The cultural capital of refugees

“There is no architecture worthy of the name, no professional theatres, the art galleries are terrible,” reads a disillusioned comment in Gertrude Langer’s diary. In 1938, the art historian fled to Australia via Athens together with her husband, the architect Karl Langer. The couple settled down in rural and provincial Brisbane. Langer's diary entries tell the story of a long, challenging journey in her new homeland, where she found a cultural vacuum. In small steps and over many years she was able to make a reputation for herself as an art expert, revolutionizing the art sector in Queensland and finally becoming one of the trailblazers of modern art in Australia. Gertrud Langer's fate was shared by many, including Gertrud Bodenwieser. Bodenwieser was a pioneer of modern expressive dance in Vienna and fled to Australia before the outbreak of the Second World War. In a small studio in Sydney, the successful choreographer and dancer developed the Australian variety of modern dance.

Migration history using Australia as an example

When the Anschluss and the imminent outbreak of the Second World War cast their shadow in Austria, the Jewish population scattered all over the world. Only a few of them, however, set out for faraway Australia, which pursued a restrictive immigration policy in the 1930s. It was not until early 1939 that the country relaxed its restrictions and allowed 15,000 refugees to enter the country over a period of three years. Between 1938 and 1945, a total of around 9,000 people from German-speaking countries ended up in exile in Australia. They settled mainly on the south-east coast of the country, in the cities of Melbourne, Sydney or Brisbane. Among them were at least 2,600 Austrians, most of them from Vienna. The contemporary historian Philipp Strobl has now followed the tracks of these refugees and outlined the migration history of the Second World War and its consequences using Australia as an example.

About the project

Austria's Forced World War II Migration to Australia analysed the consequences of the migration of a cohort of Austrian World War II refugees in Australia. It researched and wrote a collective biography of 26 refugees who came to Australia before and during the war focusing on their memories and depictions of their contribution to the social, economic, and cultural transformation in wartime and post-war Australia.

