“We should be vigilant”

At the beginning of 2017, an art project by the German-Israeli satirist Shahak Shapira unleashed fierce controversies in the social media: the artist combined the selfies of people who had used the Holocaust Memorial in Berlin as a backdrop for their social-media profile photos with historical footage of extermination camps. The photo collages on “Yolocaust” portrayed tourists juggling in front of skeletons or jumping up and down on piles of corpses. With his project, Shapira wanted to “encourage people to reflect on what the Memorial is all about”. Despite the fact that Peter Eisenman, the architect of the Memorial, described his work as an unhallowed place where “people will picnic on the grass and children will play tag”, the way tourists behave beside the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe is still inappropriate. “I actually liked the project”, says the contemporary historian Dirk Rupnow, “since people often no longer associate any message with memorials. For students in proseminars today, the Holocaust is as distant as the Middle Ages. They have little concrete knowledge, but at the same time they are supersaturated and feel that they already know everything. That is a problem”, concludes Rupnow, who is the Dean of the University of Innsbruck’s Faculty of Philosophy and History.

Political irritations

The historian was a visiting professor at Stanford University in 2017, when President Donald Trump was inaugurated and shortly afterwards raised political hackles with numerous statements – including about commemorating the victims of the Holocaust. On 27 January, the very day on which the victims of the Holocaust are commemorated worldwide, Trump announced his restrictive immigration and refugee policy. On the same day, the White House made no mention of the six million Jews murdered in its Holocaust Remembrance Day statement. A few months later, Trump caused uproar with a very short visit to the important Israeli memorial Yad Vashem and an incongruous entry in the memorial book there. He wrote: It is a great honour to be here with all of my friends - so amazing + will never forget. “That is the kind of thing you write when you are up on the top of the Zugspitze and admire the view”, was the comment on this entry by Moshe Zimmermann, professor emeritus at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

Commemorative culture between forgetting ...

For Dirk Rupnow, these examples are an opportunity to examine current developments in the culture of memory. “The Holocaust is the only historical event whose memory is institutionally secured not only in individual countries, but on the European and global level”, he notes. Over the past twenty years, standards have been defined as to what this commemoration should entail and how it should be communicated to younger generations. This is also linked to the attempt to ensure harmonisation of the substance of this memory. Rupnow perceives a difficulty for memory culture in the fact that the Holocaust is sliding into the past, becoming more and more isolated from the present, while being simultaneously exploited at the political level.

... and political instrumentalisation

“Some use memories of the Holocaust to demand a more humane approach to refugees by comparing refugee camps with concentration camps. Others, however, advance the dire argument that the majority of the refugees are anti-Semites, and lessons learned from the Holocaust should forbid their entry into Europe – which is tantamount to pretending that anti-Semitism no longer exists among the indigenous population of Europe. In this way, the Holocaust memory serves to exclude groups from society once again. That’s worrying”, says the historian.

Remembering helps to recognise developments in time

According to Rupnow, remembrance has the important task of recognising in good time the emergence of certain structures that already existed in history - this requires making a connection to what is happening today, but without direct comparisons. “Historians never make comparisons in the sense of saying that events are identical, instead they try to gain an understanding of certain situations, for instance situations as we see them today, where moods suddenly turn and justifications are found for excluding groups from society”, explains the scholar, citing the rise of right-wing populism both in Europe and worldwide as a current example.

From Berlin ...

Raised in (West) Berlin, Rupnow first studied history, German language and literature, philosophy and art history in his hometown. There is a historically significant reason for the fact that he began his studies a year later than originally planned: in 1989, the Berlin Wall came down. “Life with the Wall was normal for my generation; we knew that we couldn't just simply leave the city for a quick drive around”, recalls the 46 year-old scholar. West Berliners did not have to do military service either. The collapse of the Wall changed that. So Rupnow suddenly and unexpectedly did community service in a Berlin hospital. “I was the first one there. They didn't even know what to do with me”, he recounts. The fact that the vibrant theatre and music scene of East Berlin also became accessible to him at that time was something he greatly appreciated.

... to Vienna

His enthusiasm for theatre and opera was an important reason why the young student chose Vienna for his Erasmus year in 1996. "In the evening I was to be found either at the Burgtheater, at the Musikverein or at the State Opera”, he smiles. The plan was to stay for one year, but he stayed on for many more. After graduating in Vienna, Dirk Rupnow was a research assistant at the Historical Commission of the Republic of Austria in 1999. Following his doctorate in 2002 at the University of Klagenfurt, he was a visiting scholar at several institutions, including Duke University in North Carolina, the Simon Dubnow Institute for Jewish History and Culture at the University of Leipzig, and the Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC. In 2009 Rupnow acquired his professorial qualification in Vienna and joined the Institute of Contemporary History at the University of Innsbruck. “Ultimately, my career was the result of many coincidences”, he summarises.

New focus on migration research

In Innsbruck, the historian's research interests shifted more towards diversity and migration. He established migration history as a new research focus at the Institute of Contemporary History and, in 2015, founded the "Research Centre Migration & Globalisation", which brings together a working group of colleagues spanning several disciplines and faculties who deal with the topic of migration from various perspectives such as European ethnology, political science, architecture, philosophy and education science.

