How microbes could help us lose weight

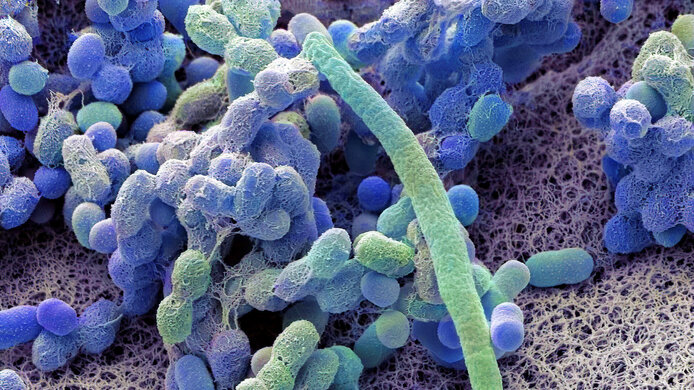

Human beings are more than meets the eye. There are about as many microorganisms living on and inside us as we have body cells. They form the human microbiome and constitute roughly from one to three percent of our body weight. The microbes in our gut have a particularly important role to play. They not only help us digest food and absorb nutrients, they also have a significant impact on our health and psychological well-being.

Together with colleagues from Germany, Julia Mader from the Medical University of Graz is conducting a pilot study to learn how the gut microbiome affects obesity. In the FWF-funded project “Characterizing Fecal Microbiota Treatment in Human Obesity,” the researchers are transferring gut microbes from people who are not overweight and from those who have undergone gastric bypass surgery to people who are overweight.

It has already been shown in animal experiments that this can lead to weight loss. In the future, a successful transplantation of the gut microbiome could serve as a less invasive therapeutic measure for weight loss.

Microbes: the key to understanding diseases

Scientists believe that the microbiome influences diseases such as allergies, asthma, diabetes mellitus, and obesity, as well as depression and autism. Researchers around the world are therefore trying to decipher the functions of the microbiome.

More complex than just eating less and exercise

“In the long term, severe excessive weight – in other words, obesity – can increase the risk of developing various diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease and even cancer. This is a global problem,” explains Mader. “Moreover, those affected often suffer from social stigma. The problem is that the simple formula of losing weight by getting more exercise and eating less doesn't work as easily as one might think.”

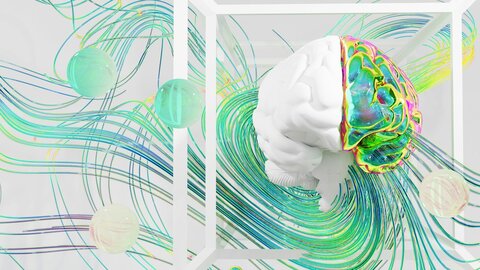

Excess weight is a complex phenomenon with a whole network of causes. It is a multi-layered interaction between metabolism and various hormones, the microbiome, and even the nervous system and brain that regulates how much energy the body can and wants to absorb through food. Much of this happens subconsciously, as hunger and the sense of fullness cannot be consciously controlled.

“The brain is determined to hang on to a so-called 'maximum weight' – which the body interprets as the ideal weight based on prehistoric times when food was scarce and malnutrition was common. This is largely genetically determined,” explains Mader. The brain accordingly believes subconsciously that this 'ideal weight' gives it an evolutionary advantage. In times of excessive caloric intake like we live in today, this can result in obesity.

The power of microbes

Thus the brain works together with other body systems in order to prevent weight loss. This makes it so difficult to lose weight and then keep it off. “If we could change the gut microbiome so that it doesn't collaborate with the brain’s efforts to prevent weight loss, that would be a huge help,” says Mader.

“Experiments with animals have shown that the microbiome of overweight animals differs from that of animals with no excess weight,” Mader notes. The composition of the various types of bacteria in the gut is influenced by the type of food we eat, and the chemical signals emitted by the bacteria can in turn have an impact on eating behavior and the feeling of hunger.

It is exciting to learn that one can transfer to an overweight mouse the gut microbiome of a mouse that is not overweight. The former then changes its eating habits and also loses weight. “We are now investigating this in humans in a pilot study,” says Mader, explaining the goal of her research.

Starting small

In the ongoing study, the researchers are investigating a total of 30 severely overweight individuals in three groups. The ten people in each group will receive the gut microbiomes of different donors. Before the recipients receive the donations, however, their own gut microbiome must be removed as completely as possible through antibiotic treatment so that the donated microbiome can colonize their gut.

The first group will receive the microbiome of overweight individuals who have undergone successful gastric bypass surgery and lost weight as a result. The second group will receive donations from individuals who are not overweight. The third group will serve as a control group and will receive samples from their own gut microbiome. While this does not change much for the control group, it is important to have it in order to get values to compare to the other two groups.

“It wasn't easy to find test subjects, as we had very specific criteria for them so as to ensure that the study would have a meaningful outcome,” says Mader. “We searched for a long time and through various channels, including databases, notices posted in doctors' offices, and online.”

Although a sample of 30 people doesn't sound like a lot, Mader is confident: “This is a first pilot study. We don’t need it to deliver perfect results, we just want indicators of whether the desired effect actually occurs.”

For this study, Julia Mader is collaborating closely with Patrizia Constantini-Kump from the Medical University of Graz and Wiebke Fenske from the University of Bonn. “We conducted the microbe transplants in Austria because that process is much more rigorously regulated in Germany. Our German colleagues are making a significant contribution to the examinations before and after the transplants,” says Mader.

No longer craving fast food

After the microbiome transplant, the recipients are monitored for over six months. They undergo blood and metabolic tests, their microbiome is examined, and they fill out questionnaires about their eating habits.

“One person reported that after the transplant, their craving for fast food had completely disappeared and they now find it repulsive,” Mader says with a smile. “That sounds very promising, but it's just a single data point, which doesn't mean much on its own. We also don't know yet which group the person was in or whether they received a new microbiome at all.” Mader and her colleagues are unaware of this as yet, since this was a double-blind study, which means that neither the researchers nor the participants knew who had been assigned to which group.

“We are currently in the process of finalizing the evaluation of the data,” says Mader. “The animal experiments were very promising, and we hope that it will work in humans as well.” Although intestinal microbiome transplants are already being used as a therapeutic tool, it will probably be some time before one can combat obesity simply by ingesting capsules that contain microbes.

About the researcher

Julia Mader is a professor of medicine at the Department of Endocrinology and Diabetology at the Medical University of Graz and deputy head of the diabetes outpatient clinic. Between 2016 to 2017, she was a visiting professor at the University Hospital of Bern in Switzerland. At MedUni Graz, Mader heads the Diabetes Technology Research Unit. Set to run until June 2026, the project “Characterizing Fecal Microbiota Treatment in Human Obesity,” has been awarded EUR 264,000 in funding from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF).