Self-portrayal as a source of knowledge

Humble stage sets, grubby costumes and make-up, actresses and actors with no literary background and forgetful of their lines: The many itinerant or “fleapit” theatres of the 19th and 20th centuries are not of great interest to research and have therefore hardly been explored. If one adopts another perspective, however, and looks at them from the point of view of the protagonists, they gain in importance. “They were very important to the actresses and actors themselves. For them, it was part of their professional profile to have spent a summer with a touring theatre and to have gained that experience,” says Katharina Wessely, an expert in theatre studies at the Austrian Academy of Sciences. At the time, the notion of honing one's skills by “doing the provinces” and actively experiencing all facets of the trade was an integral part of a collective professional identity, and the lowest level, such as a travelling theatre, was often an indispensable ingredient of an acting career. Wessely used an unusual source, i.e. autobiographies, to gain insights into the way actors and actresses saw themselves, their working conditions and the German-speaking theatre landscape.

Autobiographies construct truth

Recent autobiographical research has looked at these sources in the context in which they were created, recognizing that their “truth” does not lie in historically verified facts, but in the images they evoke. In her research project, which was supported by the Austrian Science Fund FWF, Wessely collaborated with the philologist Michaela Kuklová in looking at autobiographies as what they are: a medium which the leading figures use to construe a view of themselves, of the acting community, of their environment and of the German-speaking theatre scene. They analysed 30 autobiographies, including those of several well-known actors such as Gusti Wolf, Maxi Böhm and Paul Hörbiger. The selection criteria included, for example, whether they performed on stage in the interwar period of the 20th century and whether their acting activity covered a large geographical area. Wessely placed the main focus on the former Bohemian territories of the Habsburg Monarchy, which were regarded as a launching pad for acting careers.

The political context affects the view

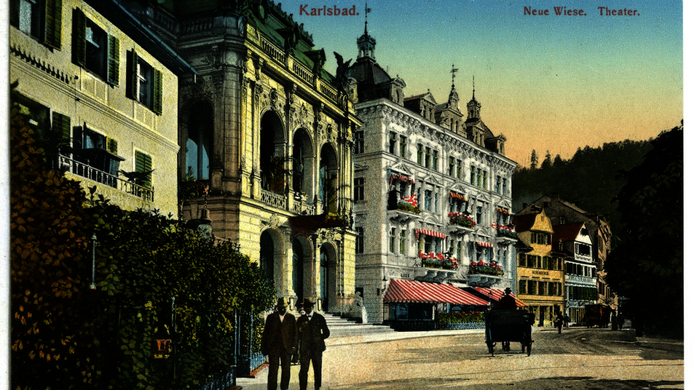

It turned out that all of those selected portrayed themselves in such a way as to tally with their public image, deliberately constructing a specific view. “In many cases one senses the artists making an effort to fit into the bourgeois work ethic. In the few female autobiographies we noticed that they also wanted to adhere to a middle-class understanding of a woman’s role as wife and mother,” notes Wessely. Something that made her analysis more difficult was the common practice of writing the autobiography in collaboration with a journalist. Wessely also chose the period before 1945 in order to find out whether the political upheavals then were recognizable in the texts, and she found a clue in the way the portrayal of provincial theatres changed. In the German-speaking theatre landscape, the term “province” referred to the size of the German-speaking audiences and the number of German-speaking theatres there, not the size of a given town. “Until 1918, the theatres in the Bohemian territories of the Habsburg Empire were regarded as provincial theatres. After 1918 they were part of nation states and the actors were then doing international stints. As of 1933, the German-speaking provincial theatres became important providers of work for those who emigrated to escape the Nazis,” explains Wessely. There were wide variations in how such flight is presented as part of an individual's personal history, ranging from a normal job change to a deliberate first step to emigration.

Dynamics made visible

Mobility was a common feature of acting careers in the German-speaking theatre world. The scientific analysis of the autobiographies revealed that this world comprised more than 200 stages. A special feature of this theatrical network is its dynamic evolution: theatres appeared and sometimes disappeared again, depending on whether they offered German-language plays or not. The theatre director played an important part in the dynamics, because, according to Wessely, “with every change of director the quality of a theatre and, thus, its status in the hierarchy was altered.” Wessely was surprised to note that the actors saw the large geographical space spanning half of Europe as very homogeneous. Where they played was less relevant to them than who the theatre director was. For this reason, the very same theatre can be a place that one wants to leave as quickly as possible in one autobiography and, at another time and under a different director, an ideal place to learn one’s craft. Autobiographies make these dynamics and evolution visible. In addition, the change of perspective can bring to light secondary aspects and heighten their relevance for further research. The autobiographies examined in this project have thus turned out to be valuable sources of theatre history.

Personal details Katharina Wessely studied film and media studies. She holds a position at the Institute of Culture Studies and Theatre History of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, where her research is devoted to the theatre and cultural history of the Bohemian territories in the Habsburg Monarchy. She places the main focus on cultural identity in terms of the professional profile of actors and actresses and on how this is treated in autobiographies.

Publications