Welfare state born out of crisis

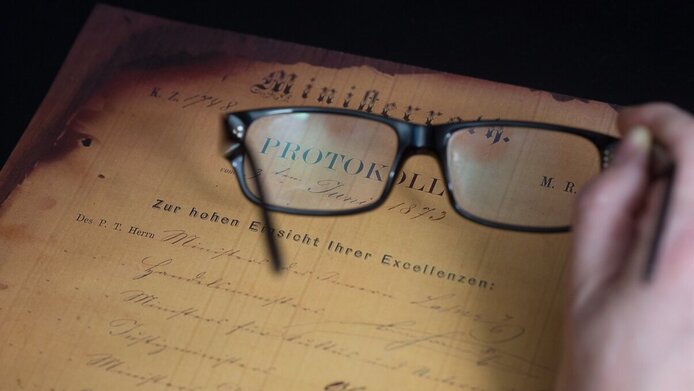

Between the years 1861 and 1918, the Presidium of the Habsburg Monarchy’s Council of Ministers archived more than 900 boxes and 100 bundles of files. These boxes also contained the minutes of the Austrian-Cisleithanian Council of Ministers from 1867 until the end of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. The Austrian-Cisleithanian Council of Ministers formed the government for those areas which belonged to the Austrian (Cisleithanian) half of the Empire. The final repository for these documents lay in the archives of the Justizpalast, the Palace of Justice in Vienna. When the building went up in flames on 15 July 1927, most of the documents were destroyed." About ten percent of the 900 boxes are left. As regards the minutes of the weekly meetings of the Council of Ministers, 750 items have survived entirely or in part”, says Stefan Malfèr, a historian at the Institute for Modern and Contemporary Historical Research of the Austrian Academy of Sciences (ÖAW). He has been involved from the outset in editing The Minutes of the Council of Ministers of Austria and of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. Research on these minutes has meanwhile become a fixed component of the ÖAW’s Cultural Heritage Research Unit. With the support of another team member, Malfèr was able to complete the elaborate processing of the Brandakten (“fire-damaged files”) for the years 1914 to 1918 as part of a research project funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF.

Salvage whatever can be salvaged

When in 1927 the archive shelves, several metres in height, collapsed in the fire, some of the boxes were buried by the debris, which shielded them from the flames. They were damaged, however, by the water used to fight the blaze. Partly risking their lives, the archivists salvaged the files, dried them out and tried to conserve as many as possible. Some minutes of Council of Ministers’ meetings were restored and preserved at a later date. “When we opened the boxes, there were only small fragments left of some of the documents. We took photographs on the spot, page by page, of any minutes that were well-preserved”, says principal investigator Stefan Malfèr. In order to reconstruct when each meeting took place and which ministers discussed what topic, the records of the Kabinettskanzlei (Cabinet Office) are just as important as the copies preserved in Czech archives. “Minutes that are completely preserved are few and far between. For the years 1915 to 1917 we unfortunately have only a small number,” adds project-team member Wladimir Fischer-Nebmaier, a historian and Slavicist.

The food problem was underestimated

One of the reasons why the minutes of the Council of Ministers hold so much interest is the fact that the discussions at the meetings were not a matter of public record but confidential. The minutes of what was said, partly in great detail, provide present-day scholars with almost first-hand information about government policies of the time: Which topics were particularly sensitive? Which ministers adopted what positions? Which lines of conflict existed and what changes can be observed in the debates? According to Fischer-Nebmaier, two topics – food and authoritarianism – were relevant throughout. In October 1914, for example, there was a first food crisis, which was closely linked to the railway situation. “For weeks, military goods always had priority under the wartime transport regulations. The civilian population was not allowed to use the railway, and there were hardly any trains that brought food for civilians,” explains the historian in the interview with scilog.

This quickly led to supply bottlenecks in many cities. The Council of Ministers discussed these issues, and the minutes provide insights into how the situation developed. According to the historians, the Prime Minister at the time, Count Karl von Stürgkh, realised that the food issue could be decisive for the war outcome and tried to explain it to the army leadership – albeit without success. Various solutions were discussed and implemented, but the problem became worse and food remained on the agenda until the end of the war.

The rocky road to the welfare state

“The minutes enable us to ‘listen in’ to what the ministers actually said at the time,” Fischer-Nebmaier points out. He was impressed by the radical switch from an extremely authoritarian policy to the “discovery,” at a relatively late point in time, of social issues in 1917. At the beginning of the war, the Minister of Trade still opined that hunger was a good thing, since it meant that the need for food would drop. “After 1917, such cynical remarks were no longer made in the Council of Ministers. Instead, the ministers now talked about how the civilian population was faring and what they required,” notes the historian. The tenacious resistance on the part of some ministers stemmed from the fact that they equated a social agenda with the workers’ movement, which they felt should be accorded as little political weight as possible.

At any rate, Social-Democrats were invited to take part in government already before the end of the Monarchy on 11 November 1918. Stefan Malfèr considers structural weakness to be the main reason for the retarded evolution: “The wrong people, viz. the military, held too much power for too long. When the empire was defeated in the First World War, their influence vanished.” The minutes of the Council of Ministers are now available as a historical source either for the first time or in a better form than before, and they have been contextualised. There will be a full digital edition of this volume that will be accessible on the ÖAW website. These efforts save the remains of the original 900 boxes from oblivion. Who knows what other insights are still hidden in them?

Personal details

Stefan Malfèr is a historian specialising in the administrative and legal history of the Habsburg Monarchy in the 19th and 20th centuries. He has been involved in the editing of The Minutes of the Council of Ministers of Austria and of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy since 1976. Most recently, Malfèr headed an FWF project relating to the minutes of the Cisleithanian Council of Ministers between 1914 and 1918. Wladimir Fischer-Nebmaier is a historian and Slavicist at the Institute for Modern and Contemporary History Research of the Austrian Academy of Sciences and is the main project officer in the FWF project. He is also responsible for the digital edition of the World War Volume.

Publications (in German)

Stefan Malfèr (Hg.): Die Protokolle des cisleithanischen Ministerrates 1867-1918, Band I: 1867, Wien 2018

Online Edition: „Die Ministerratsprotokolle Österreichs und der österreichisch-ungarischen Monarchie 1848-1918“, Institut für Neuzeit- und Zeitgeschichteforschung, ÖAW