Colour – a link between art and medicine

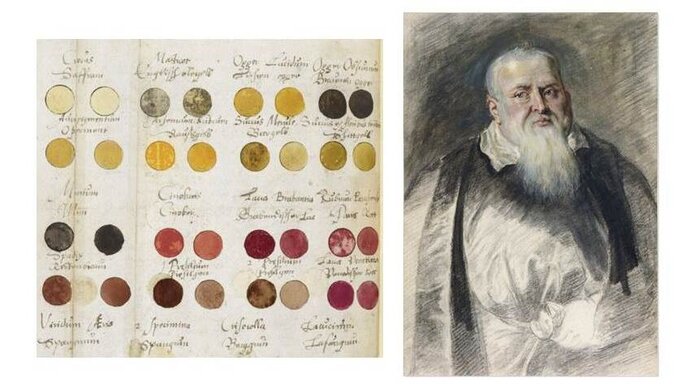

Nowadays, giving a urine sample is part of a standard medical check-up: the colour of the sample is still assessed in what is called uroscopy or “visual urine inspection”, a diagnostic tool that has been known since ancient times. The terms to describe the many shades, on the other hand, were defined much later. A man who played a key role in this was Théodore Turquet de Mayerne (1573-1655), a Genevan-born doctor of medicine and personal physician to the English King James I. “De Mayerne was a doctor, but he also painted. He worked with pigments and created colour recipes, which he discussed with well-known painters of his time such as Peter Paul Rubens and Anthonis van Dyck,” explains art historian Romana Sammern. In addition to his documentation of handwritten recipes for the royal family – e.g. for cosmetic products such as creams or lip care – these colour recipes have been handed down in an extensive collection, the Mayerne manuscript. This professional exchange between art and medicine, demonstrably benefitting both disciplines, took place in England at a time when both fields were going through a process of professionalization. In a project funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF, Sammern investigated the relationship between body and body image in the early modern period in both England and Italy. Pigments and other substances, including cosmetics, play a central role in this context. “I found it particularly exciting to explore the overlap between art, body care and medicine,” says Romana Sammern, who most recently held a Hertha-Firnberg position in the Department of Art History at the Paris-Lodron University in Salzburg.

Practice and theory go hand in hand

The interdisciplinary exchange had two effects: it demonstrated whether de Mayerne's colour recipes functioned in artistic practice and it also created theoretical foundations, including designations for shades of colour. It is also interesting to note that several substances were used in all three areas – art, cosmetics and medicine. One example is “lead white”: it had been used in cosmetics since the Middle Ages to lighten the complexion and was used for theatrical make-up until the invention of a lead-free alternative. In painting, artists used it, for instance, to create bright reflexes, and in medicine it was used to treat syphilis. Although the substance was the same everywhere, the areas of application were assessed very differently. Medical cosmetics or cosmetic dermatology (cosmetica medicamenta) was performed by doctors, at that time exclusively men, and enjoyed a professional – i.e. “good” – reputation. In contrast, beauty-enhancing cosmetics (ars decoratoria) was a female domain: especially in theological writings, such as those of the English clergyman Thomas Tuke (1580-1657), it was condemned as “bad” and a fraudulent enhancement of the natural appearance, as Sammern reports; it was also scorned because woman, God’s creature, became the creator of her own image through the act of using make-up.

In line with the respective body image

The art historian Romana Sammern undertook this analysis of sources about the relationship between body and image in England and Italy between the 16th and 18th centuries, because she was interested, among other things, in learning what physical beauty actually meant at different times and in different places. In the context of her research project she studied hundreds of sources. She was particularly fascinated by what these sources recommended in addition to pigments and other substances in order to adapt the human body to a given body image. Revealing information is provided by the book Gli ornamenti delle donne (The ornaments of women, 1562) by the physician Giovanni Marinello. It is one of the many “books of secrets” that were central to the dissemination of science know-how from the Middle Ages until the time when the natural sciences became firmly established as a discipline. The production of creams, skin care or instructions for hair dying or removal – cosmetics, in other words – was part of such know-how. As Sammern notes, Marinello's beauty canon is based on ideals from art: “He explains, for example, why and by using which techniques the human body can be modified in order to achieve an ideal body image.” A concrete example is the binding of body parts. Based on the ancient humoral theory, Marinello assumed that this influenced the flow of humours to such an extent as to change the shape of body parts.

Various influences on body image

According to Sammern, the body has been viewed and worked on like a sculpture, whereby "art has taken its lead from nature, i.e. the human body, and humans have been guided by the ideals of art”. Sammern’s research reveals that body images were strongly influenced by the exchange between doctors and artists. In Marinello's work, the connection between art theory, cosmetics and medicine is particularly striking. Sammern is not satisfied by the claim that applying make-up is a purely superficial embellishment. In her opinion, there is an exciting dualism of naturalness and artificiality underlying it, which can go as far as to include the “creation” of a person and the construction of a body image.

Personal details Romana Sammern is an art historian who gained her doctorate at the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Prior to her FWF-funded Hertha-Firnberg position at the Paris Lodron University Salzburg in the Department of Art, Music and Dance Studies, she did research at the Max-Planck Institute for Art History in Florence.

Publications