Photographer Jovan Ritopečki documented the lives of Yugoslavian migrant workers in Austria. His extensive estate from 20 years of photographic history (1970-1989) has now been subjected to a first study by historians.

Labor migration captured in empathetic images

In 1966, Austria concluded a recruitment agreement for workers from what was then Yugoslavia, following the model it already had with Turkey. In the following years, hundreds of thousands of people responded to the call and became what were then called “guest workers” in Austria. 1966 was also the year in which Jovan Ritopečki left Belgrade for Vienna. Born in 1923, he became self-employed as a photographer in the early 1970s and worked for Austrian and Yugoslavian magazines that catered to migrant workers. One of the few photographers to produce professional visual documents of the life and work of migrants in Austria at the time, Ritopečki offers an unparalleled perspective on his fellow Yugoslavs who had migrated here.

In the project “Picturing migrants’ lives”, set to run until 2025 with funding from the Austrian Science Fund FWF, the historian Vida Bakondy makes it her task to process and to some extent digitize Ritopečki's photographic work. Bakondy discovered the extensive estate of Ritopečki, who died in 1989, at the home of one of his daughters and is now processing it in the context of “visual culture studies”. “A large proportion of Ritopečki's works deal with migrants’ work environment, but they also provide many insights into their private circumstances,” notes Bakondy. “He captures people in their sleeping quarters or during leisure activities. The documentation of living conditions in particular also involves a socio-critical dimension.”

Given the sheer volume of images that the photographer left behind, it proved a challenge to systematize his work. From the 19,000 negatives she found in his estate, Bakondy selected 3,500 images and digitized them. “My approach is to single out individual series in order to analyze in detail not only the content of the images, but also the history of their use,” explains Bakondy. “For, by themselves the negatives tell us nothing about how meanings change through the way the images are used, depending on the respective context and the messages that were conveyed with them.”

The project “Picturing migrants’ lives” is located at the interface of photography, visual culture studies and historical-cultural studies. It is funded by the FWF's Hertha Firnberg Program with EUR 239,000.

Visiting the “house of horrors”

