Courageous staff for building up a bureaucracy

1718: The climate in the Banat of Temeswar, which covered present-day Western Romania, the Serbian Vojvodina and south-eastern Hungary, took some getting used to. In an area where hardly any swamps had been drained, hot summers involved the risk of getting malaria. Climate hazards notwithstanding, the conquest of the Banat of Temeswar brought many Habsburg military and civilian personnel to this region, where they became central actors in the construction of a “modern” bureaucracy. Who they were and how staff management developed in this remote, sparsely populated region has now been investigated for the first time in a research project supported by the Austrian Science Fund FWF.

Starting (almost) from scratch

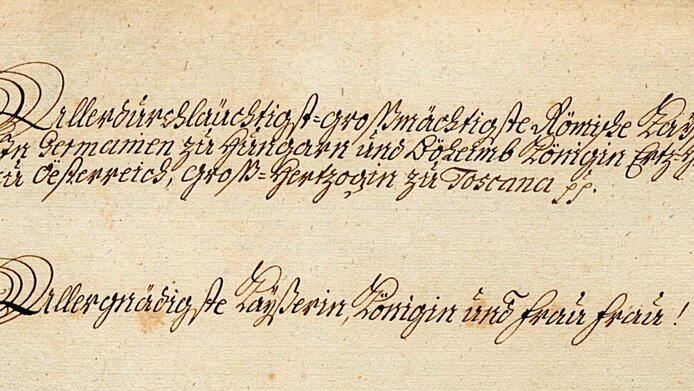

With its focus on human resources management, this basic project, which will be completed in autumn 2018, closes a research gap. “The modern aspect of the system was the professional competence of those in charge, the planning underlying the functional processes and the high quality of documentation. Today, this enables us to reconstruct such ‘management’ processes”, explains principal investigator Harald Heppner, a historian and expert for south-eastern Europe at the history department of the University of Graz. There are probably several reasons why it was this region that served as a testing ground for the establishment of a bureaucratic structure. For one, the Banat was sparsely populated due to the war between the Habsburgs and the Ottomans. Add to that its special status as a “crown domain” until 1778: this meant in practice that there was no feudal “counter-world”, which the Habsburgs would have had to take into account. The only thing they adopted from the Ottoman administrative structures was their system of village headmen.

More obligations, better services

Under Ottoman rule, the local Serbian and Romanian population was primarily expected to pay taxes and provide military services, a situation that gradually changed under the Habsburgs. “Modern administration sought to impose generally applicable rules on life wherever the public and private spheres overlapped as this was supposed to lessen the inefficiency of pre-modern administration”, says Heppner. The population felt, however, that the demands made on them were uncommon and strict compared to the Ottoman period, which is why the changes sometimes met with resistance. Whilst authorities were set up to address citizens' concerns, the latter had to respond by registering with the authorities, sticking closely to working hours, especially at the border, or by paying taxes on time.

A demanding job

Then just as today, the administrative staff was responsible for the orderly working of the system. In Banat Temeswar, which was on the outer border to the Ottoman Empire, the administration was initially manned mainly by military personnel. From the middle of the 18th century the situation changed and civilian staff became more significant. One vital result of the research project concerns the question of who these early “civil servants” were, what they brought with them and what their typical professional backgrounds were: the majority were well educated and came from other provinces of the Habsburg Monarchy. Speaking the local languages, Serbian and Romanian, was important for contacts with the population in order to obtain information quickly about economic, geographical and political conditions. From top to bottom, these staff were very mobile, commuted between Vienna and the Banat, travelling throughout the region and along the border with the Ottoman Empire. Some were “floaters” and stayed only for a short time, others brought their entire family. Locals, who came mostly from farming backgrounds, were hired only for lower level posts at first, but that changed in the course of time.

Ups and downs

"The greatest challenge for the Habsburgs was whether and for how long they would have their backs protected to build a modern province”, emphasises the historian. The war against the Ottoman Empire (1737-1739) was a bitter setback and represented the “strongest disruption”. Much of what had been built up from 1718 onward was destroyed again by the invasion of the Ottoman army. “After the peace accord, the order of the day was reconstruction - sometimes starting from scratch. Those war and post-war years also represented an intermission in terms of personnel management”, explains Harald Heppner. There was still time for working on that until the year 1778 because then the bulk of the region was incorporated into the Hungarian part of the monarchy. Lessons to be learned: the development of a modern bureaucracy was successful, but was based on the sheer dedication of staff who needed to be competent, courageous, flexible and willing to take risks. Otherwise, the local climate alone would probably have driven them away.

Personal details Harald Heppner is a historian and Professor of Southeastern European History at the Institute of History at the University of Graz. He heads the Pro-Oriente Commission of Historians and holds several honorary doctorates from universities in Bulgaria and Romania. The publication on the FWF project "Personnel Management in a New Province: The Austrian Banat" will be published in 2019.

Publications