Migration Society Austria

A year ago, Dirk Rupnow completed the FWF-funded project Deprovincializing Contemporary Austrian History. Migration and the transnational challenges to national historiographies. “Migration was virtually absent from the history of Austria as a republic”, the historian relates in describing the starting point of this project, but “visibility in history is an important basis for social acceptance”. This project focused on the migration of migrant workers, then called ‘guest-workers’, during the 1960s and 1970s, a time that Rupnow describes as a “turning point” in Austrian history – since it made Austria an immigration country at least in statistical terms.

Laborious search for sources

Dirk Rupnow was particularly interested in a transnational perspective beyond the scope of just Austria. With his team of six he embarked on a painstakingly detailed search for sources. A search that also turned out to be very difficult in Austria, as so little material had been preserved: “It was assumed that the ‘guest workers’ would leave the country again and people often saw no need to archive their files”, Rupnow explains as to this finding. In the countries of origin - mainly ex-Yugoslavia and Turkey – the researchers have tried to find files that illustrate the interests and perspectives of the countries of origin through recruitment contracts and the concomitant processes. There, too, a great deal of information had disappeared or been destroyed. “The search for sources is highly complicated. Sometimes you're lucky, sometimes you’re not”, Rupnow concedes.

Archive of migration as collective memory

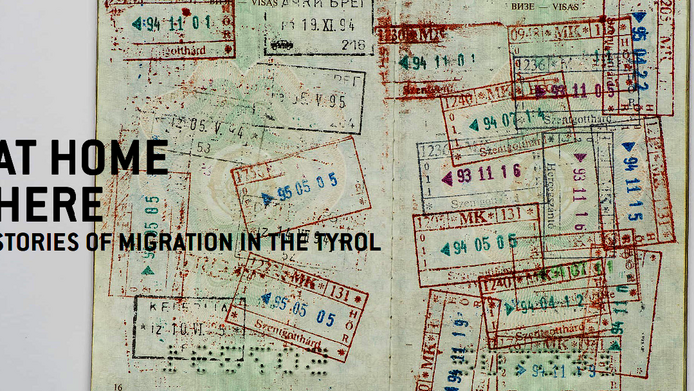

As a result of this FWF-supported project, the researchers perceived the need for an “archive of migration” as a basis for a new collective memory. In the meantime, several Austrian provinces have set up institutions that archive materials and documents on the history of migration. Tyrol is a case in point: the University of Innsbruck there, together with regional partners such as the "Centre for Migrants in Tyrol" and the Landesmuseum, is setting up a documentation archive whose collections are open to the public. “The FWF project has provided a good platform for sensitising people to the need for such an archive”, Rupnow summarises. The results also flowed into a wide variety of educational projects, such as an exhibition at the Volkskunstmuseum Tirol (“At home here”, 2017) or the exhibition Geteilte Geschichte. Viyana - Beč – Vienna, which ran until February 2018 at the Wien Museum.

Migration and diversity remain big issues

Rupnow considers the completed basic-research project on guest-worker migration as only the beginning: “Just how Austrian society changes as a result of migration will remain a huge topic for contemporary history in the coming years: How does migration shape and transform society? How does diversity in society change the way we look back at periods farther in the past, such as the Nazi era and the Holocaust? And how do we interpret these stories against the background of our current experience? These are the big issues for the next few years."

Position counter to the mainstream

Does he see himself in an advisory capacity vis-à-vis policy-makers? “We are happy when our expertise is sought. But for us it is always very important not to let ourselves be used for specific purposes. In the spirit of critical migration research, we see it as our task to create a public sphere even for uncomfortable opinions and to take a position that runs counter to the mainstream”, Rupnow explains. At the same time, he is also confronted with expectations that he will solve social problems in his capacity as an academic. The researcher has always been intrigued by this complex and difficult field, given that he works on topics of pronounced public relevance. “At the Institute in Innsbruck, we also conduct many regional projects relating to the Nazi past, for example on forced sterilisation during the Nazi era, or on critical aspects of post-war history, such as institutional education in children’s homes, which are sometimes initiated on the political level and conducted by committees.” The issue of how to navigate these diverse contexts - also in connection with funding - is something the researcher always has to keep in mind.

Devaluation of research

As far as the role of research is concerned, Rupnow is very concerned about current developments. “The devaluation of science and the validation of rumours as ‘sound evidence’, the simultaneous establishment of ‘alternative facts’ and Trump’s elite and science bashing – these are phenomena we also see in Europe. There is a lot going on at the moment, and all of us in the scientific community should be vigilant”, says the researcher sounding a note of warning.

Personal details

The historian Dirk Rupnow has been Dean of the Faculty of Philosophy and History at the University of Innsbruck since March 2018. Prior to that he was head of the Institute for Contemporary History at the University of Innsbruck as from 2010 and founder and head of the research centre "Migration & Globalisation" as well as of the doctoral college "Dynamics of Inequality and Difference in the Age of Globalisation". His research focuses on European history of the 20th and 21st centuries, Holocaust and Jewish studies, the history of science and migration, memory cultures, museology and historical politics. Born in Berlin, he studied history, German language and literature, art history and philosophy in Berlin and Vienna. He worked for the Historical Commission of the Republic of Austria and completed numerous research stays, including at Duke University in North Carolina, the Simon Dubnow Institute for Jewish History and Culture at the University of Leipzig and the Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies in Washington. In 2017 he was Distinguished Visiting Austrian Chair Professor at Stanford University.