The colonial echo of the First World War

A collection of audio recordings made by a group of mostly German researchers during the First World War with African prisoners of war provides the basis for Anette Hoffmann's project Listening to the Colonial Archive. From a collection of material in the Berlin Lautarchiv, the cultural scientist has set about translating and analysing these more or less dormant sources and placing them in their historical context.

Anthropological tourism

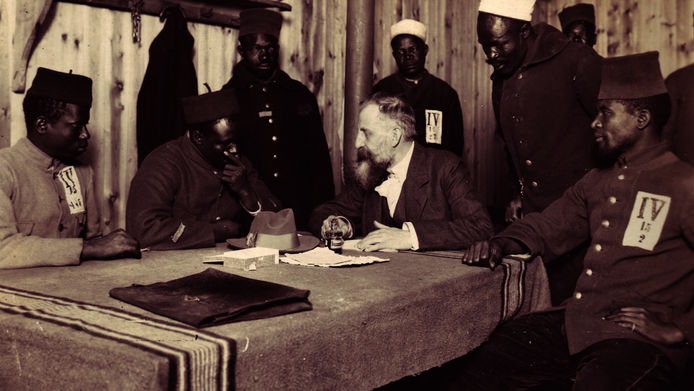

Colonial relations allowed European researchers to conduct racist research in Europe and in colonised countries. This was a time when the public would flock to Völkerschauen (‘human zoos’) where people from distant lands were put on display. The researchers most interested in such “exotic foreigners” were anthropologists and linguists, and sometimes also musicologists. During the First World War, around 650,000 soldiers were recruited from African colonies and brought to Europe. As the researchers regarded the presence of the prisoners as an opportunity, prison camps became destinations of “anthropological and linguistic tourism”, Anette Hoffmann notes in the interview with scilog. The researchers were not interested in the experiences of African soldiers, however, but rather in establishing a systematic documentation of all languages spoken in German prisoner-of-war camps, many of which were not understood at all.

Neglected archives

What has remained of their efforts is an “archive of distorted fragments which provides no information about the individuals, but merely broke them down into a kind of index”, as Hoffmann describes it. For today’s purposes, she relates, this archive turns out to be a remarkable documentation of the presence of African soldiers and lone immigrants in Europe, who used the standardised recording procedure for making interventions, requests, and even indulging in parodies. The recordings themselves also reveal connections to other archives. The trail of the Senegalese prisoner Abdulaye Niang, who asks not to be deported to Romania, leads to anthropological research undertaken on prisoners of war in Romania and ultimately to the records of the Austrian anthropologist Rudolf Pöch in Vienna. “There are countless sound recordings”, notes Anette Hoffmann, “which have left behind more traces than we thought, in addition to military registers, photographs and records of anthropological investigations. Until a few years ago, colonial historiography had not taken any notice of them.”

Listening between the lines

The challenging task in Anette Hoffmann’s research project, which is funded through a Lise-Meitner grant from the Austrian Science Fund FWF, is to listen to the language recordings with a view to filtering out the mood in the prison camps, the interview settings and any messages that might be hidden between the lines. In this context Hoffmann also uses the notion of echo, “which is always nearly, but not quite, the same as the original and thus enables us to identify a gap”. This concerns issues of extraction, limitation, distance or distortion arising from the speech files. Colleagues in Africa help her with the concrete translations of the various African languages. - Hoffmann has spent several years working at universities in South Africa and continues to do research there on a regular basis. Publishing her results – one volume based on the project is currently being produced – is not the researcher’s only objective. She also wants to offer them to a museum, a place where absolute silence still reigns, as Hoffmann notes wistfully. After sound installations in Stuttgart and Hamburg, further exhibition projects will follow, and the previously untapped audio sources will provide a colonial echo of the First World War and new perspectives for historiography. In the future, the researcher would like to focus more on the use of historical sound recordings in ethnographic museums.

Personal details Anette Hoffmann is a cultural scientist and Africa specialist. Under an FWF Lise-Meitner grant she is working on the project Listening to the Colonial Archive at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts until 2020. Hoffmann has been processing collections of historical sound recordings from colonial times for several years.

Publications