Nasal spray against drug death

Academy Award winner Philip Seymour Hoffmann, pop legend Prince, US musician Tom Petty, three show business luminaries with the same cause of death: an overdose of opioid painkillers. This is a problem that affects not only the music and film industry, but all strata of American society.

Painkillers as a gateway drug

It quite commonly starts with a sports injury, a sore tooth or back pains. The doctor will prescribe an opioid-containing painkiller that quickly relieves the pain – and makes the user dependent. This is a seemingly harmless way of becoming addicted to drugs. According to estimates by US authorities, there are over two million opioid addicts in the country. The CDC reported the number of drug-related deaths in 2019 at around 71,000. Every single day, almost 200 people die in the USA from overdosing on opioids – including heroin, methadone, fentanyl and prescription painkillers. The opioid epidemic is now the leading cause of death among US citizens under 50.

It all started with the miracle pill

1996 marked the beginning of the first wave of the opioid crisis, when the US company Purdue Pharma launched the prescription painkiller OxyContin and for years marketed it as being completely safe. This drug provided quick, seemingly harmless relief for many pain patients. It was also attractive for health insurance companies because the drug was cheaper than long-term therapies. Between 1991 and 2011, the aggressive marketing of the alleged miracle pill by the manufacturers and the eagerness of doctors to prescribe it led to a tripling of prescribed painkillers in the USA, from 76 million to 219 million per year. The consequences were devastating, since the synthetic opioids contained in the drugs are not only effective against problems such as pain and anxiety, but they also very quickly induce addiction.

From painkillers to heroin and fentanyl

As prescribing practice became more rigorous and the pills became too expensive on the black market, many people who were addicted switched to cheaper semi-synthetic heroin and, in recent years, increasingly to the completely synthetic opioid fentanyl. This was another fatal development: fentanyl is 50 to 100 times stronger than morphine, which increases the risk of a fatal overdose due to respiratory failure. Given that the production of fentanyl is relatively simple and that its high potency enables dealers to rake in large profits with comparatively small amounts, the substance is also mixed into cocaine and methamphetamines. As a consequence, drug users are sometimes not even aware that they are at risk of overdosing. A famous and sad case in point: the US musician Prince, who died in 2016 from an accidental fentanyl overdose.

National emergency

After fentanyl had ominously and triumphantly conquered the US drug market in 2013, the number of overdose deaths continued to rise in the following years. The opioid crisis took on such proportions that President Donald Trump declared a national medical emergency in October 2017: in that year, 47,000 people died as a result of an opioid overdose, which is the equivalent of 130 deaths every day.

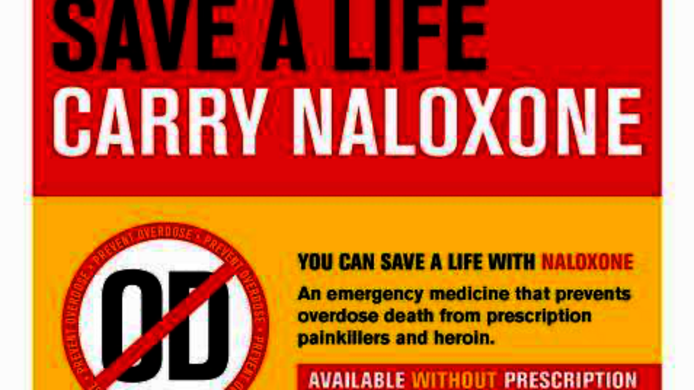

Overdose reversal with naloxone

Naloxone is a substance that is used as an emergency treatment for opioid overdosing. As an opioid antagonist, naloxone blocks the opiate receptors in the brain. It was patented in New York in 1961 and has been used since 1971. In cases of respiratory arrest, it works within seconds and can be administered intravenously, intramuscularly or as a nasal spray. For a short time it cancels the effects of opioids and thus prevents damage to the central nervous system and death.

Lifesaver training

In 2005, some US cities – most prominently New York City – began distributing naloxone kits to the population free of charge as a first aid measure, including training. Anyone can attend such training and will receive a naloxone kit, enabling them to save lives in emergencies. Such training sessions are attended not only by people who are themselves affected by an addiction, but also by their relatives, police officers, supermarket employees and staff of organisations that help addicts.

Heroes of everyday life

“Almost everyone here in New York who uses opioids is aware of naloxone and my estimate is that 70 per cent of them have received training and a naloxone kit,” says Laura Brandt, a psychologist from the University of Vienna. Her research explores how effective these prevention programmes are and what factors come into play. In February 2019, she relocated to Columbia University in New York under an Erwin Schrödinger Fellowship for research abroad from the Austrian Science Fund FWF. She reports that both knowledge about overdose prevention and the acceptance of the programme are very high there, partly because of the way this measure is communicated. “Being able to help in an emergency gives ordinary members of the public a sense of self-efficacy. And this is exactly the way the NYC Department of Health communicates the measure: You are a heroine, a hero of everyday life,” notes Brandt, who sees something archetypically American in the hero-focused approach. “Hero status and the knack of how to advertise are embedded in American culture.”

What makes an intervention programme successful?

The organisations offering these training courses do so on the basis of well standardised training protocols, which were developed by scientists and lab tested for their efficacy. Nevertheless, they do not always work in practice. Finding out why they fail is exactly what implementation research is all about. The 35-year-old Brandt calls it “taking a look into the black box”. According to Brandt's experience, success depends on two factors: one is implementation fidelity, i.e. whether trainers adhere to the protocol, and the other is acceptance, i.e. whether both trainers and trainees consider the training to be useful and important. “If you ignore this when implementing intervention programmes, you will always have to wonder why they don’t work,” Brandt says.

