"Only those who fail can progress"

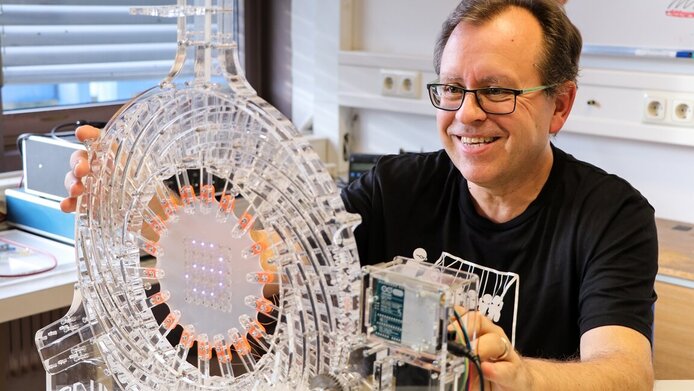

If you enter his laboratory you won't see any expensive high-tech equipment right away. Instead, there is any amount of Lego toy bricks, plastic film, a drain pipe, a “Lego-based stretcher”, a laser cutter and a 3D printer. “We also use balloons. If you work like this you are looked at, of course, as very provocative! After all, physics is regarded as being difficult and incomprehensible, so how could physics research possibly take inspiration from things as humdrum as that”, says Siegfried Bauer in the interview with scilog, adding: “My people are extremely successful in Japan and the USA with their ‘toys’!” – It's no wonder “playful” is a term his colleagues tend to use when commenting on his working methods.

From kitchen to top journal

In his research, the university professor and head of the Soft Matter Physics (SoMaP) Division at the Institute of Experimental Physics, Johannes Kepler University Linz (JKU), deals with highly topical issues such as electronics on curving surfaces, flexible and concealed electronics that can be attached anywhere, but also artificial muscles. Bauer is convinced that 20 to 30 years from now we will be just as familiar with electronics in our clothes, on our skin and even in our bodies, as we are with tablet computers and smartphones today. Among the things he works with are elastomers, such as one can buy in DIY stores as window sealants, or kitchen plastic film. Doing so also gets him on the cover of top journals, since his work is seen worldwide as trailblazing in the area of macroelectronics. In his research, he combines applied mechanics and physics with electrical engineering in order to create the hardware for the Internet of Things.

Electronics one can crumple up

One of the members of his team is Martin Kaltenbrunner, who returned from Japan to the SoMaP in 2014 and acquired academic habilitation status in 2016. Kaltenbrunner has managed to apply electronic circuits to an extremely thin film. The film is 27 times thinner than paper and can be stretched and even crumpled without damaging the circuits. There are many possible applications for this development. The electronic foil could, for instance, be attached to dentures for quadriplegics. Touching them with the tip of the tongue could trigger electrical impulses and thus control devices that quadriplegics would not be able to operate otherwise.

Ultralight solar cells

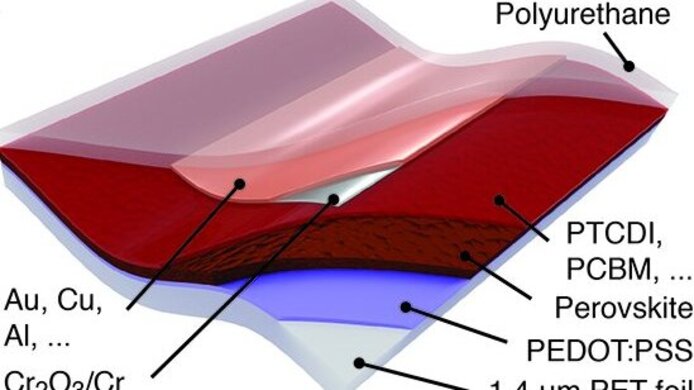

The world’s thinnest air-stable perovskite solar cells were another highlight. It took an ostensibly simple idea to achieve that breakthrough: chrome-plating protects electronic devices and gives them an expensive looking finish. In the solar cell, an ultra-thin layer of chromium and chromium oxide between the semiconductor and the electrode fulfils the same purpose.

