Migration leading to world power

The history of Ancient Egypt extends over several millennia from the pre-dynastic period around 4000 BC to the year 395 AD which marks the end of the Greco-Roman era. Egyptian history is divided into 31 dynasties, some of which ruled simultaneously in different parts of the country.

Rulers of the foreign lands

The Hyksos, a people that was not of Egyptian origin and dubbed “rulers of the foreign lands” by the indigenous Egyptians, established their realm in the eastern part of the Nile delta. Since only sparse written records have survived from that period, the world knows little about the Hyksos dynasty, which ruled between 1640 and 1530 BC. Where did these “foreigners” come from? How did they come to power and what caused their downfall? These are the issues Manfred Bietak has been investigating for almost half a century.

Mediterranean Metropolis

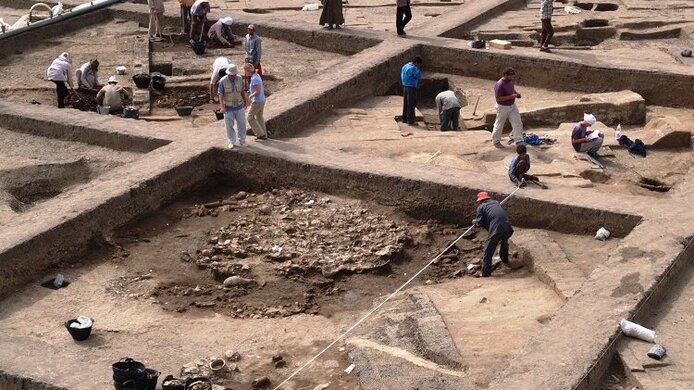

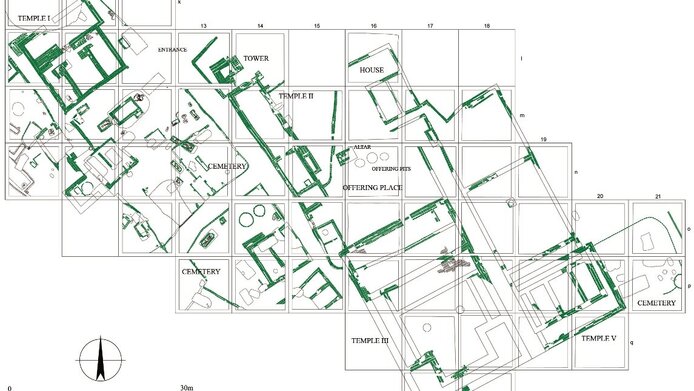

Back in the late 1960s, the Viennese Egyptologist discovered Auaris, the capital of the Hyksos realm, near the modern-day village of Tell el-Dab’a, about 140 kilometres northeast of Cairo. Boasting some 30,000 inhabitants, it was the largest city of its day in the Mediterranean region and a hub of international commerce. In recent decades, archaeological digs have supplied a huge amount of data about the population during the Hyksos rule, providing insights into the type of settlement it was, the architectural details of the palace and temples, funeral rites and general cultural aspects.

An Award by the ERC

Advanced Grants by the European Research Council (ERC) are endowed with up to 2.5 million Euros. In 2015, the ERC awarded such an Advanced Grant to Manfred Bietak for his project “The Hyksos Enigma”, in which the scientist pursues mainly questions of historical interest, such as the origins of the Hyksos, their ascent to power and their influence on other parts of Egypt.

From migrant workers to the elite

Bietak has found many indications for the Hyksos having come to Egypt from the northern Levant. “Initially, they were migrant workers, if I may call them that, presumably sailors, ship builders, mercenaries and traders.” Not only was their knowledge very useful to the pharaohs, but the immigrants also brought new customs, cults, architectural designs and working animals – such as the horse, which also played a part in new methods of warfare. They introduced the Acadian language for diplomatic communications, traded in cedar wood, wine and olive oil and brought innovative technologies for metal processing and the production of ceramics to their new home. Ultimately, the Hyksos managed to rise to the level of a political elite. “The migration of this people from the Near East to Egypt and the combination of the know-how of both nations turned Egypt into the global power in the region”, observes Bietak, professor emeritus of Egyptology at the University of Vienna.

Reading bones

Manfred Bietak pursues a multi-disciplinary approach, supplementing his archaeological and historical research with methods from biology and geo-chemistry. “Advances in archaeological research are greatest when you opt for a multi-disciplinary route”, emphasises the scientist in his interview with scilog. Bietak co-operates, for instance, with the bio-archaeologist Holger Schutkowski from Bournemouth University in the UK, who subjects human remains to isotope and DNA analyses. Other elements that supply further knowledge about the Hyksos are text analyses, architectural features, the study of religious rituals and funeral customs as well as of material culture. In addition, Bietak looks into the trade relations of the “foreigners” with Western Asia, Cyprus and Nubia (located in modern-day Sudan), as these relations were also instrumental in the rise and decline of their realm. Bietak is certain about one thing: “The Hyksos played a much greater role in the history of the Old World than hitherto assumed. The great achievements of Ancient Egypt in combination with the expertise of the immigrants from the Levant were probably the secret of Egypt’s success in rising to the status of a world power.”

