Climate archive in the ice

“The Elise Richter was a turning point in my scientific life”, is how Elisabeth Schlosser comments on the grant she received from the FWF in 2006. At that time she had been on the brink of leaving science for good. Why was that?

Two-class science system

Ever since 1992 – with short interruptions – the meteorologist from the University of Innsbruck has been working exclusively on the basis of fixed-term projects financed from third-party funds. A situation she had not anticipated: “I thought that at some point I would get an assistant’s post at the university. But apparently I'll be stuck with a third-party funding existence until the day I retire”, she notes. Not only does she have to keep writing proposals, but there are additional obstacles such as the ‘chain contract law’ limiting the number of consecutive temporary contracts researchers can conclude. The scientist regards this situation as exhausting and demoralising - and she even sees Austria as having a two-class science system: “As a scientist working with third-party funds you are a second-class person”, she says.

When Elisabeth Schlosser was on the verge of giving up this gruelling fight, she received the grant from the FWF’s Elise-Richter Programme for female scientists striving for a university career. “The FWF is the only institution that supports third-party funding scientists and encourages and appreciates them”, she states.

A welcome visiting scholar

The Richter grant enabled her to embark on her first research stay in Boulder, Colorado, where she found exactly the conditions and the support she sought. “That was heaven on earth! I was not a third-party funding creature but simply a welcome visiting scientist”, she enthuses in recollection. “Many people there work with third party funds, but you wouldn’t notice, because they are given exactly the same support and the same offices as those with permanent employment contracts”, the meteorologist explains.

Highlighting what is new and innovative

Since she has to earn her living by writing successful proposals, she invests a great deal of time and energy in her submissions. Based on her years of experience she would advise young scholars to highlight what is new and innovative about their project in their proposals, because she feels one cannot expect all reviewers to be experts in the respective field and to devote as much time to their reviews as desirable. Looking back on her 20 years of submitting proposals to the Austrian Science Fund FWF, she observes that there is much more information provided to applicants nowadays and mentions the coaching workshops of the FWF as a praiseworthy example.

Climate change hundreds of thousands of years ago

Since mid-2016 she is working on her current FWF-funded project, Atmospheric controls on stable isotopes in Antarctica, which investigates climate changes of the past. “In order to be able to make statements about future climate changes we have to understand the current climate system”, Schlosser says. Past climate changes provide valuable information in that context. But how do we get this information? While meteorological measurements have only been made for roughly the last 200 years, we know about past climate changes involving ice ages that occurred hundreds of thousands years ago.

