The emperor sends out soldiers

In the 18th century, the Habsburgs waged three wars against the Ottomans in their provinces in southeastern Europe. Sabine Jesner is less interested in identifying which generals fought for what territory and how the battle ended than in the toll these conflicts exacted in terms of money and bloodshed. This military historian from the University of Graz has coaxed out a great deal more information than just a victory here or a defeat there based on the archival material on Habsburg field hospitals, which she has vetted for the first time for her Firnberg project: “The military was ubiquitous and affected all levels of society. New military history involves bottom-up historical research, which tells us a lot about the civilian population.” Even though in Jesner’s eyes the evolution in the 18th century is “not exactly a success story, the material reveals precursors to what we know today as public health ideas, which means state care and responsibility for the health and wellbeing of the population.”

Tracking health policy

While researching for her dissertation on the military frontier population in Transylvania, Jesner came across the “Cordon Sanitaire”. In the context of a peace treaty concluded in 1718, after the “First Austro-Turkish War”, the Habsburg Empire’s external border from the Adriatic to the Carpathians was gradually equipped with strict controls and quarantine facilities, because the plague was raging in these regions. That was a rather unique measure on European territory, combining both military and health objectives. This is the state of affairs that Jesner, a specialist for the region of Southeastern Europe, is concentrating on in her project, which is supported by the Austrian Science Fund FWF.

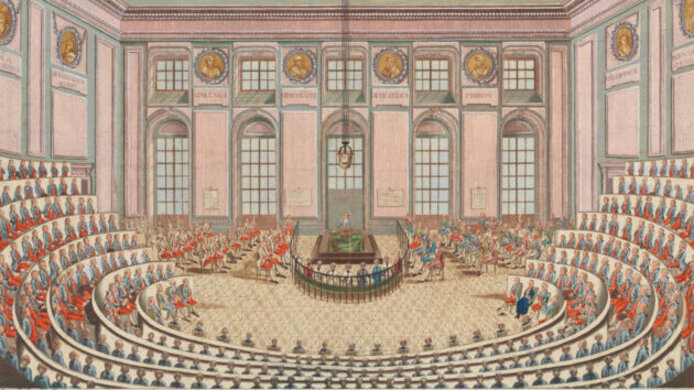

From the capital city Vienna, the “management” in place at the time, consisting of the General War Commissariat, the Aulic War Council and the Hofkammer, the central financial authority, sent tables, orders and instructions to the provinces. This administrative correspondence provides glimpses of the socio-historical perspective in which Jesner is interested, starting under Charles V, his daughter Maria Theresa and her son Joseph II. The “Second Austro-Turkish War” lasted from 1736 to 1739, the third from 1787 to 1792.

The general framework

“What was often worse than the enemy were the lack of supplies, the long marches with inadequate footwear and, depending on the region to which the troops were sent, also malnutrition and little drinking water,” notes Jesner. The brutal situation on the 18th century battlefields in what is now Hungary, Romania, Croatia, Serbia and Bosnia was the result of a combination of noise, soot, bad weather, weapons that didn’t shoot straight and the fact that the wounded were not recovered until after the fighting had ended. The ancient theory of the four humors was the medical doctrine prevailing at the time. A mercenary army was transformed into a standing army, which was recruited and supplied with provisions in barracks during lulls between specific campaigns. In barracks construction and field medicine, the idea of prevention slowly began to take hold. And there was continuing care for invalids no longer fit for military service.

In order to ensure the constant supply of troops, the administration had to cooperate with the civilian population – both men and women – for obtaining necessary supplies, and they had to plan ahead (beds, linen, food, clothing, transportation and more). Soon, precise rules evolved for how many physicians and surgeons would be employed, and what rations would be issued. “As always, as soon as money is involved, everything is well documented. And those who fight get less than those who direct the fighters.”

Informative statistics and a chief logistician

Sabine Jesner has learned to read between the lines of statistical tables and letters: “I also wanted to shed light on the emotions surrounding the events of the war, but most 18th-century soldiers were unable to read and write. Sometimes one comes across a short statement about this from the upper echelons. The figures on deserters and self-mutilations in the statistics speak to me of the fear and panic.” Management did actually respond to the field reports. In order to prevent scurvy, the troops were sent vitamin C in the form of horseradish roots. Given that there was hardly any wood available in Croatia, instructions for building field hospitals were put together in Vienna and sent down the Danube together with the building material for wooden huts, not unlike an IKEA package.

Alessandro Brambilla, the personal physician to Joseph II, acted as a kind of chief logistician in the second half of the 18th century. He later established the Josephinum as a medical-surgical academy and liked to send topical scientific literature to the staff surgeons. It was as a function of rational thinking that the regime took care of the population, ensuring services such as sanitation, hygiene and nutrition, and sought constant improvements to minimize suffering. Although success was often modest, there were attempts on the part of headquarters to address conditions on the ground.

Prevention, care & aftercare

Jesner perceives precursors of the public health principle in the mercantilist approach, which always follows rational arguments but, as a result, acts humanely. “There was medicalization ‘from the top’, because the rulers wanted a healthy population fit to do proficient work. For me, this is the most important finding: the preventive and anticipatory approach of the state, which assumes responsibility and defrays costs, and reflects on what will be needed to achieve goals,” Jesner says. Key indicators were created over time, in a quite pragmatic way, with the aim of improving and optimizing military operations.

The state created new “medical spaces”, such as homes for wounded soldiers after the first Turkish War or military hospitals with fixed equipment. Those men who were no longer fit for field service after the missions – for psychological or physical reasons – were taken care of by the state. Invalids were settled in border military zones, for example in the Banat (on the southeastern edge of the Hungarian Plain), provided with land and, depending on their degree of fitness for work, deployed as free peasants for guard duty.

Personal details

Sabine Jesner, a historian of the early modern period, acquired her PhD from the University of Graz with a thesis in the sphere of Southeast European history on Habsburg security and prevention strategies at the Transylvanian military border. As of 2015, she investigated Habsburg administrative techniques in the Banat as member of an FWF project team. In 2020, she was awarded the Johann Wilhelm Ritter von Mannagetta Award for the History of Medicine (ÖAW) for her studies on the Habsburg Cordon Sanitaire. The project “Habsburg field sanitation and the Austro-Turkish wars of the 18th century” (2019-2023) received EUR 239,000 in funding from the Austrian Science Fund FWF.

Publications

Beyond the Battlefield: Reconsidering Warfare in Early Modern Europe, London 2024 (in Druck)

Borders and Mobility Control in and between Empires and Nation-States, Brill 2022

Medicalising borders: Selection, containment and quarantine since 1800, Manchester University Press 2021