Danubian narratives

At a meeting on the EU Strategy for the Danube Region (EUSDR) in Vienna in late September 2022, the President of the Vienna Provincial Parliament Ernst Woller (SPÖ) expressed his solidarity with Ukraine, emphasizing the importance of cross-border cooperation. Also present at the meeting, the Ukrainian Deputy Minister for European Integration and Chairman of the EUSDR, Igor Korkhovyi, described the Danube as the river of life for Ukraine and an important line of security. This goes to show that a metaphor popular in the 19th century, comparing the Danube to a connecting bond between peoples and nations, is still in use today.

But has the Danube really had as great an impact on the identity of its ten riparian states as has been attributed to it? How have the political upheavals of the 20th century – the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, World Wars I and II, the Iron Curtain, the end of the Eastern Bloc, the Yugoslavian War and the break-up of Yugoslavia – changed the image of this common bond? Is the Danube indeed the “great integrator,” as Hungarian author Péter Esterházy phrased it in his book Donau abwärts? These are the questions that the three-year research project “Reading the Danube. (Trans-)National Narratives in the 20th and 21st Centuries”, using literary texts, films and photographs from all of the riparian states of the Danube. Based in Vienna and Tübingen, the project is funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF and the German Research Foundation DFG.

Inspiring collaboration

The research project had its genesis in an unusual connection: the German scholars Edit Király, a native of Budapest, who teaches there and lives in Vienna, and Olivia Spiridon, who was born in Sibiu and now lives in Tübingen, joined forces and for several years organized a literary seminar on the Danube for participants from all Danube countries on a Danube Island near Budapest. As a result, they published an anthology of approximately 500 pages on this subject entitled Der Fluss (the river) in 2018.

Far from having exhausted the topic, the two researchers engaged in a follow-up project, in which other media will also be examined. They were able to recruit the photo-historian Anton Holzer and, as principal investigator, Christoph Leitgeb, who conducts research at the Institute of Culture Studies and Theater History at the Austrian Academy of Sciences in Vienna. The doctoral student Branko Ranković from Novi Sad completes the team, which cooperates with research centers in other cities along the Danube.

Danubian narratives, as diverse as the river itself

This basic research project focuses on the diversity of Danube narratives. The interdisciplinary team wants to illustrate how these narratives emerged and changed over time. The famous poem “A Dunánál” (By the Danube) by the renowned Hungarian lyricist Attila József serves as a typical example, as Edit Király tells us: “Individual elements of this poem have been incorporated into other poems, breaking up the classical topoi featuring in the original. This is important to know, because in Hungary everyone associates this poem with the Danube.” Another famous example Király quotes is the waltz “The Blue Danube” by Johann Strauss II, which he composed as a choral waltz for the Vienna Male Voice Choir in 1867. As Király notes, there is hardly another work that has undergone so many intra- and transcultural transformations.

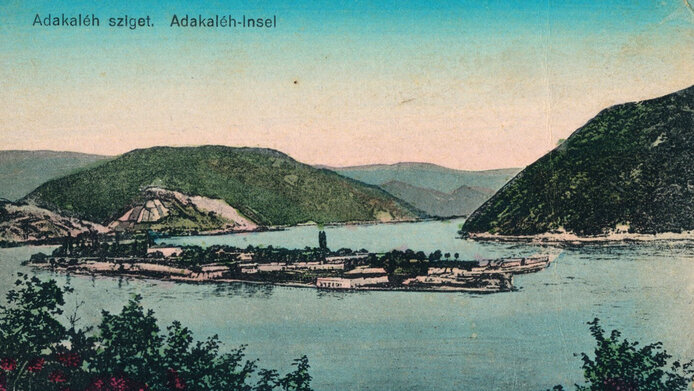

Composed as a rousing carnival entertainment for a country that was then suffering from the effects of the lost war against Prussia, the waltz became a popular evergreen. The color of the Danube, which mostly appears brown, green or muddy yellow in real life, was described as “blue” in two poems by the Hungarian-born poet Karl Isidor Beck. The color blue also symbolizes innocence, purity and longing. In the colored picture postcards, produced in large numbers from 1900 onward and easily available, the Danube was also shown as blue, and in this color it went around the world, as Anton Holzer can prove with historical examples. In literature, the blue Danube and the Blue Danube waltz were also often used as a symbol of ambiguity or dishonesty, as for example in Ödön von Horváth's play Tales from the Vienna Woods”, notes Edit Király.

Vein of life, border, nature sphere

The landscape and the people along this river are marked by many connecting and also separating elements, by many images and experiences. Accordingly, the Danube was seen as either a link between West and East or as a borderline between the Ottoman Empire and the West. Then again, the Danube was often used as a metaphor for life or the course of history, explains Christoph Leitgeb. Individual memorial sites were given an exaggerated meaning beyond their actual significance, such as Mohács in Hungary or the island Ada Kaleh, located between Romania and Serbia and with strong Ottoman ties, which was submerged during the construction of the Iron Gates hydroelectric plant.

During the Cold War, the Danube was a dangerous border. Many of the people who tried to cross the river from Romania to Yugoslavia died in the process. The view across the river as a symbol of yearning and mortal danger has featured in films and literature many times, and Olivia Spiridon has analyzed some of these films. For a long time, the technical management and economic use of the river had positive connotations in all Danube countries, says Anton Holzer. This changed when in the early 1980s the ecological movement arose against power plants and in favor of saving the floodplains. Instead of being seen as a waterway or a tool for power generation, the Danube is now also seen as a nature sphere.

The research project “Die Donau lesen” has processed a wealth of material, which has already been the basis of several technical papers and books. The project website provides an overview of the team's work with images and short texts. Deeper insights will be provided after the conclusion of the project in a book in English which will be published in late 2023.

Personal details

Anton Holzer grew up in Alto Adige and studied history, political science and philosophy. He lives in Vienna, where he works as a photo historian, author and exhibition curator.

Edit Király was born in Budapest, studied German, Sociology and Hungarian Studies at the ELTE Budapest University. She is a lecturer at ELTE and lives in Vienna as a literary scholar, translator and collaborator on projects in the field of cultural studies.

Christoph Leitgeb hails from Innsbruck, studied history, English and American studies and German studies, and is a research associate at the Institute of Culture Studies and Theatre History at the Austrian Academy of Sciences in Vienna.

Olivia Spiridon was born in Sibiu, Romania, and studied German and Romanian studies, psychology and history, in Sibiu and in Passau. She heads the literary studies / linguistics research area at the Institute for Danube-Swabian History and Regional Studies in Tübingen.

Publications

All books and essays relating to this research project are listed on https://www.diedonaulesen.com. The website is continuously updated.

To be published soon: Anton Holzer, Edit Király, Christoph Leitgeb, Olivia Spiridon: Der montierte Fluss. Stuttgart: Steiner 2023 (in press)

Published most recently:

Holzer, Anton: Sommerfrische und Verbrechen. Mauthausen-Bilder auf Ansichtskarten, in: Zeithistorische Forschungen / Studies in Contemporary History 19, Heft 1, 2022

Király, Edit: Österreichs Donau: So silbern, so blau, so schön, in: Hebenstreit D., Herberth A., Kaufmann K., Schönsee R., Tezarek L., Zolles Chr. (Hg.): Austrian Studies: Literaturen und Kulturen. Eine Einführung. Wien, Praesens, 113–122, 2020