“In history, violence is the rule”

On 5 May 1945, shortly before the end of WWII in Europe, the US Army liberated the Mauthausen concentration camp. This was the main Nazi concentration camp on Austrian territory and was among the last to be liberated. As the Red Army advanced from the east, the Nazis closed smaller camps and sent the inmates on so-called “evacuation marches” towards Mauthausen, Gusen or Ebensee. Many prisoners died on these death marches.

Obliterating the traces

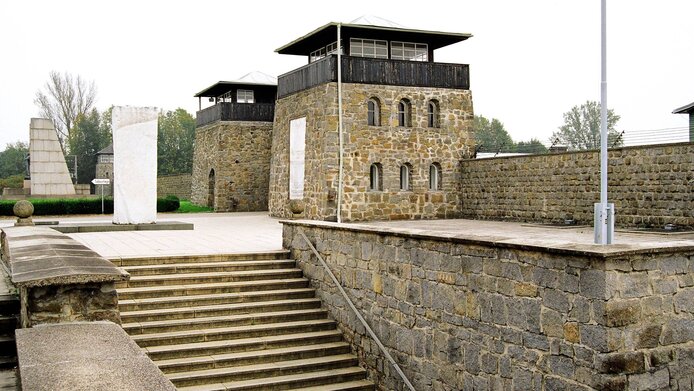

At the camp in Mauthausen, the staff also started to cover their tracks by destroying documents and liquidating “individuals with access to secret information”, the bulk of them prisoners that had been working in the crematoria. Built by the SS and its commercial subsidiaries in 1938, the Mauthausen concentration camp was not only created to punish individuals by imprisoning, torturing and killing them, but also to force them to work in the nearby granite quarries and, during the second half of the war, in the weapons industry. “Prior to the liberation in 1945, almost 200,000 people were detained at Mauthausen, at the branch camp of Gusen and the various sub-camps, where at least 90,000 of them died: they died of exhaustion, starvation, the cold, were hunted or beaten to death, sent to the gas chamber or executed”, reports Bertrand Perz.

Memorial

This history professor from the University of Vienna is familiar with the history of Mauthausen like no other expert. He started his research on concentration camps in the late 1970s, thus establishing a new field of research in Austria together with his colleagues. From 2009 to 2013, Bertrand Perz was the scientific head overseeing the redesign of the Mauthausen Memorial, an important educational institution since the 1980s. Every year 200,000 visitors come to see it, one third of them school classes. The original exhibition, opened in 1970, was one that had been designed by survivors. At the time, it was the only permanent exhibition on the topic of National Socialism. “A historical exhibition normally has a half-life of no more than 10 years, but this one lasted from 1970 until 2012”, emphasises Perz.

Redesign

Back in the 1990s, Perz co-authored a critical study on the Mauthausen Memorial and its exhibition which he considered as playing too much to the “victim hypotheses”: “Austria was presented as the first victim of Nazism, and resistance activities were given centre stage”, he observes. It was only in the year 2000, under the coalition government between the ÖVP (Austrian People’s Party) and the FPÖ (Austrian Freedom Party), that the then Minister of the Interior, Ernst Strasser, took up the issue. “There was a political motivation, of course: in the face of criticism and sanctions against Austria, he wanted to present himself as an enlightened antifascist, but at any rate things started moving with respect to the Memorial”, analyses Perz. It was to take nine years, until 2009, for the redesign to be tackled. The underlying idea was to design the historical part as a scientific exhibition and separate it methodologically from the aspect of commemoration.

An exhibition with three perspectives

Inaugurated in 2013, the main exhibition tells the history of Mauthausen from three perspectives. The general context is provided by the history of National Socialism and the war. The second narrative thread presents the history of the camp as part of a major institutional complex with satellite centres - this is the “perpetrator perspective”. The third perspective is devoted to the victims: who were the prisoners and what were their living

conditions? A further exhibition focusing on Mauthausen as a “crime scene” is located before the entrance to the gas chamber, the crematoria and the execution room, which represents a central focus of remembrance. “Very often people came and asked ‘where is the gas chamber, I’ve just got one hour’”, reports Perz, adding “but the sense of horror is not meant to be the take-home message. The preceding exhibition offers the opportunity to seriously explore the history of extermination in Mauthausen before one enters the area of reverence and remembrance. It also makes the point that there were many places in the camp were people were killed or died, not only in the gas chamber.”

