Between fear and hope

Researchers usually take a sober approach to their work and – with the exception of psychology disciplines – do not delve deeply into the realm of emotions. Hence one is justified in considering it “unusual” when a specialist in East-Central and South-Eastern Europe, together with an expert on Slovenia and an expert on Romania, join forces to capture emotions of a time long past.

“Between Fear and Hope. Rural Perspectives in the Age of the Great War” is the title of this research project based at the University of Graz, with the historian Harald Heppner as its principal investigator. “Our project explores the question as to the emotional state of the rural population in the period before, during and after the First World War,” says Heppner. According to Heppner, the rural population was always affected by wars inasmuch as it had to furnish supplies and provide soldiers for enlistment. “But war provokes not only fear, but also the hope that its consequences might lead to a better life for the individual.” The emotional situation of the rural population thus fluctuated between the two great poles of fear and hope.

Case studies from Slovenia and Romania

Two regions serve as case studies for the project: eastern Slovenia and parts of Transylvania. Both are peripheral, rural areas that belonged to Austria-Hungary before the Great War, but were handed over to Yugoslavia and Romania, respectively, after the war. The period under study begins around 1900 – “around then the effects of industrialisation and modernisation began to make themselves felt in the rural areas,” says Heppner - and it ends around the mid-1920s, when the post-war order had become well established. The essential question is how the rural population in the two regions felt in the first quarter of the 20th century and what their outlook on the future was.

In order to understand the emotional situation of people many of whom have been dead for 100 years, the researchers use a variety of different sources. First, there are personal sources, so-called “ego documents”, i.e. diaries or memoirs. Then there are archival sources such as gendarmerie reports or parish registers, and even government sources may reveal some feelings, taking the form for example of complaints to official bodies. Sources from authorities have the advantage that in times of war the state wanted to generate certain feelings, such as patriotism and perseverance, which meant the emotional situation of the population was always an issue.

Rich pickings and scepticism towards innovations

Search in the archives began with the start of the project in June 2019, including field visits, and the findings were richer than anticipated. “We were almost positively surprised by the wealth of sources,” says Heppner. The team analysed the sources found and filtered out any parts that had no bearing on emotional life. Finally, they made comparisons: did soldiers at the front feel differently from people who stayed at home in rural areas? Did women feel differently from men, young people differently from older people?

Due to a delay of half a year caused by the pandemic, the project has not yet been completed. But Heppner is already in a position to disclose a few findings with more outcomes to be presented at a symposium in June: “The future was unpredictable, then even more so than now. Rural inhabitants, whether they were at the front or in the hinterland, had to manage by themselves to get through these big changes.” According to Heppner, this was easier for those who stayed in their village, where the familiar context was preserved for a time, than for people who had to leave their homes, whether as soldiers or displaced persons. The rural population neither enthusiastically welcomed nor ignored the modernisation they were confronted with. “The rural population tends to be sceptical of innovations until they have seen how it will benefit them,” says Heppner. A certain reticence towards change was definitely observable.

Religion gives strength in uncertain times

There is no clear answer to the question as to which of the two feelings from the title of the research project was predominant. According to Heppner, fear had the upper hand initially, in the face of everything that descended on the rural population from outside and turned them into mere pawns. But there was also hope that their lives would get better. “Their hopes, however, did not rest on the authorities or fate, but on God.” The rural communities were still very much anchored in religion, as the historian notes.

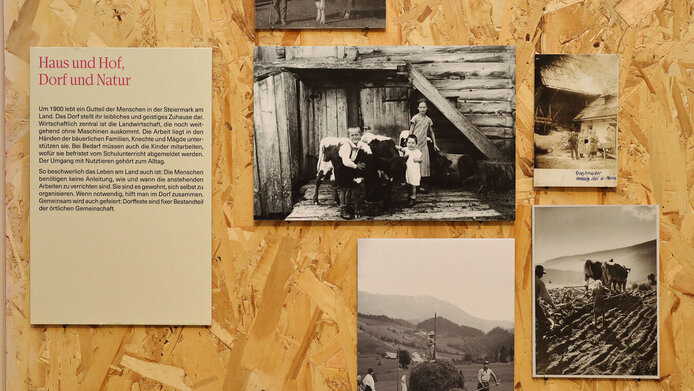

The research team is filling a gap with their project. Upon completion, the rural, emotional perspective will not only be presented at specialist conferences, but also made available to an interested wider public. An exhibition running until the end of October 2022 at the Museum of History in Graz, entitled “In einer zerrissenen Zeit. Das Dorf vor 100 Jahren,” transfers findings from the research project to the Styrian context. Exhibitions are also planned in Romania and Slovenia.

Personal details

Harald Heppner is Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Graz. He is a specialist in Southeast European history and the 18th century in the Danube-Carpathian region. Heppner studied history and Russian in Graz and research stays took him to Bucharest, Sofia and Moscow. In 1997 he took over the chair of Southeast European History at the University in Graz. Set to run until the end of 2022, the project “Between Fear and Hope. Rural Perspectives” receives EUR 353,000 in funding from the Austrian Science Fund FWF.

Recommended exhibition: In einer zerrissenen Zeit. Das Dorf vor hundert Jahren. Graz: Museum für Geschichte/Universalmuseum Joanneum, 29 April – 30 October 2022