Physicist, writer, entertainer

Being someone who habitually thinks outside the box himself, Bauer mainly attracts young people eager to venture forth and break new ground. Siegfried Bauer is a man who questions everything, because he believes that indeed a scientist needs to question everything. In his lectures he may well irritate new students by reading out a statement from a book and then demonstrating the exact opposite in an experiment. For some people that may be unsettling, but others are enthralled by this quality. “A good physicist is not merely a physicist. He is also a writer, because he has to tell a good story. He is an artist, because he needs good images to put across complex information in a simple way. And he’s an entertainer, for he has to draw people in. Please make sure you learn this right at the beginning!” Bauer advises his students.

Simplicity does it

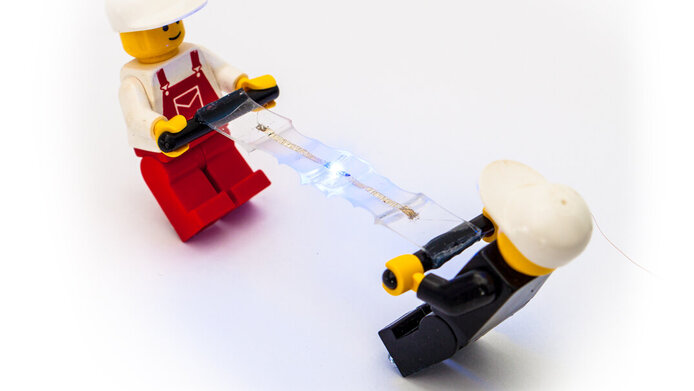

How can you best convey scientific outcomes that are hard to understand? Stretchable electronics? – By two Lego figures pulling apart the soft circuit material. The world’s thinnest air-stable perovskite solar cells? – By an ultralight solar-cell powered model plane circling over the campus. These are only two examples of images that got the scientists from Linz on to the covers of Advanced Science and Nature Materials. In order to make good photos, the team will spend a few days working on the set-up. For this purpose, Bauer has installed a small “photo studio” at a laboratory. In this respect, too, the man who loves the comic strips of Carl Barks and Don Rosa opts for simplicity. Given that such an approach teaches his students to address seemingly simple and yet profound scientific issues at the border realm between physics and engineering, it is no wonder that Siegfried Bauer’s scientific work is getting so much attention in the international expert community.

Thinking outside the box

The 55-year-old scientist is used to raising hackles and did so already during his days as a doctoral student at the University of Karlsruhe, when he wrote a provocative preface to his thesis and added a few cartoon drawings. Realising the talent of the young man early on, his supervisor staunchly supported him - even against resistance from other examiners. “I would go through thick and thin any day for my PhD supervisor”, Bauer declares fondly.

“Being clueless is a great driving force”

The university professor interprets his own remit as a mentor by judiciously guiding the people around him so as to help them arrive at their own ideas and own projects as quickly as possible. Each of his doctoral students has what they call a “flagship project” for which they are personally responsible and for which they set up their own teams. Beyond that, the students are free to participate in any other project if they believe they have something to contribute. Creativity and courage are the qualities that Bauer considers most important in his co-workers. This is the advice he most frequently gives: “Don’t trust the old guys!” The recommendation is inspired by his own personal experience of becoming more cautious with age. “Having no clue is a great driving force in science, and the older you get the less clueless you are, and the less bold you become.”

Associate Editor and IEEE Fellow

This is also why, in his capacity as associate editor of the journal Applied Physics Reviews, Bauer frequently proposes for reviews young people he considers as promising and not the “old guys”. He loves to attend conferences and lectures on a wide variety of topics. “If a lecture appeals to me I talk to people, and if the fascination persists I will put them forward”, he recounts. At the beginning of the year, Bauer was appointed an IEEE Fellow, a special membership status at the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, awarded to individuals of extraordinary merit in any of the spheres of interest of the IEEE. In answer to the question at a faculty meeting as to why he received this award, he replied “It’s simple: show commitment to them for many years without ever worrying about ‘making it’, and suddenly it will happen.”

