“Greetings” from Lower Styria

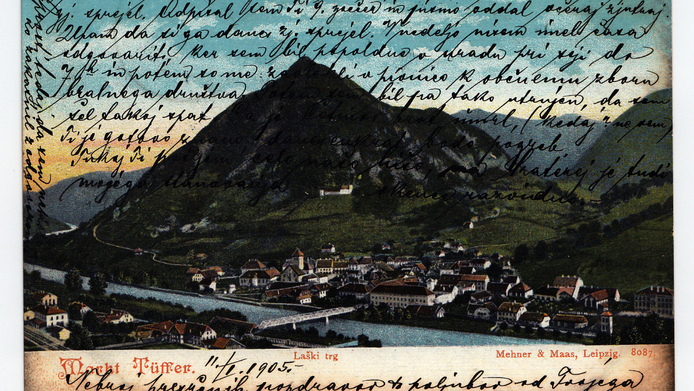

Historical postcards are not only a collector's item: sometimes they also prompt questions. Why, for instance, was Cilli, the German name for the Slovenian city of Celje, crossed out by hand on a postcard from 1914? And what is the significance of the arrow pointing towards the factory on the postcard, accompanied by the Slovenian words “Tukaj nekje pa poteka moje življenje!” (“My life moves along here somewhere!”)? For the inveterate postcard collector and Slavist Heinrich Pfandl from Graz University’s Institute of Slavic Studies, postcards like these are of particular scientific interest. For he and his team are intent on demonstrating the connections between nation, language and identity on the basis of postcards from the historical region of Lower Styria (Spodnja Štajerska) from the period between 1885 and 1920.

From private to online collection

The starting point for this FWF-funded project was the researcher's own private collection of postcards: Pfandl possesses about 500 postcards from the time when the two Styrias - one in Austria and one in today's Slovenia - still belonged together. Within the framework of the research project, which ends in 2019, the team has viewed and analysed around 10,000 postcards from collections in Austria and Slovenia and processed example cases. Interdisciplinarity plays a central role in this undertaking. The photo historian Eva Tropper, for example, contributes her expertise to the virtual presentation of image sources. The historian Karin Almasy is an expert on this particular region. In order to provide online access to the postcards and to the knowledge gained from them, the most meaningful items, i.e. around 2,000 cards, will form the basis for a virtual postcard collection for Lower Styria (POLOS) which is currently being set up. This database was created in cooperation with the Center for Information Modelling of the University of Graz (ZIM/ACDH) and will be integrated into the "Visual Archive of Southeastern Europe" portal in 2019. The results of the project can also be seen in the exhibition “Štajer-mark” in the Pavelhaus near Bad Radkersburg until 2 March 2019.

Postcards depict bilingualism

There is one thing that is important to know so as to understand the historical situation: At that time postcards were still a fledgling means of communication. Very often – and unlike today – they were used for everyday communication in private and business life, since they could be delivered on the same day. The first official postcards were called “correspondence cards”, “dopisnice” in Slovenian. In Lower Styria they were also available with pre-printed text in both languages as from 1871. Moreover, postcards were cheaper to send than writing letters. All this made them attractive as a means of written communication for large parts of the population: While written correspondence had previously been more a prerogative for the German-speaking urban population in the region, the postcard now also made it possible for the Slovenian-speaking population, who lived predominantly in rural areas. Numerous examples show that people often use both languages in the same text. “One postcard begins in German saying ‘Welche Überraschung!’ ('What a surprise!'), followed by several lines in Slovenian. We assume that the author did not know how best to convey surprise in Slovenian”, explains project manager Heinrich Pfandl. Surprise was a so-called “cultural notion”, and there were several such terms and also military expressions or concepts of modernity, such as trains, for which there were no widely used, uniform designations in Slovenian at that time. In these cases correspondents tended to switch to German which was clearer and also more prestigious. According to Pfandl this was comparable to our use today of English terms in German.

From coexistence to conflict

Due to the dominance of the German language, Slovenian was mainly used as a spoken language for a long time and hardly ever written down, which meant it was less common in written correspondence. Although the language was present in the everyday life of the Slovenian-speaking population, it had little public visibility. With the advent of bilingual postcards this situation improved somewhat. The bilingual texts were motivated primarily by economic interests related to links with the Southern railway line and the growing importance of tourism. “When German-speaking Austrians and Slovenes saw their respective languages featuring on the postcard, this boosted turnover”, explains Pfandl in the interview with scilog. Nevertheless, there was an imbalance because bilingual formats were not available everywhere and from all locations in Lower Styria. The Slovenes thus had less choice and less opportunity for identification. This was particularly noticeable in Zidani Most, formerly Steinbrück, where the researchers found very few postcards pre-printed in Slovenian. The grudge against this underrepresentation, coupled with a growing national self-confidence, can be traced on postcards from the beginning of the 20th century onwards. “In the past, if an expression was lacking in the correspondent’s own language, they would simply insert it, but over time the gaps started to irritate people and they rigorously deleted the pre-printed designation”, Pfandl notes. The increasing polarisation between German-speaking Austrians and Slovenes is also reflected by pejorative comments made by both sides. This was further reinforced by postcard motifs such as national banners or institutions, as well as stamps with political slogans giving prominence to the one or other national side.

True to life

As the research project illustrates, postcards were much more than a neutral means of communication at the time. They show how language, nation and identity were interwoven in people's everyday lives and what influence the possibility of communicating by postcard had on the development of the budding Slovene language. One has to know all this in order to understand the underlying significance of the deletion of a city name mentioned here at the outset, and this understanding is also the basis for being able to answer further questions in the future.

Personal details Heinrich Pfandl comes from Carinthia and speaks both official Carinthian languages. He is a Slavist at the Institute of Slavic Studies at the Karl-Franzens-University in Graz and the principal investigator of the FWF project "Nation, Language and Identities on Picture Postcards", which runs until autumn 2019.

Project website: https://postcarding.uni-graz.at/

Publications