing how well organized the state archives were. Everything was documented, and any free inhabitant of the empire could get copies of excerpts. This even included the official correspondence of public officials,” Palme notes. In view of today’s debates about official secrecy, politicians’ chats and the like, the pre-modern administration of the Roman Empire suddenly feels very modern.

Personal details

Bernhard Palme is Professor of Ancient History and Papyrology at the University of Vienna.In 2009 he was appointed director of the Papyrus Collection and the Papyrus Museum of the Austrian National Library (ÖNB). His research focuses on the history and culture of Greco-Roman Egypt and the historical analysis of papyri.

Anna Dolganov is a Roman historian and papyrologist at the Austrian Academy of Sciences (ÖAW), where she was awarded a Fellowship of Excellence in 2022. Having completed her studies at Harvard, Cambridge, and Princeton, Dolganov currently focuses on the legal and institutional history of the Roman Empire. The project “Roman Court Proceedings in Papyri: New Documents, New Perspectives” received EUR 285,000 in funding from the Austrian Science Fund FWF.

Publications

Dolganov, Anna: Rich vs. poor in Roman courts: a new text and interpretation of three judicial records from Roman Egypt, Tyche 37 2023 (in press)

Dolganov, Anna: Forgery and fiscal fraud in Iudaea and Arabia on the eve of the Bar Kokhba revolt: a memorandum for a trial before a Roman official (P. Cotton), Tyche 37 2023 (in press) (with Fritz Mitthoff, Hannah M. Cotton and Avner Ecker)

Dolganov, Anna: Law as competitive performance: performative aspects of the legal process in Roman courts, in: C. Bubb, und M. Peachin, M. (eds.), Medicine and the Law Under the Roman Empire, 66–123 Oxford 2023

Dolganov, Anna: The Administration of Justice in the Roman Empire: Sociology and Institutions. Cambridge University Press 2023 (in preparation)