Firmly grounded

Siegfried Bauer probably inherited this down-to-earth attitude from his family. Raised as the youngest of four sons at a small side-line farm near Karlsruhe, he considers mutual support to be a given. The family had no academic background whatsoever, as is well illustrated by the following story: when Siegfried Bauer was a student of physics in Karlsruhe, a professor came to see him at his home. His mother, a down-to-earth housewife, was so in awe of the scholar that she kept herself “busy” up in the attic the whole time he was there. “We still joke about it today. Whenever I come home I say to her ‘Please don’t feel you have to hide up in the attic for my sake!’”, Bauer smiles.

The love of mathematics and physics

The youngest son of the family developed a love of reading because of his frail health which meant he could not pitch in as much as the others with the work at the farm. A stay in hospital for several months forced the 16-year-old into immobility and led him towards mathematics and physics. He asked his mother to bring him books so he could keep his mind busy. Whereas he had been a mediocre pupil in these subjects before, the months of hospitalisation brought radical change in that respect. Moreover, when he returned to school, there was a new, very committed physics teacher, and Bauer attended a specialised course in that subject. “That was great! Once a week we had all the equipment completely at our disposal. The teacher would say ‘Think of a project and I will help you with it’”, he passionately recalls.

Balloons and magnetic balls

That is exactly the type of classroom instruction that Siegfried Bauer would like to see more of at schools: less rote learning and more critical questioning. “There are no simple answers. Teachers, in particular, need to think critically”, postulates the father whose two children are at secondary school. This is why he tries to demonstrate in his teacher training that a theorem may be correct and incorrect at the same time. Using hands-on examples he shows the teachers experiments that intrigue children using very simple means: balloons, beer coasters or a magnetic ball dropping very slowly through a roll of aluminium film.

Accepting failure

More freedom and more daring is what Bauer would like to see in the education system and in science. “The system needs to tolerate lateral thinkers and support them instead of perceiving them as a nuisance”, he explains. He puts particular emphasis on accepting and integrating failure. “If I had not failed several times I wouldn’t be successful”, he declares with conviction. Some of his students are baffled when they go to see him and are not given a clearly defined problem, nor a method – just an open question. One of these questions gave rise to the development of the first stretchable battery - the result of a project supported by the Austrian Science Fund FWF.

Concealed electronics

Since 1998, Siegfried Bauer has received a total of 10 grants from the FWF, and in 2011 he was awarded one of the internationally coveted ERC Advanced Grants. He is currently writing research applications on the topic of “concealed systems”. “Electronics can be successful only when they are not visible to people, when you are able to operate the most complex device without having a clue as to the technology behind it”, says Bauer. Recently, his research team has been working a great deal with paper. A possible application would be a humidity sensor for walls – painted over and invisible – which communicates with a smart phone via Bluetooth and sends a warning when the wall gets too damp. The system could also be connected to a dehumidifier, sending it exactly the information it needs. Another area of application: a paper sensor with reusable electronics attached to a diaper which reports when the diaper is full. While the paper is disposed of together with the diaper, the electronics can be reused. In nursing homes, such a system could considerably reduce the amount of waste generated.

“You’re collecting junk!”

One of his private passions is collecting old steam radios. “Each of my 20 radios has a special feature, relating either to its casing or the design”, Bauer enthuses. Since the scientist collects only exotic brands, such as the Austrian Hornyphon, he gets them “for peanuts” at flea markets. He takes the ancient radios apart and now and then uses one of them in his lectures. Some of the items he had no room for at home are stored in his office. The comment of his wife, also a physicist at the Institute: “You’re collecting junk!” But who knows what this “junk” will lead to one day?

Siegfried Bauer is a Professor of experimental physics at the Johannes Kepler University Linz (JKU) and the head of the Soft Matter Physics Division (SoMaP) at the department of experimental physics. After receiving his PhD at the University of Karlsruhe he started as a scientific assistant and project manager at the Heinrich Hertz Institute in Berlin. In 1995, after research stays in Montreal and Washington, he attended the University of Potsdam to acquire his academic habilitation. In 1997 he was appointed professor at the JKU. In addition to other high-ranking scientific awards, Bauer was awarded an ERC Advanced Grant from the European Research Council in 2011 and has been an IEEE Fellow since the beginning of 2016. Bauer is the father of two children.