Exile equates with translation

“After three years we are starting to really grasp how vast a field we have set our sights on and how little we knew about it,” says Larisa Schippel, a researcher from the University of Vienna who has spent the past three years doing intensive research on a sinister and forgotten chapter of Nazi history. In cooperation with the universities of Lausanne and Mainz/Germersheim, Schippel and a team of researchers in Vienna initiated the Exil:Trans project, which is dedicated to the lives and work of translators who were persecuted by the Nazis and forced into exile.

The interest of the three project teams was aroused by a great deal of preliminary studies and a number of facets connected with the topic. Schippel recalls that the initial spark was provided by a “Long Night of the Sciences” event in Berlin several years ago. The date coincided with the 75th anniversary of the Nazi book burning on May 10, 1933. “In order to mark the occasion, we organized a reading from translations of notable authors whose books ended up in bonfires alongside those of German writers, including Jack London, John Dos Passos, Henri Barbusse, and many Russians. We wondered what had become of the translators.”

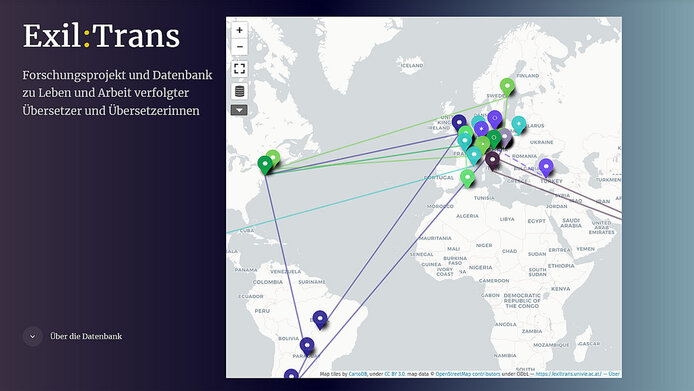

Public online database combines results

A lot has happened since then. Third-party funding has been successfully obtained in Austria, Germany and Switzerland; the respective teams have distributed their focus across different spheres and fields of activity, and the first joint research project was launched in 2019. The teams in Mainz and Lausanne focus on literary translations and archives – most of the regrettably small number of translators' estates are to be found in Switzerland – while the team in Vienna explores translations of scholarly texts. Several results have already been published and the first of three volumes is available. It features portraits of selected translators as well as the bibliographies of their translation work, which will be published successively in the Digital Library and Bibliography of Literature in Translation at the University of Vienna as well as in the Germersheim Übersetzerlexikon. In addition, the freely accessible Exil:Trans database has recently gone online. It provides information on the biographies, translation activities and routes followed into exile which often involved many waystations.

Comprehensive biographical research

All of this data was painstakingly collected by the research teams who vetted archives from Moscow to New York. Some information was also found in the blacklists kept by the Nazi regime. Sometimes the finds were aided by happenstance, by a chance contact or name that enabled the team to locate surviving relatives, as in the case of Harry Zohn. A literary historian, Zohn fled from Vienna to Boston via London in 1938 and translated texts by authors including Karl Kraus, Walter Benjamin and Martin Buber into English. “The challenge,” notes Schippel, “resides in the fact that translation and everything related to it is not an archival subject. Hence we have to use other ways to work our way through the archives.” This situation is slowly changing however. In the meantime, the literary archive in Marbach has also been devoting attention to translators and their estates.

Language skills as a survival trait

In general, there is still a lack of awareness of the importance of translators, even though a lot of things have changed for the better. Many who work in this professional field live precariously and have to boost their income through various different activities. Although it was produced under extreme conditions, the work of translators in exile also illustrates the general aspects of translation, which depends on political, economic and social conditions and has an impact on the most diverse fields. In exile, translators were particularly in demand, be it in broadcasting, in science, in the secret service or when it came to working with authorities. Some only began work as translators in exile, thus reaping the fruit of their language skills. Others, on the other hand, began their translation work after their exile. The journey into exile itself requires all kinds of translation activities, beginning with the translation of the documents needed upon arrival in the country of exile or during the various stages of exile, such as the internment camps, where many emigrants landed at the outbreak of WWII. “Exile really equates with translation, acting as a translator or being translated, acting as an interpreter and being interpreted,” notes Schippel.

Exile Publishers in Switzerland and the Soviet Union

According to Schippel, literary translators (who worked into German) found it particularly challenging to gain a toehold in the country of exile. “For them it required switching languages and good local networking.” There were only limited possibilities to do this through exile publishers. Literary translators had it easier in countries where there were significant German-speaking minorities that had their own publishing system and structure, such as in the Soviet Union. There, literary translation into German existed on a notable scale. Refugees were also able to become established in Switzerland and at the exile publishing houses there. Lucy von Jacobi was a case in point: she worked in Switzerland as a translator into German, first from French and later also from English, despite her precarious lack of a work permit or residence permit.

Closing research gaps

Interdisciplinary exile research as well as individual works about the history of science have already provided good groundwork. The Exil:Trans project has now made a significant contribution to having translators included in this research and no longer getting only a chance mention. Since the topic is far from exhausted, the teams have already planned a follow-up project to trace the work of translators beyond the period of the Nazi dictatorship and to raise public awareness of the importance of translation.

Personal details

Larisa Schippel is a translation scholar, linguist and translator. She completed translation studies for Russian and Romanian in Germany and conducted research at Humboldt University. Meanwhile a professor emeritus, Schippel held a chair of transcultural communication at the Center for Translation Studies at the University of Vienna starting in 2010. The D-A-CH research project “Exil:Trans - Life and work of translators in exile” (2019–2023) received EUR 387,000 in co-funding from the Austrian Science Fund FWF.

Publications

Tashinskiy A., Boguna J., Rozmysłowicz T. (ed.): Translation und Exil (1933–1945): Namen und Orte. Recherchen zur Geschichte des Übersetzens, Bd. I, Frank & Timme 2022

Dietiker P., Rougemont M., Weber-Henking I. (ed.): Translation und Exil (1933–1945) II. Netzwerke des Exils. (in print, Frank & Timme)

Kremmel St., Richter J., Schippel L., unter Mitarbeit von Tomasz Rozmysłowicz (ed.): Österreichische Übersetzerinnen und Übersetzer im Exil. Vienna: nap 2020