Pointers by the Old Masters

For centuries, pointing gestures have been a common element in paintings. Linguistics calls them “deictic gestures”, from ancient Greek “deixis” for pointing or indicating. Renaissance painters – including Leonardo Da Vinci, Raphael and Michelangelo – and Baroque painters – such as Rembrandt, Rubens, Caravaggio and many others – deliberately employed pointing fingers to draw attention to significant characters in their pictures, highlight important symbols, and structure the images in terms of space or time.

Experts have always assumed that gestures achieve their intended purpose and contribute to a better understanding of pictorial content. French art historian Temenuzhka Dimova wanted to verify this assumption with scientific methods – and found the ideal conditions for her experiments in Vienna.

The codified language of hands

In the context of her doctoral thesis in France, Temenuzhka Dimova specialized in “the language of gestures in early modern paintings”. As she explains, “gestures have evolved into a codified system of hand signals with various iconographic meanings. If we know their meaning, the gestures explain to us what the characters are saying or how they are connected to each other.” But could hand signals also be understood intuitively, without any prior knowledge?

The Laboratory for Cognitive Research in Art History (CReA Lab) at the University of Vienna uses eye tracking to investigate questions like these. “The CReA Lab is the only eye-tracking lab I know that is run by an art historian (Raphael Rosenberg),” Dimova enthuses as she explains why she came to Vienna.

In the eye of art beholders

The project “Following the Festaiuolo: How Do Deictic Gestures in Painting Influence the Beholder's Gaze?” (2022–2025) received EUR 287,000 in funding from the Austrian Science Fund FWF.

Quantitative data for art history

A relatively new but increasingly popular method, eye-tracking is used in experimental art history, which is also growing in popularity. A special device records the pupil movements of individuals under controlled conditions while they view a work of art.

Some of the questions studied by the researchers: at what point does the viewing of an image begin, and at which areas do the eyes linger (“fixation”)? How does the eye move across the work (“scan paths”)? Between which parts of the image do the eyes jump back and forth quickly (“saccades”)? And to which areas do they keep returning?

The recorded eye movements create a wild zigzag pattern which provides quantitative data to test theories about the effect of images. Some of these theories are centuries old – such as the one positing that deictic gestures play a decisive role in helping us to better understand images.

A very special project design

Eye tracking can also be used to compare viewing habits in different cultures or among different groups of people. For her FWF project “Following the Festaiuolo: How Do Deictic Gestures in Paintings Influence the Beholder's Gaze?” Dimova worked with three such different groups:

First, with amateurs having no special art training (85 individuals); secondly, with art history students who approach a picture on the basis of specialist training (50 individuals); and thirdly, with deaf people who are fluent in sign language (30 individuals).

Why deaf people? “During my studies, I repeatedly worked as an art educator and came into contact with people who cannot hear,” explains Dimova. “I was fascinated by how they view images, and I wondered whether people who are trained to understand visual stimuli perceive images differently than normally hearing people.”

Dimova found this particularly interesting for images with deictic gestures, since gestures are the language of the deaf. “I am very happy that I was able to get Raphael Rosenberg on board to support this aspect in the project proposal,” she notes.

The untrained eye needs the pointing finger

All three test groups were shown a total of 16 paintings containing several deictic gestures on a large screen in the laboratory for 40 seconds each. After recording their eye movements, the test subjects were asked specific questions about the pictorial content to see how they interpreted the paintings.

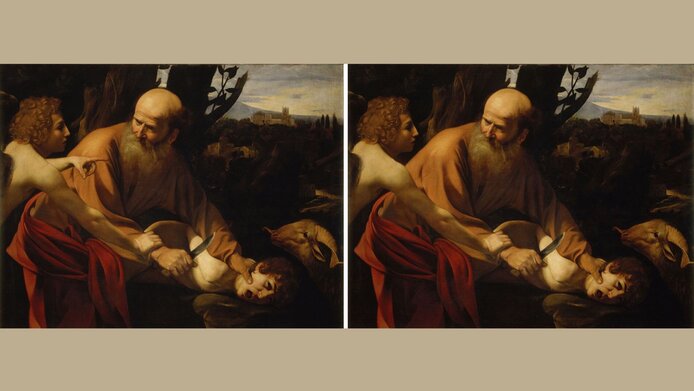

The group of laypeople was large enough for a second experiment: Dimova removed the pointing gestures from eight images using Photoshop. “In order to obtain reliable results, we had two sets of images: in one set, images 1–8 were edited, and in the second set, images 9–16.”

The researcher was surprised by how briefly the untrained subjects looked at the pointing finger. Nevertheless, that half second was enough to significantly influence the direction of their gaze and their understanding of the painting.

“We see that the subjects without art training tend to focus on smaller areas of the image, mainly faces and obvious pictorial elements, and that they explore the overall image less comprehensively,” says Dimova. “And in the edited paintings, they paid much less attention to the areas of the image that were actually relevant.”

Deictic gestures thus actually direct the (untrained) eye to essential content – as did the Festaiuolo, who gave his name to Dimova's project: a ubiquitous and well-known figure in 15th- and 16th-century theater, the Festaiuolo entered the stage to explain the plot to the audience. According to British art historian Michael Baxandall, painters of that time were inspired by this figure and introduced hand gestures to provide context and orientation for viewing the image, just like the Festaiuolo.

About the project

Old paintings in particular often show people pointing at something. Temenuzhka Dimova and Raphael Rosenberg from the Cognitive Research in Art History Laboratory (CReA Lab, University of Vienna) used eye tracking to examine whether pointing gestures actually direct the gaze and whether they influence the information that viewers glean from the painting. They found differences between lay people, art history students, and deaf people who communicate daily using sign language.

Deaf people as attentive as art students

Compared to the lay group, art history students and deaf people (even without prior art history training) were significantly more interested in image details: they studied larger areas of the paintings, were notably faster and explored more eagerly.

The eye-tracking results confirmed Dimova's assumption that deaf people are more sensitive to visual details in paintings due to their training in visual perception and their education in a “3D” language – i.e. sign language. “They view images in a similar way to people who know exactly what is important in a painting,” says Dimova. Like the art history students, they paid attention to details such as relevant gestures, significant objects or faces, and were subsequently able to describe and interpret the paintings better than the lay viewers. Dimova regrets that this third group was not large enough to test the difference between original and edited images.

At any rate, the researcher would like to expressly encourage deaf people to engage with the visual heritage of the human race: to study art history, work as guides for deaf people in museums, curate exhibitions – or, like Dimova, explore what images have to tell us. “They have very special abilities in this regard.”

About the researcher

Temenuzhka Dimova studied art history in France. In her doctoral thesis, “The Language of Gestures in Early Modern Paintings,” she analyzed the codified pictorial and sign language in European visual cultures of the 16th and 17th centuries. Working as a museum guide brought her repeatedly into contact with deaf visitors, which sparked her interest in whether deaf people pay attention to different things than hearing people. Together with Raphael Rosenberg, Dimova developed a project design that involves deaf people in eye-tracking experiments.

Publication

Brief glance, lasting effect: How pointing gestures influence the perception of paintings, in: Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 2025