The first steps in an emergency

At just four pages, the naloxone training protocol is short and simple, making it easy to use and evaluate. The first part of the training deals with how to recognise an overdose. The cause of death in that case is respiratory arrest, which is relatively easy to identify: no breathing, blue lips, blue fingernails. But even if the person who is lying on the floor had a heart attack, you cannot do any harm with naloxone, because it only works on the opiate receptors. If there are no such substances in the body, naloxone simply has no effect at all. So if you see someone who shows signs of overdosing, you should call 911 and administer first aid with naloxone. A crucial aspect is the existence of a law that says that first-aiders who are carrying drugs cannot be prosecuted for that. “Nobody will call 911 if they have to worry they might be arrested,” says Brandt.

Train-the-Trainer programme

The NYC Department of Health offers two-hour train-the-trainer courses which provide additional background information and authorise attendees to organise trainings and dispense naloxone themselves. “This programme is very well implemented; they keep it simple and realistic and at a low cost for the organisations,” notes Brandt in assessing the prevention efforts of the New York Department of Health.

Field research

Brandt chose New York as the venue for her research because the city has 15 years of experience in this area. The first results of her work show that the organisations have succeeded well in firmly establishing the prevention programme, since both intervention fidelity and acceptance are very high. The first step in her research is to gain the organisations' trust so that she can move around in their premises and watch people at work. “As a double alien – a researcher and a German/Austrian – it took a few meetings for me to be let in,” she says. Once the first step has been taken, the psychologist conducts extensive interviews with those in charge of the naloxone programmes to find out what the plans were like at the beginning, what changes were carried out, and what support the trainers as well as the organisations themselves receive. Then comes the collection of data, where Brandt explores factors such as knowledge gain and acceptance.

Corona hotspot New York City

That was precisely the phase the researcher had reached at the beginning of March 2020, when the corona-related lockdown came and she was ordered into home office. In the spring, New York was the US corona hotspot with rapidly rising numbers of infections and deaths. “For me, the worst moment was when tents were put up in the city centre to store the bodies because the morgues were full, and when there were discussions about whether temporary graves should be dug in parks,” Brandt recalls when thinking back to the moment when the city held its breath.

Herd immunity in New York City?

Brandt, a native of Heidelberg, feels unable to assess whether quicker action on the part of policy makers would have prevented corona deaths, as there is still too little knowledge about Covid-19. Moreover, she feels, one has to keep an eye on the order of magnitude: “New York City has as many inhabitants as the whole of Austria. The USA is not only very large, but it also exhibits vast regional differences. In New Jersey, the place I recently moved to, people are all compliant and wear their masks. In Washington Heights they wear them too, but on the chin,” she smiles. “The population density of New York City makes it impossible to introduce efficient distancing measures.” Since there was a clear peak and then a clear drop in infections, Brandt has a theory: “New York City is probably the closest to herd immunity in the world.”

Wearing masks for the heroes

Even though there were protests in the USA against the measures to contain corona, many people could be motivated to comply. Brandt sees a big difference compared to Europe in the way this is done. “People who work in essential community jobs, such as in health care or waste collection, have acquired hero status. People say to themselves: it is for these heroes that I will wear the mask and wash my hands. Around here you cannot say to people ‘just do what you are told’. The outcome is the same but the motivation is completely different,” says Brandt in describing the cultural differences. This is precisely the hero status that you also acquire when you save someone from death by overdose.

Effect of the lockdown on prevention work

By the time the lockdown began, Brandt had already collected a large amount of the data she needed, but the unexpected events raised new questions. The researcher plans to conduct a subsidiary study to investigate how the lockdown affected prevention programmes. Firstly, the programmes could not continue as before, and drug use also changed because people had no other option than to take what they could lay their hands on. “This can lead to a higher consumption of drugs that are mixed with fentanyl, which increases the risk of overdosing,” says Brandt. And there was a second effect of the lockdown that she experienced in interviews: some people with addictions experienced the self-isolation as helpful, because it reduced the pressure to integrate socially and all doctors could be reached online. According to the original schedule, her research stay was planned to end in February 2021. But in order to be able to pursue all these new questions, Brandt would like to extend: “I believe this is an important moment from which we can learn a lot in both the USA and Austria.“

Synergies with addiction aid project in Graz

When Brandt returns to Vienna, she would like to contribute her experience to an addiction aid pilot project in Graz, at the Caritas Kontaktladen. “The synergies are extremely high! The protocols from New York can readily be used in Austria and we can bring together my experience from the USA and that of Graz,” she says. What we in Austria can definitely learn from the Americans is marketing. “We should learn from them how to communicate measures efficiently, so as to reach people who are not per se interested in the topic. You will hardly meet anyone on the streets of New York City who does not know about naloxone.”

Personal details

The psychologist Laura Brandt is currently a postdoctoral research fellow at the Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University, New York City, on an Erwin Schrödinger Fellowship funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF. The German native studied psychology at the University of Vienna and received her doctorate in applied medical science at the Medical University of Vienna. She worked in the clinical field at the Geriatriezentrum Wienerwald and at the Schweizer Haus Hadersdorf, an institution for inpatient and day-patient therapy for addiction disorders. Her main research areas are studies on substance use disorders and their concomitant diseases, opioid substitution therapies, especially for pregnant women, as well as socio-economic/political and gender-specific aspects of addictions. She adopts an implementation perspective in order to make a long-term contribution to improving addiction treatment and “harm reduction” approaches (such as the provision of naloxone).