Of complex molecules and surreal animals

Molecular physicists try to understand complex chemical processes at the atomic level. Accordingly, they are neither chemists nor physicists, and yet they combine a bit of both. After studying chemistry in Berlin and Madrid, I completed my PhD in molecular physics in Innsbruck and now work as a Schrödinger Fellow at the Department of Physical Chemistry at the University of Melbourne. In recent years, I have developed a growing interest in studying and verifying inter- and intramolecular chemical processes at the microscopic level.

One molecule, many aspects

Many molecules of a certain mass come in different structural arrangements, which are also known as isomers. Transformations between these stable structures play a crucial role in a variety of natural and technological processes such as the chemical evolution of the universe, plant metabolism or the generation of solar energy. In order to investigate such transformations, researchers need new methods that can efficiently separate individual isomers and analyse the impact of external impulses on their shape and reactivity. Evan Bieske has developed just such a device at the University of Melbourne. In his research group, I embarked on a fascinating adventure almost two years ago.

More information

Platipus built, Platypus discovered

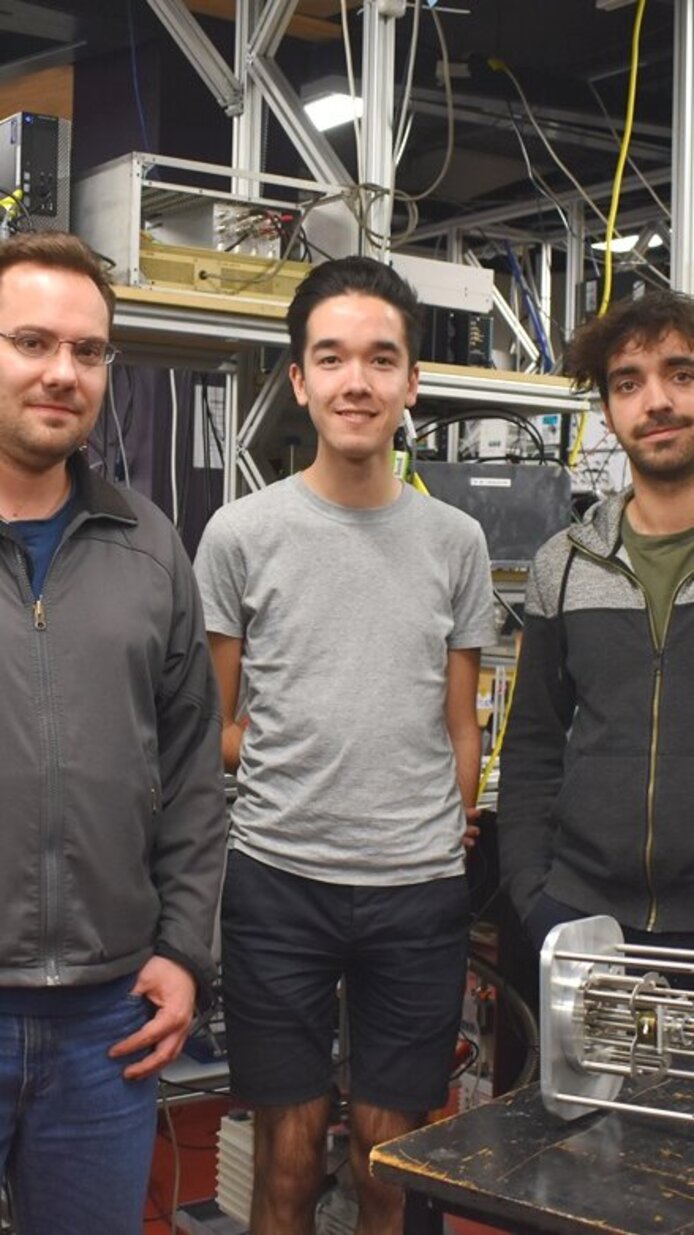

One of the things I discovered here in Down Under was my new favourite animal, the Australian platypus – a weird mixture of duck and beaver. Of course, it stands to reason that such a strange animal is to be seen extremely rarely, which is why I decided to build my very own complex Platipus (Probe of Laser Ablated Trapped Isomer Photochemistry Using Spectroscopy). The real scientific motivation behind my project in Melbourne was the possibility of building a new machine that could separate isomers, cool them down and examine their structure. Developing and implementing such an instrument confronted me with a huge and time-consuming challenge. In the course of it, I also came across difficult aspects of the Australian science world in my field, the natural sciences, such as long delivery times and understaffing in the electronics workshop. But, as is often the case, everything has two sides, and these obstacles taught me to solve problems that involved the need for minor technical and electronic tinkering by doing it myself. In the end, not only the molecules we examined but also our laboratory have transformed gradually, and the Platipus is now ready. – Incidentally, I even managed to catch sight of a real platypus after many trips into the wild. Having achieved both of these goals is maybe a sign that it will soon be time to return home.

History and skyscrapers

The University of Melbourne is Australia's second oldest university, situated just a few steps from the skyscrapers of the business and financial hub. The relatively compact university campus with its beautiful old British style buildings is an oasis of knowledge and peace in the middle of the big city. There are good coffee shops (a plus), no student cafeteria (a minus), and lots of student events, farmers' markets and barbecues with colleagues. Moreover, the bicycle path network in Melbourne in general and around the campus is more than acceptable for a big city and provides an efficient means of transport to avoid traffic jams. All in all, Melbourne is a cultural metropolis where development never stops. It is definitely a city to be recommended.

‘No worries’ in the land of never-ending natural wonders

Yes, life outside the laboratory is definitely possible, and it is an absolute must in Australia! This is why at the beginning of my stay my family and I bought an old car and have tried to see as much of the continent as possible. We enjoyed the very friendly Australian atmosphere, learned a great deal about the ancient, varied history of this huge country which is bound up so much with nature, and of course we also saw unbelievable rainforests, lonely beaches and a great variety of surreal animals. Being in Australia was incredibly enriching for me and my family. So much so, that our second child is an Australian-born wombat. This time was definitely an “upside-down” experience of life for us and some of our molecules will remain here forever. – My thanks go to the FWF, Evan Bieske, James Bull, the whole research group and the mechanics workshop, with all of whom I shared many convivial moments.