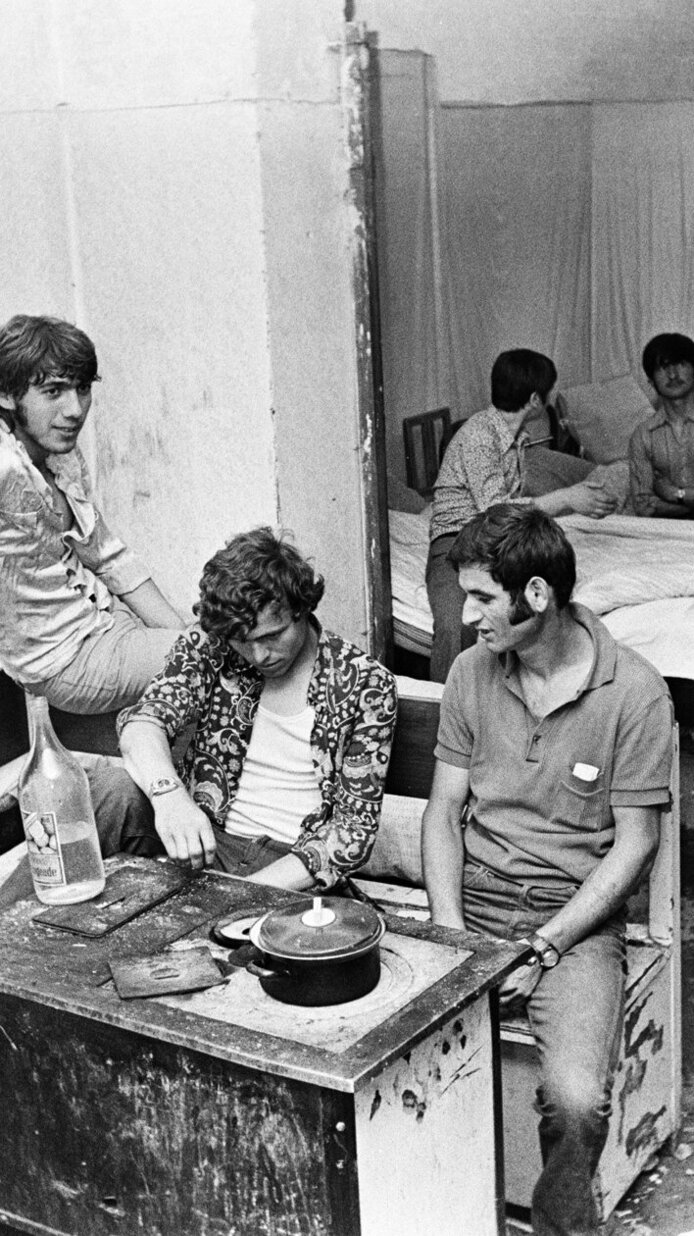

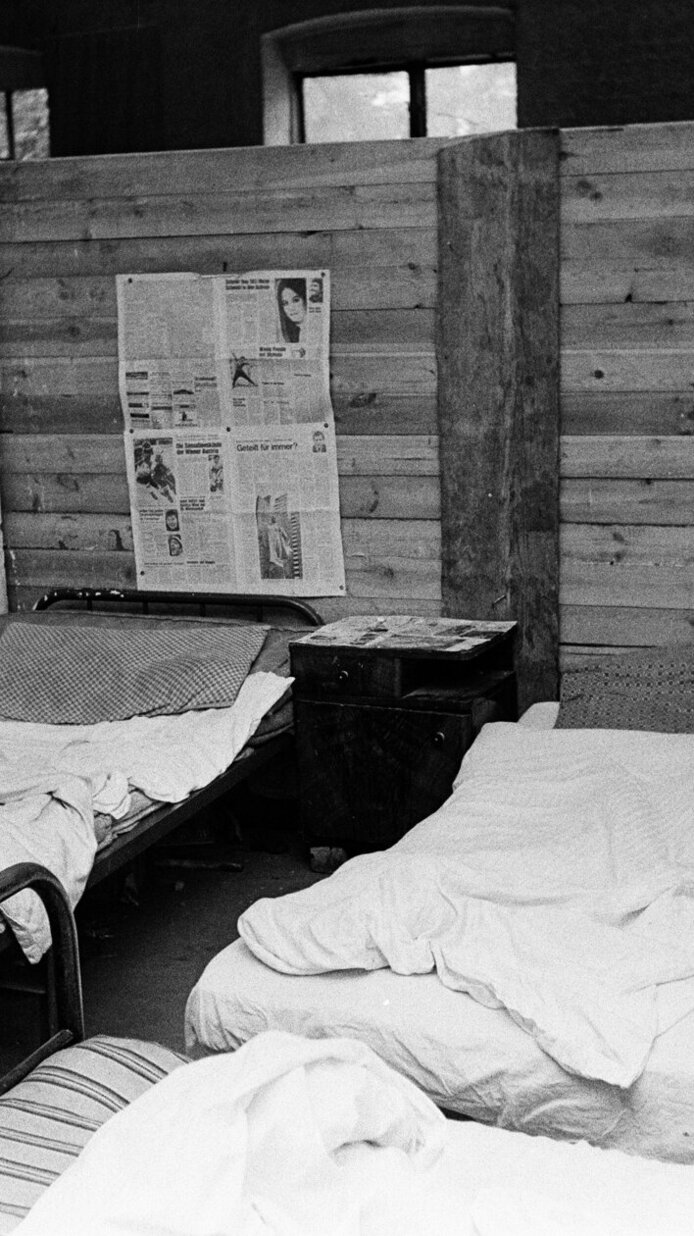

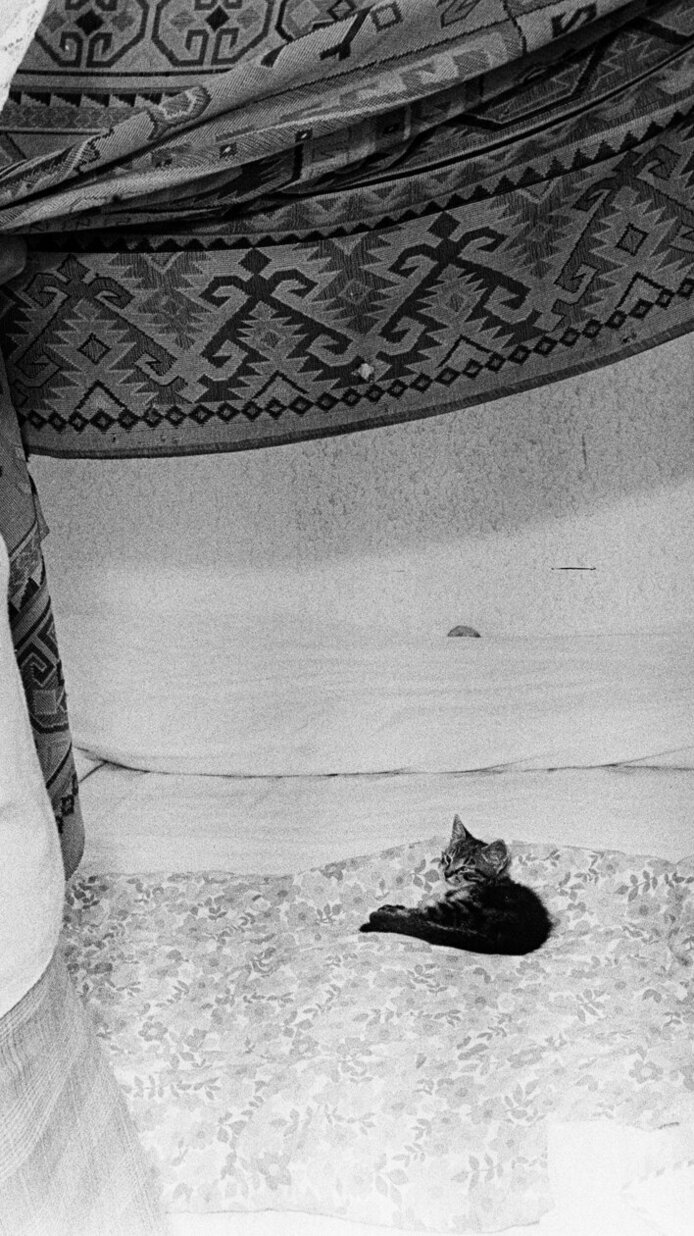

One of the series that Bakondy has selected to work on bears the title “Rio Grande - House of Horrors”. The 30 pictures dating from the early 1970s show the living conditions in workers’ living quarters on the outskirts of Vienna. “The name of the series not only refers to the decrepit state of the accommodation, but also reveals contemporary references to popular culture such as comics and films called 'Rio Grande',” explains the researcher. “Moreover, naming it after the border river between the USA and Mexico – and thus between rich and poor, north and south – also reveals a socio-critical undertone.”

The pictures show wooden sheds that divide a living space into narrow compartments. People are crowded around tables or small ovens. One particularly touching picture shows a woman opening the curtain to her sleeping area, revealing a kitten lying on her bed. “The people in the pictures show intimate parts of their lives,” says Bakondy. “Ritopečki's camera view of them is not distanced or voyeuristic, but respectful and gentle. Many of those portrayed turn their laughing faces to the camera. It is obvious that there was interaction between them and the photographer before the picture was taken.” In many cases it becomes apparent that the people portrayed and the photographer agreed on a suitable mise-en-scène.

Socio-critical tendency

Bakondy's research revealed that the pictures from the “House of Horrors” series were published in the Yugoslavian magazine “Yu Novosti”, whose target audience were Yugoslavian migrant workers throughout Western Europe. The accompanying text reveals that over 100 people were living in the accommodation under exploitative conditions. The photos were taken by Ritopečki without permission, and that the owner chased him out uttering death threats. “The title, the pictorial language and the information he researched testify to Ritopečki’s wish to document and condemn the squalid living conditions of Yugoslav migrants,” notes Bakondy. The many photos documenting the migrants' workplaces, on the other hand, paint a completely different picture. Bakondy: “Ritopečki's pictures for the newspaper 'Naš list', which was published by the Federation of Austrian Industry for Yugoslav migrants, present a picture-perfect world of work in the manufacturing enterprises.”

