St. Stephen’s Cathedral: new facets of its architectural history

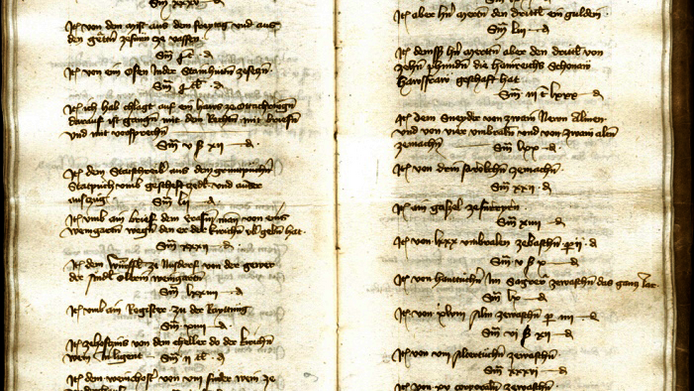

The fire at Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris in April 2019 alarmed and shocked people all over the world. These feelings resonated with many Austrians - after all, a major fire had threatened an Austrian landmark, St. Stephen's Cathedral, in 1945. A glance at the three-hundred-year construction history of St. Stephen’s in Vienna reveals that fire protection measures were already implemented in the Middle Ages after a fire in the wooden roof truss. The measures involved can now be understood in concrete terms for the first time on the basis of the church’s income and expenditure accounts, which were maintained by the Kirchmeister or church treasurer. That these annual accounts constitute an important historical source is well known to the art historian Barbara Schedl from the Department of Art History at the University of Vienna: “We found many entries in the treasurer’s ledgers relating to the emptying, filling and mending of water vats, for instance. These vats were put up in the roof in the Middle Ages, so that extinguishing water would be on hand quickly in the event of a fire. They were emptied and mended before winter.” Schedl is the first scientist in St. Stephen’s two-hundred-years research history to take the treasurer’s accounts seriously as a source, reading and analysing them in conjunction with other documents. It is only through accumulating a wide variety of sources that well-founded answers can be provided to questions about the cathedral’s construction history. Lost religious objects can be reconstructed Not only the South Tower, considered the highest church spire in Europe in 1433, but the building in its entirety was a remarkable feat at the time of its construction. Between 2012 and 2018, Schedl collaborated with institutions such as the Dombauhütte (the cathedral’s construction department) and meticulously examined all existing written sources on St. Stephen's Cathedral in the context of two research projects which were funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF. These sources include everything from builders’ invoices and letters of indulgence to last wills, deeds and the treasurers’ annual accounts. Of these annual accounts, 17 transcribed volumes from the Middle Ages, each around 28 pages long, have been preserved. A comparison shows how substantially the material base has been expanded: whereas only some 200 sources had been used previously, this number has now been increased to about 3,000 - more than ten times as much.

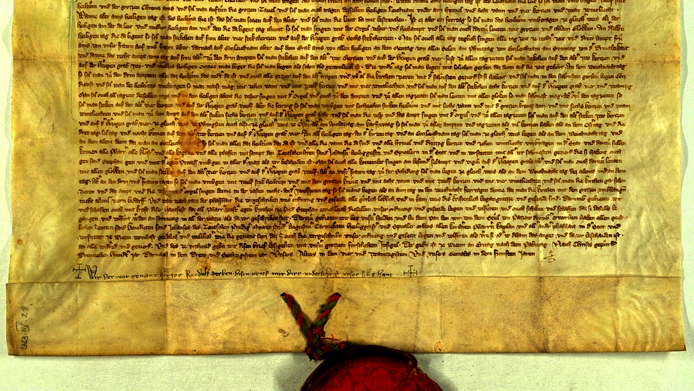

The initial research project was devoted to recording all available sources systematically for the first time. The follow-up project focused on religious objects referred to in written sources, including altars and pulpits, chests and chandeliers. Since all of these objects are no longer to be found, any written record of them constitutes an important source for historians. On the basis of these records, Schedl can identify the place that many of these items occupied in the cathedral and reconstruct what were their – in some cases varied – uses and purposes. Barbara Schedl’s interdisciplinary approach and working method have turned out to be very helpful. She was able, for example, to identify a textile item as being a protective cover for an expensive, elaborate chandelier. Another object that has become “visible” again in this way is a brick partition wall of several metres in height which also served as a podium and separated clerics from laypersons. “For me, this rood screen is a very exciting object. The written sources now help us identify exactly where it stood, when it was created, how it changed over time and what it was used for,” says Schedl. Every penny used for construction The altar is a religious item that frequently features in the construction history of St. Stephen's Cathedral. Towards the end of the 16th century, a total of 38 altars were mentioned according to Schedl. The altars fulfilled a dual function as liturgical objects and generators of funds.” As soon as a section of the building was roughly finished with a dirt floor and a temporary roof – in modern terms this would correspond to a building’s skeleton - an altar was set up. The services held there brought money into the church coffers. The funds were used to furnish the surrounding space, for instance to replace animal skins with glass windows or to continue building another section,” explains the art historian. In general, funding sources for construction were diverse, ranging from foundations and indulgences to bequests and fines for non-compliance with court rulings. The ruling classes contributed very little. Sustainable use of building materials Today we also realize how sparingly resources were used then. Everything from the pre-existing structure was recycled – this becomes clear from the fact that no items of expenditure for the removal of building material can be found in the treasurer’s accounts. The only exception was the annual removal of excrement from a small chamber in the tower. Unpaid work by volunteers on the construction site was also an important contribution. Throughout all social strata, such voluntary workers were mainly motivated by the thought of doing this work for their own salvation and because it was for a building dedicated to God. “In the last will of a poor widow I was able to decipher that she bequeathed her bedding and an old coat to St. Stephen’s. The treasurer’s accounts show that their sale raised a few pennies for the church coffers. That was touching,” relates Schedl. When Martin Luther's ideas began to take hold, donations stopped coming in - the North Tower has remained unfinished. There is now better evidence than ever before that throughout its three hundred years of construction, the Steffl, as it is fondly called by the Viennese, was funded and made possible by joint popular effort. No wonder the population feels such a strong bond to St. Stephen's Cathedral to this very day.

Personal details Barbara Schedl is an art historian and lecturer at the University of Vienna’s Department of Art History. Prior to this, she held positions at the University of California, Los Angeles at the Institute for Medieval and Early Modern Material culture. She has published a book on both research projects and has currently completed work on an online database, www.sanktstephan.at.

Publications