The Nazi period as a point of reference

Bertrand Perz is aware of the fact that many young people today see the Nazi period as a very distant past. The question is how one can still use it as a point of reference for current events. “The Nazi era is not simply frozen history, it continues to have an impact. Some issues are now coming to the fore that people would never have imagined could flare up again once the war was over”, Perz states in alluding to current political trends. “Granted, the

problems are very complicated, but given the radical language that has become acceptable by now, I get a feeling that the current generation in Europe has simply lost all track of what happened during the Nazi period”, Perz says wistfully and adds, “it’s not a problem, however, that memorials will be able to solve”. He is convinced that memorial sites also need to reflect on current social developments in order to remain attractive. Perz considers the fact that the camp's last survivors are now dying out to represent a great caesura, a transition from communicative to cultural memory. “Input from living witnesses is generally important for contemporary history, but in this case it’s also about testimonials”, Perz believes, which is why the exhibition includes video material.

Research about the concentration camp staff

No other concentration camp had as large a staff as Mauthausen. When camps near the combat front were evacuated, not only prisoners were herded there from the east on the death marches, but the relocation also brought more SS staff to Mauthausen. In a project funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF, Perz investigated the composition of this staff which numbered almost 10,000 people. The results were surprising. Apart from the Kommandanturstab, the camp administration responsible for internal operations and managing the camp complex, there were very heterogeneous guard units. Initially composed of Germans, Austrians and Sudeten Germans, they grew to include members of German-speaking minorities from eastern and south-eastern Europe recruited as of the middle of the war. In 1944, the camp also started to absorb older members of the German army and, finally, members of the Volkssturm (a military auxiliary unit) and of the Vienna fire brigade. In contrast to the image propagated by the SS itself as being a powerful elite unit, the investigations of Perz revealed that the guard units were mainly composed of individuals considered unfit for combat – “very much the B team” as he pointedly observes.

Ideologically trained camp management

A second surprising insight was that the concentration camp worked smoothly despite the enormous turnover in the guard units. The camp management consisted mainly of long-serving SS members, individuals who had undergone ideological training and who were often extremely violent. The nationalities included Germans, Austrians and Sudeten Germans. “Those were no ‘ordinary men’, but perpetrators who acted out of ideological conviction”, notes Perz. Compared to them the guard units were a “disparate pack of ordinary people” says Perz and gives an example: “A 19-year-old farm boy is recruited in Hungary, lured by all sorts of promises. He decides: I’m going to join the SS. He is taken to Vienna, on from there to some military training area near Kraków, receives two months of training there and finally ends up in Auschwitz or Mauthausen. The trajectory from “I’m going to join the SS” to actually working as a guard in a concentration camp may well have taken just two or three months. The system was built in such a way that it was entirely sufficient for the inner circle of the camp management to be firm believers in the ideology”, explains the historian.

Violent individuals from all strata of society

A question that repeatedly came up during Perz’s studies of concentration camps is how to reconcile the portrayal of the institution with the tremendous level of violence that occurred there. The camp staff had a wide range of relationships with the surrounding region. Members of the SS