“Certain events repeat themselves”

There is an adage saying one has to know the past to understand the present. Bietak tends to agree. “Certain events repeat themselves. Ancient history also knew massive flows of migration, and this is something we are seeing today. I assume that 50 years from now a considerable share of the European population will have oriental roots. Perhaps one can hope that people will become acculturated and contribute to a successful Europe of the future”, he notes.

Radicalisation and western interventions

According to Bietak, the radicalisation to be observed in western Asia today is mainly a consequence of interventions from the West: “Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria. As far as these countries are concerned, I am not optimistic. The interventions by the major powers have wrought havoc with local power structures. Brutal though these regimes may have been in parts, they maintained a sort of equilibrium. Now the structures are collapsing, and a variety of groups and interests are coming to the fore. If there hadn’t been the intervention in Iraq, developments such as IS wouldn’t have occurred”, runs Bietak’s analysis. The scientist had earlier seen signs of advanced secularisation in countries such as Iraq, Afghanistan or Egypt. He considers radicalisation to be a defensive reaction to overpowering influence from the West. “The West behaved like an imperial power. People don’t like that. They have revived their own traditions and have become more religious again. Persia, a country that was secularised to a large extent, also returned to strict observance of Islam. The urge of western powers to play world policeman has contributed to a fateful development”, the researcher notes with conviction.

It all began with the adventures of explorers

Manfred Bietak’s interest in the ancient history of Africa began when he read about the adventures of explorers as a child. Early on in his studies at the University of Vienna he was given the opportunity to take part in archaeological digs in Nubia, and within a few years he was in charge of the site. “Over time I must have conducted something like 80 excavation and investigation campaigns in Tell el-Dab’a that unearthed a wealth of new findings”, Bietak recollects.

Bologna corsets studies

He regrets that the students of today do not have the freedom to take their time and spend several months at excavation sites. “In my day, the best students usually took longest to finish their studies. They would not be satisfied unless their thesis was simply fantastic. This was their qualification ticket for the international market. The strict corset Bologna has

introduced on study courses is a disaster!” Bietak would like to see the Bologna system abandoned at university level – in combination with the introduction of aptitude tests. “That is the secret of success at famous universities such as Harvard and Yale: every candidate has to undergo an interview. Not everyone is qualified for every course of study.” Moreover, the institutes must not be pressured to enrol more students by the threat of being merged. “Wanting to create the largest possible institutes is madness anyway! Particularly in the more ‘exotic’ programmes, we must foster small institutes and enable them to have a research output that can stand up to the big ones. In the study courses with great masses of students, there is powerful international competition. Research policy makers need to consider in which fields we can gain a high profile”, he insists.

“Vienna is THE centre of Egyptian archaeology”

The developments in his own speciality confirm his views. “Today, Vienna is THE centre of Egyptian archaeology in the academic world”, Bietak notes. The foundations were laid by Bietak himself and his staff. “But my predecessor Dieter Arnold and my successor Christiana Köhler also contributed their share”, he adds. Bietak is very grateful to the Austrian Science Fund: “The FWF has been a great help for me. Particularly the special research programme SCIEM 2000 permitted me to recruit many young colleagues from archaeology and Egyptology.” The funds from this Special Research Programme (SFB) enabled Bietak to set up an entire department at the Austrian Academy of Sciences (ÖAW) – the Commission for Egypt and the Levant. “I had many excellent students. Most of them now work very successfully in Austria and elsewhere in the field of Egyptian archaeology”, he adds not without pride. Resulting from this undertaking are about 80 monographs published in the context of the ÖAW and 25 volumes of the internationally very successful journal Ägypten und Levante/Egypt and the Levant.

The problem of age discrimination

One aspect the 75-year old appreciates particularly about the activities of the FWF is the lack of any age discrimination. “In the USA you yourself decide when you go into retirement. Here in Austria you can’t do that”, he complains and goes on to explain that academics reach their peak late in the humanities because experience is of such vital importance there. Also, the heavy administrative burden limits research activities during the researchers’ active years and they tend to postpone many endeavours till pensionable age. “But if you retire you run the risk of being side-lined”, Bietak notes with some irritation. This is why he particularly welcomes the fact that neither the FWF nor the ERC discriminate researchers on the grounds of age and allowed him to continue his career. The fly in the ointment for the untiring scientist: “Ever since I received the ERC Award I'm being deluged by a wave of problems.” But he is certainly not one to succumb to resignation.

Manfred Bietak acquired his doctoral degree in Egyptology at the University of Vienna in 1964. From 1966 until 1969 and from 1975 to 2009 he was head of the archaeological excavations in Tell el-Dab’a in the Eastern Nile Delta. In the process, Bietak identified the Hyksos capital Auaris and the Ramses city Piramesse. In 1971, he built an archaeological research centre in Egypt which was incorporated into the Austrian Archaeological Institute (ÖAI) in 1973 as its Cairo Branch and headed by Bietak until 2009. Until his retirement in 2009, he was professor of Egyptology at the University of Vienna and, as of 1986, head of the Institute of Egyptology. Between 2004 and 2011, Bietak was the Director of the Vienna Institute of Archaeological Science at the University of Vienna. Besides numerous distinctions and honours, Bietak was awarded one of the most prestigious international distinctions in 2015: an ERC Advanced Grant. The European Research Council awards this grant to only 5 to 10% of the projects submitted by top scientists.

More information