Deportations in Poland under dual occupation

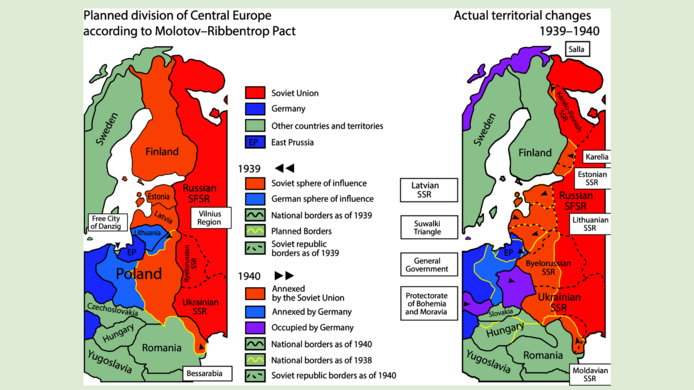

In September 1939, within a period of just over two weeks, Poland was invaded by two despotic regimes. In a secret protocol added to the “Hitler-Stalin Pact”, Germany and the Soviet Union had already divided up their spheres of influence in Eastern Central Europe, including Poland.

In the Wehrmacht's wake came German security police forces, and the Red Army was followed by operational groups of the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD) – organizations that originated from systems that, while completely different, were of similar radicalism. Both the police forces and the operational groups carried out mass arrests, mass deportations, and mass murders.

In June 1941, Germany ultimately attacked the Soviet Union and advanced further east. But during roughly 21 months, Poland was occupied by the two opposing regimes. Historians Hannah Riedler and Alexandra Pulvermacher from the Department of History at the University of Klagenfurt considered this constellation to be an opportunity for contemporary historical research. In the FWF-funded project “Violence in German and Soviet occupied Poland, 1939-1941” they conducted comparative research on the two dictatorships. “The division of Poland into two areas of approximately equal size provided us with almost ideal conditions for a synchronous comparison of the two occupations,” notes Pulvermacher.

The researchers’ focus was on the forced resettlements undertaken by the two occupying powers, which fundamentally changed Polish society. “The German occupying powers deported 400,000 Polish citizens in a period of only 21 months, while the Soviets deported 330,000,” outlines Pulvermacher. “The German occupiers resettled Poles and Jews within the occupied territory, whereas the Soviets deported Poles, Jews, Ukrainians, and Belarusians from eastern Poland to the interior of the Soviet Union.”

Poland under double occupation

On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland, followed by the Red Army on September 17. From that point on, Poland was subject to the rule of two radical and completely opposing occupying powers for 21 months – a unique case in Europe. An FWF project has investigated how the German and Soviet occupying forces each removed and deported around 400,000 Poles within a short period of time.

Chaos after double invasion

The two invasions plunged Poland into complete chaos. The German Wehrmacht and Luftwaffe in particular acted with extreme brutality. “Germany used the attack to test new weapon systems and subjected cities, but also columns of refugees, to mass bombardment. Thirty percent of Warsaw was destroyed,” says Pulvermacher. “When the Red Army then attacked from the east, everything spiraled completely out of control. Initially, the Red Army soldiers did not present themselves as invaders, but as defenders against the Germans. But at the same time, they imprisoned hundreds of thousands of Polish soldiers.”

In the end, it took only a few weeks for the Polish army to surrender. While the Soviet Union annexed the entire eastern part of Poland, Germany only incorporated northern and western Poland. Central and southern Poland was declared the Generalgouvernement (General Government). It served as a source of economic exploitation, a destination for undesirable segments of the population, and an area for the Wehrmacht to assemble for the planned campaign against the Soviet Union.

The deportation machineries on both sides are relatively well documented: for the West by the records of the Umwandererzentralstelle (UWZ), the German authority that coordinated the displacements; in the East by documents of the NKVD, whose many sub-organizations not only acted as police, secret service, judges and henchmen, but were also responsible for the mass deportations. In the research project, this data was compiled and analyzed together with reports from eyewitnesses, victims and other sources.

Deportations to the General Government and the interior of the Soviet Union

“Both occupying powers carried out the deportations with great brutality. However, they differed both in their motivation and in the strategies they employed,” explains Pulvermacher. The German occupiers sought to “Germanize” the territories they incorporated into the Reich. All Jews and large parts of the ethnic Polish population were to be resettled into the General Government. “These early deportations were far less deadly than the transports that sent the Jewish population to the extermination camps, where up to 50 percent of those deported died during the journey. The early forced resettlements were aimed at removing undesirable sections of the population, but not at systematically murdering them,” notes Pulvermacher.

“In overall terms, the Soviet regime was more inclusive – everyone living in their territory was recognized as a Soviet citizen. At the same time, the newly annexed territories were preventively 'cleansed' of social groups that were considered 'unreliable elements',” explains Pulvermacher. More than 90,000 Jews were deported to the interior of the Soviet Union. They and hundreds of thousands of Polish citizens were taken to special settlements or, if suspected of “anti-Soviet agitation”, to one of the many gulag camps. For those deported, this meant hunger, cold, and often death.

Comparatively well-organized Soviet authorities

“The NKVD's efficiency lay in its rapid and concerted implementation. It enjoyed enormous staff reserves, and its measures were more focused, faster, and more elaborate than those of the Gestapo and other Nazi organizations. In particular this was true of the Soviet surveillance apparatus. On the Stalinist side it was operational on a broad basis within a very short time thanks to involvement of the population in an informer network,” explains Pulvermacher. “Humanitarian aspects were not deemed a priority on either side.”

At that time, Germany had little experience with mass deportations. “Incompetence, staff shortages, organizational chaos, and completely unrealistic planning wreaked havoc, especially in the first months of the occupation, and resulted in a great many casualties. The NKVD, on the other hand, benefitted from decades of experience in organizing large-scale resettlement campaigns,” says Pulvermacher. Her take on the situation contradicts widespread perceptions about the German and Soviet deportation machineries.

While the Stalinist occupiers implemented standard methods, the German side changed their measures constantly. It is true that the early German resettlements and the associated ghettoization were not initially aimed at murdering the Jewish population, but Pulvermacher believes that they cannot be viewed as entirely unrelated to the Holocaust. “These deportations can certainly be considered an important step on the road to Auschwitz,” she notes, “because they gave the Germans a great deal of experience with the process. As their radicalization increased, it ultimately led to the systematic deportation and murder of European Jews.”

About the researchers

Alexandra Pulvermacher studied history and Slavic studies at the University of Klagenfurt, where she received her doctorate in 2023 and where she has held a position at the Department of History since 2024. Hannah Riedler studied Eastern European history in Vienna and received her doctorate in 2024 from the University of Klagenfurt. She is currently a postdoctoral researcher at the Austrian Academy of Sciences. The project “Violence in German and Soviet occupied Poland, 1939–1941,” which ran from 2023 to 2024 under the lead of German historian Dieter Pohl, received EUR 183,000 in funding from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF).

Publications

Riedler, Hannah: Fahrt ins Ungewisse: Die deutschen und sowjetischen Deportationen im doppelt besetzten Polen 1939–1941 im Vergleich, erscheint 2025/26 im Böhlau Verlag

Pulvermacher, Alexandra: Poland under German and Soviet Occupation 1939–1941: Approaches to a Comparison, in: Zeitschrift für Ostmitteleuropa-Forschung 2023

Pulvermacher, Alexandra: Early Deportations of Jews in Occupied Poland (October 1939–June 1940): The German and the Soviet Case, in: Holocaust and Genocide Studies 2022