In her analysis of Ritopečki's work, Bakondy points out how conspicuous the presence of women is. “At the time, there were also many women migrants who lived and worked in Austria. Ritopečki's pictures show migrant women at various places of work or in their private spheres. This distinguishes his work from the majority of Austrian press photos of the time,” Bakondy explains. For Austrian media at that time, migrant women were apparently not really a topic worth covering.

Virtual exhibition

The majority of the digitized images that the historian is working on will be processed for an online database and made publicly accessible in the Visual Archive Southeastern Europe (VASE) by 2025. For this purpose, Bakondy is collaborating with the Center for Information Modelling at the University of Graz, and she also intends to have a real-life exhibition of the image series. She emphasizes that expanding the comparison between Ritopečki's view of migration and that of contemporary Austrian press photography would also make a lot of sense.

Putting the photographer’s work in this kind of context could open up new meanings and narratives: “For instance, I recall Ritopečki's photos of a residential building in Vienna's second district, which are dignified representations of its residents and their community,” says Bakondy. “I also found the same apartment building in the pictures of an Austrian press photographer, but on this occasion it was shown as the scene of a nocturnal police raid.”

Personal details

The historian Vida Bakondy is a research associate in the Balkan Studies Research Unit at the Austrian Academy of Sciences (ÖAW). In her multi-award-winning dissertation “Montagen der Vergangenheit. Flucht, Exil und Holocaust in den Fotoalben der Wiener Hakoah-Schwimmerin Fritzi Löwy” (Wallstein-Verlag 2017), she focused on visual culture studies, photography and the historical and cultural analysis of private estates.

Publications

Bakondy, Vida et al.: Fotoalben als Quellen der Zeitgeschichte, in: zeitgeschichte, 49/2, V&R unipress 2022

Bakondy V., Tropper E.: Fotoalben beforschen. Voraussetzungen, Impulse, Methoden eines interdisziplinären Forschungsfeldes, in: zeitgeschichte, 49/2, 2022

Forthcoming: An Album for Tito. Belonging, Transnational Unity, and Social Critique in a Photo Album by the Yugoslav worker’s club Jedinstvo Vienna, in: Ethnologia Balkanica. Special Issue of Contemporary Southeastern Europe (CSE), edited by Elife Krasniqi and Robert Pichler, Vol. 24/2024