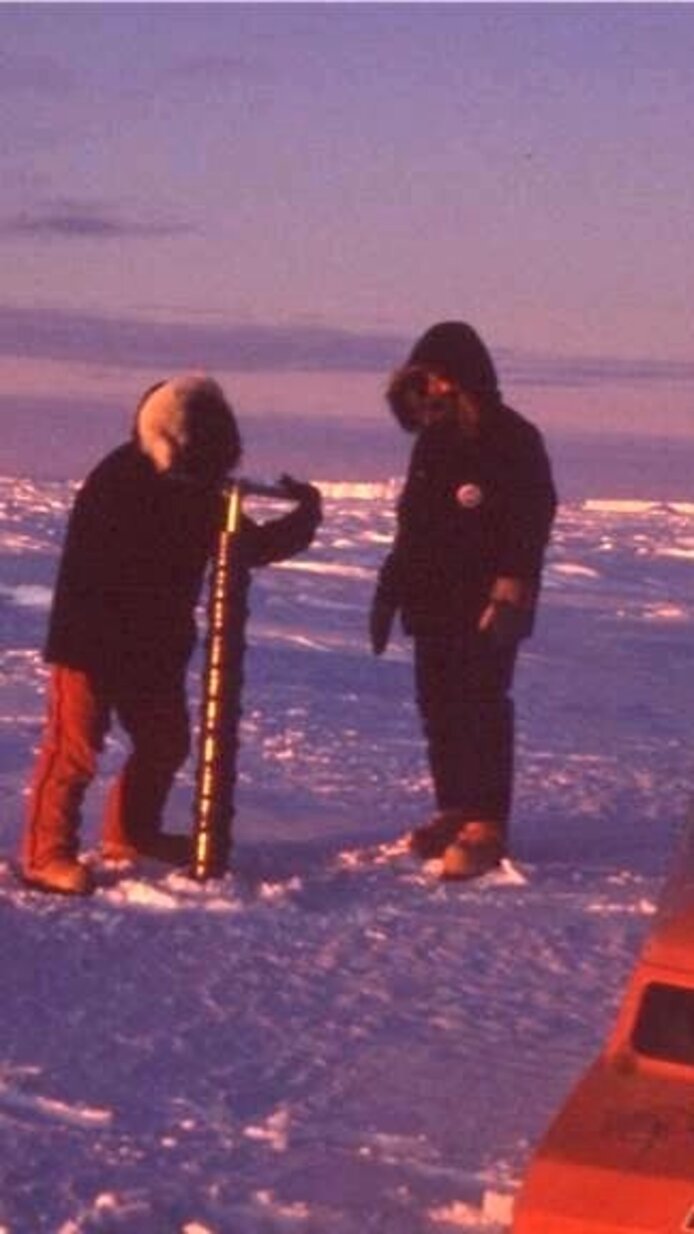

800,000-years-old ice

An important source of information is provided by ice cores drilled in Greenland and Antarctica. In these deep ice cores the climate of the past has been stored. They have a diameter of about 10 cm, can be up to 3 km in length and consist of ice that is up to 800,000 years old. Since drilling is only possible during the summer season – at temperatures between -45° and -25° – it takes several years to extract such deep ice cores.

Climate archives

Air bubbles trapped in the ice provide information about the composition of the atmosphere at the time when the ice was formed, for instance the levels of carbon dioxide, methane and other greenhouse gases. Further insights are gained by measuring certain physical and chemical properties, such as the dust content, salinity or electrical conductivity. “Such information can only be gained from ice cores”, says Elisabeth Schlosser.

Isotopes provide information about past temperatures

In order to reconstruct the temperature situation of past eras, the scientist measure so-called stable isotopes of water. Isotopes are different types of the same substance. There are, for instance, three types of oxygen: apart from ‘normal’ oxygen O16 there are two other forms, O17 and O18. The latter are heavier than O16 and have different physical properties. The ratio of these different types of oxygen depends on air temperature. “Until recently, only O16 and O18 were measured. New portable devices enable us now to also measure O17 which only exists in very small quantities”, Schlosser reports. Since water, and thus snow, is H2O, the scientists measure both the oxygen and the hydrogen isotopes of water vapour, water or melted ice. The new devices can not only be used to investigate ice and snow samples, but they can also continuously measure the isotope ratio of the water vapour that forms the basis of the snow and, thus, the ice. However, the relationship between the isotope ratio and air temperature is highly complex and cannot easily be derived from an ice core.. “The isotope ratio depends not only on air temperature, but also on the circumstances under which the snow fell that later turned to ice. Therefore, we investigate current snow and the meteorological conditions during snowfall under present-day conditions, where meteorological data are abundant. We study the atmospheric flow conditions as well as the origin of the water vapour and its transport paths to Antarctica”, Elisabeth Schlosser adds.

Field research in Antarctica

The coming winter season, the meteorologist will embark on her next expedition to Antarctica, where she will measure stable isotopes of water vapour at the German research station Neumayer. She will spend two or three months there and – weather permitting – sample snow every day. The Neumayer Station is situated in coastal Antarctica, where with an annual average temperature of -16°, the climate is significantly milder than in interior Antarctica.

“I love the mountains!”