The impact of knowledge transfer

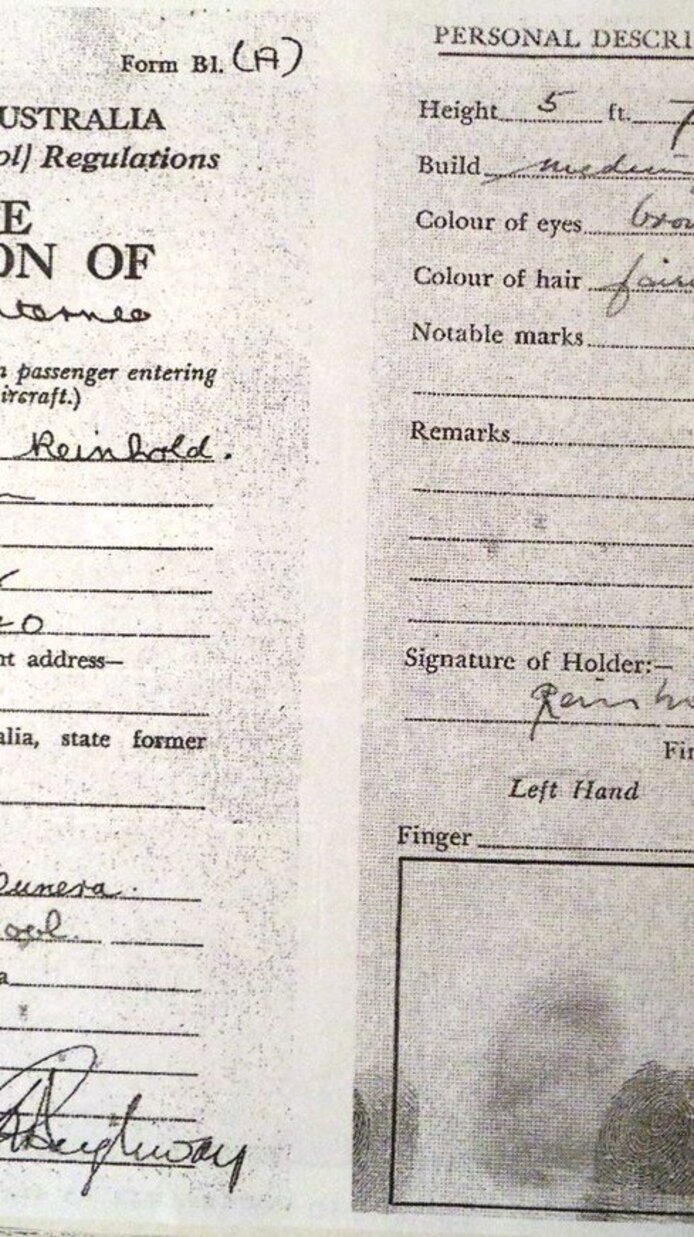

“Compared to the USA or the UK, Australia has an excellent archival culture,” reports Philipp Strobl. This enabled the researcher to access the completely preserved naturalization files and many other sources he used as the basis for compiling an accurate profile of the Austrian refugees in Australia. Using these statistical analyses, Strobl, whose research project was funded by a Schrödinger grant from the Austrian Science Fund FWF, selected and interviewed a representative group of 26 people (one percent of the total refugee cohort). He is currently working on the complete edition of this “collective biography”, as he calls it, which will be published in 2020. Strobl has already published a number of articles on individual case studies. The individual fates show what contribution Austrian exiles made to the economic and cultural development of Australian post-war society. The memories of the refugees are above all evidence of an enormous transfer of knowledge from the cultural centres of Europe to the sparsely populated fifth continent.

Progressive thought and action

“The emigrants built on their cultural capital, because they were financially in dire straits due to the Reich Flight Tax and the high costs of the crossing to Australia, and these displaced individuals also had to support themselves,” explains Philipp Strobl. Coming mainly from a middle-class background, many of them were highly qualified university graduates. Among them were doctors, lawyers, architects, engineers, but also numerous entrepreneurs. The immigrants took advantage of this educational capital and started anew under the most challenging conditions. When Karl Anton Schwarz (Charles William Anton), an insurance employee by profession and passionate ski touring enthusiast in his leisure time, came to Australia, he didn't know that he, too, would become a pioneer. Enthusiastic about the possibilities of skiing, which at that time was only practised by a select few in Australia, Schwarz imported the concept of the Austrian Alpine Association, and through a membership system and mountain shelters he built up an infrastructure which prepared the ground for the development of skiing as a sport and a tourism industry in Australia. The biographies of the refugees illustrate the different contributions they made to Australia's economic and social development. “Much of what is now regarded as 'Australian' has an international origin,” Strobl emphasizes. The prejudice that refugees are still confronted with today shows the significance of this research on the history of migration, says the historian. Strobl therefore considers it important to show what impact refugee flows have had in the past in order to promote understanding of these processes and contribute to eliminating the anti-migrant bias.

Personal details

Philipp Strobl studied economic and social history in Innsbruck and from 2016 to 2019 conducted research under a Schrödinger grant from the FWF inter alia at the Swinburne University of Technology in Melbourne, Australia and the Institute of Contemporary History at the University of Innsbruck. Since 2019 he has been teaching and researching at the Department of History at the University of Hildesheim. Strobl's research interests include the history of migration, the history of networking, and transnational and global history.

Publications

Philipp Strobl: Migrant Biographies as a Prism for Explaining Transnational Knowledge Transfers, in: Migrant Knowledge 2019

Philipp Strobl: But the Main Thing is I had the Knowledge: Gertrude Langer, Cultural Translation and the Emerging Art Sector in Post-War Queensland (Australia)†, in: Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art 18/1, 2018

Philipp Strobl: Migration, Knowledge Transfer, and the Emergence of Australian Post-War Skiing: The Story of Charles William Anton, in: The International Journal of the History of Sport 33, 2016