had their children in local schools, weddings were celebrated at the camp’s registry office, some camp staff played in a local soccer team. How can one explain the co-existence of these extreme poles of normalcy and violence? In order to do that, Perz and his team modified their approach. His working hypothesis was that the staff simply considered the camp as their workplace. “After breakfast, the SS commandant would take his briefcase and go to the concentration camp, do some office work, oversee an execution after lunch and go back home in the evening”, says Perz. These SS men came from the mainstream of society. There are many sociological and psychological hypotheses that attempt to explain how something like that is possible. Some tried to explain it by a common socialisation pattern, such as a very authoritarian upbringing. “Socialisation does have an effect, of course, but these popular explanations did not stand the test of time. Today, research assumes that the situation itself, the fact that a state not only condones violence but even commands its use at the concentration camp, plays an important role. Like the 19-year-old farm boy who suddenly finds himself the master over life and death. The hypothesis is that all people can be turned into perpetrators if placed in a certain context, there are enough experiments supporting this tenet. Without this interplay of personal disposition and the situation, one could not explain Mauthausen and its 90,000 deaths in an outwardly placid rural area like Austria's Mühlviertel”, notes Perz, adding: “In the past I would have believed that violence is the exception to the rule in history, but today I say: the absence of violence is the exception.”

Active thought

In his research, the 58-year-old scientist is spurred on by what Bertold Brecht called “active thought”: he wants his research to have social relevance. This is why Perz oversaw the redesign of the Mauthausen Memorial, was a member of the Austrian Historians’ Commission and serves as expert witness in lawsuits. Is it possible to learn from history? The historian professes great scepticism. “But every form of knowledge holds a lesson for the present. It is important to take a stand on certain issues”, he says with conviction.

On concentration camp research

Growing up in Linz, Perz started to take an early interest in social issues. He witnessed heated political debate at home. Although he started out studying geology in order to do something ‘solid’ – as he calls it – he soon realised that this was not for him and took up history, a study course he engaged in with somewhat “leisurely dedication” because he enjoyed the “luxury of receiving financial support” from home. In the late 1970s, the then

Minister of Science, Hertha Firnberg, commissioned the historian Erika Weinzierl to do research on the sub-camps around Mauthausen. Attending a seminar on concentration camps at the time, Bertrand Perz was asked whether he was interested in the project. This was his introduction to a new field of research. “At that time you quickly became an expert for a given topic, because in a small country it was rare that someone else would be working on the same specific issue”, he recalls and regrets that “in the face of strong internationalisation and the competition for funding in the sciences, young people rarely have the opportunity to stay in a field of research for long and develop it without being forced to cater to the market”. Many of his project team members have a side job or opted to qualify as teachers after their PhD in order to have a second means of support.

Is research a luxury?

For the university professor this holds true in more ways than one: research necessarily takes second place to his administrative obligations and teaching activities at Austria’s largest university. He can only give it marginal attention during worktime and pursues it in his leisure hours. On the other hand, he sees a problem for people seeking to enter and/or exit the world of research. “There’s practically no easy access road to research. With the expiry of the Future Fund[¹] we are losing a source of funding”, Perz regrets. He would like to see funding vistas that enable young scientists to take up small projects involving smaller amounts of money. “Submitting an application to the FWF is time-consuming and the approval rate is low. You need to be very experienced to do that”, he argues. On the flip side, he considers it a challenge to retain people who are really good. “You can go on employing people on the basis of third-party funding. But they get older, and then what?”, he warns and recalls an excellent colleague who trained to become a kindergarten teacher after his grant from the Austrian Academy of Sciences expired just to be able to ensure his livelihood. “When highly qualified people in whom a lot of public money has been invested are unable to continue on their trajectory, something is wrong with the system”, Perz asserts. This is why he would like to see opportunities other than professorial posts to enable scientists to work in science with a secure financial basis.

Since 2006, Bertrand Perz has served as Deputy Head of the Institute of Contemporary History at the University of Vienna several times. He was the scientist in charge of the redesign of the Mauthausen Memorial and a member of the “Commission of Historians of the Republic of Austria”. In addition to various other functions, he is a board member of the association “Vienna Wiesenthal Institute for Holocaust Studies” (VWI), a board member of the “Documentation Centre of Austrian Resistance (DÖW)” and president of the “Austrian Society of Contemporary History”. His main research interests are National Socialism and the Holocaust, wartime economy and forced labour, Nazi occupation policies, remembrance policies and memorial sites.