The native tongue of the future is called translation

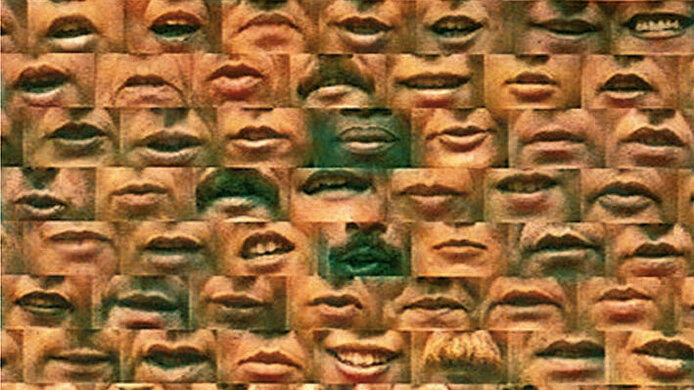

Griaß di, bonjour, iyi günler! Europe is marked, apart from its other characteristics, by language diversity. This has always been part of the continent's identity and that of its population groups. At present, however, a good deal of what has developed historically undergoes serious renewal. Due to migration and mobility, Europe is going through a process of transformation which raises many questions about European society in the future. With the support of the FWF, the interdisciplinary research project “Europe as a Translational Space” explored language and translation processes against the backdrop of societal change. In the project, the researchers primarily define translation as a social phenomenon. “Apart from standardised national languages, there is a great variety of different linguistic realities. This may include family languages, trade languages or, an aspect of growing importance, languages of migration”, explains Stefan Nowotny, a philosopher and member of the research team. “A differentiation into family languages and trade languages is known, for instance, in parts of Africa. As a result of migration they are now also spoken in French suburbs.” The researchers are convinced that these aspects need to be taken into account.

The administration of multilingualism in the EU

The European Union currently recognises 24 languages as official and working languages. The way in which this multilingualism is addressed is always informed by policy decisions and also by legal aspects, notes Nowotny. While every document that is part of the EU treaties must be translated into all official EU languages, each version is considered as an original to make it legally binding. “This is also an example of how the significance of translation often remains completely unacknowledged.” Nowotny, who has also lived in Brussels, uses the example of Belgium and Luxembourg to describe the impact different language policies may have on multilingual societies. According to the expert, Belgium pursues a multilingual model which ensures monolingualism to all language groups, particularly outside of Brussels. Luxembourg, on the other hand, is characterised by linguistic flexibility. There, most of the print media are in German, laws are published in French, whilst Luxembourgish, which is not an official language of the EU, dominates everyday life and radio and television; add to that English, which is taught in schools. – Diversity is and will remain a prominent feature of Europe. The question the scientists are now exploring is what benefits society derives from such diversity.

Language as a product of many influences

The FWF research project, which was conducted at the European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies (eipcp), included a series of workshops in the Parisian suburb of Aubervilliers, in Salzburg and in Maribor in collaboration with the local partners: Les Laboratoires d'Aubervilliers, Stefan Zweig Centre Salzburg and Goethe Institut Ljubljana. There the following questions were discussed with international scientists: how are social conditions articulated in situations of linguistic difference? Who is “addressed” in what way? And what are the political, social and economic factors that inform these practices or are challenged by improvised or informal translation communities? Heterolinguality, a term introduced by the Japanese translation theorist Naoki Sakai, constituted a central theoretical starting point for the project. “We believe that this concept offers a convincing instrument for the re-evaluation and recreation not only of linguistic practices, but also of cultural, educational and political practices”, says Nowotny. As one of the outcomes of this project, elements of a map of Europe as a translational space were developed in a number of print and online publications, at an international conference and in workshops.

Translation as an opportunity for Europe

Apart from theoretical approaches, the researchers also sought the co-operation of expert practitioners in the workshops from fields such as foreign-language teaching, interpreting in proceedings for asylum-applicants or work with young people. The process included creative work, such as film and music projects from and with young people where the creative use of language was the focus. “We have developed approaches that understand the necessities of translation not in terms of bridging a communication gap, a one-sided approach often heard in migration debates, but rather we saw translation as an opportunity to meet the challenges of the transformation processes in modern-day societies”, explains Stefan Nowotny. The scientists are convinced that the project of European integration has reached a critical point. What language is the European public expected to speak in the future? “The answer can be neither one given national language, nor a purely mechanical aggregation, i.e. multilingualism”, notes Nowotny. The functioning of a shared democracy requires an appropriate public sphere. “In order to fulfil its democratic functions this public sphere also needs to have a common language. Today, this common language can only be the language of translation.”

Personal details Stefan Nowotny holds a PhD in philosophy. He teaches at Goldsmiths College, University of London, and is a member of the Vienna-based eipcp - European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies. His research and teaching centre mainly on political theory, linguistic and social aspects of translation and the entanglements of historical and contemporary epistemologies and imaginaries. He is the author and co-editor of numerous publications.

Publications

"The Languages of the Banlieues": http://eipcp.net/transversal/0513

"A communality that cannot speak: Europe in translation": http://eipcp.net/transversal/0613