Elisabeth Schlosser is particularly looking forward to this field research. After all, this nature lover’s choice of study was influenced by the perspective of being able to work in an ‘open-air laboratory’. “If I had to spend all my time sitting at the computer and running models, I would lose the joy of science”, the scientist says. Raised in the German town of Ratingen, situated between Düsseldorf and Duisburg, she started to study in Bonn. Turned back by the anonymity caused by huge numbers of students there, she switched to the University of Innsbruck, where she was able to pursue her special interest in glaciology, the study of ice and snow. It was not only the university that made her want to move there, but also the landscape. “I love the mountains! Where I was born there are neither mountains nor nature, it’s situated at the transition of steel industry to chemical industry”, Schlosser laughs. In her fourth semester she was already offered to participate in an expedition to the Antarctic, during which she collected data for her diploma thesis. She also had to give a talk about ice cores. “At the time, I wouldn’t have believed that this would be my profession someday”, Schlosser recalls with a smile.

“I don’t like Germans”

By now she has spent more than three decades in Tyrol and more than 20 years as an Austrian citizen. And yet, once in a while she is still called a Piefke, a derogatory nickname Austrians occasionally use for Germans. She has often heard Tyrolians say: “Actually, the Germans I know are all quite nice. But I still don’t like Germans.” In her first years in Austria she had many opportunities for demonstrating her sense of humour and repartee. “In Austria, you are never allowed to say what you think”, notes the 54-year-old scientist.

“If you say something negative, you will not be received well. But you must not say anything positive either, because the other person might be embarrassed.” At some point, she fell silent. This was a period she calls her “Austro-German compensation phase” in retrospect. After 20 years of keeping silent, she felt she wasn’t herself any more. “I then started to speak my mind again, only more kindly”, Schlosser laughs.

The bicycle and the mountains

But sometimes she is still moving on treacherous ground: “We are separated by our common language!” Schlosser jests and adds: “You think that you understand what people are saying, but they mean something completely different. What some people consider polite, others think is obsequious.” Nevertheless she has always felt at home in Tyrol with ‘her bicycle’ and ‘her mountains’. And she is not alone with her love for the mountains: her parents and siblings like to come and visit her, the only ‘Austrian’ in the family.

Best ideas on the mountain and on her bicycle

Her best ideas sometimes come to her mind on ski tours or on her road bike, reports Schlosser. This is why she finds it so regrettable that the publishing pressure does not leave enough time for reflection during work. “There are so many solitary fighters. Some are kept busy by their teaching obligations, others fight for money and publications”, she points out and quotes Nobel Prize laureates, who state that they would never have received the prize if they had been under a comparable pressure to publish.

Recharging in Boulder Schlosser would like to see the chain-contract paragraph in the university law abolished and also wishes for more recognition for third-party funded scholars: “People in permanent employment at a university find less and less time to do research. This is specifically what you need third-party funded people for”, she notes. Every year, Elisabeth Schlosser spends three months doing research in Boulder, Colorado, and several weeks in Tromsø in Norway. “That recharges my batteries!” Without her annual research trips she might have abandoned research altogether, the meteorologist states drily. She has often thought about possible alternatives. Schlosser passionately loves photography and writing: “I would really like to write for a road bike magazine and provide my own photographs for the articles as well”, is one of the ideas she mentions. But these are rather plans for retirement – fortunately, for the time being she will stay in science.

Elisabeth Schlosser is a meteorologist at the Institute of Atmospheric and Cryospheric Sciences (ACINN) of the University of Innsbruck, where she acquired habilitation status in 2010, and has been employed at the Austrian Polar Research Institute (APRI) since 2016. She studies ice cores of several kilometres in length to explore changes in climate and temperature across a period of several hundred-thousand years. Every year, her research takes her for several months to the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder, USA, and to the Norwegian Polar Institute in Tromsø.

More Information > FWF project: Atmospheric controls on water stable isotopes in Antarctica > Career development programme for female scientists Elise Richter