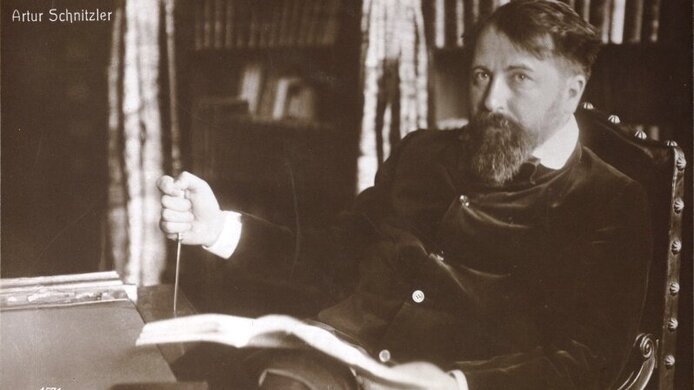

At Arthur Schnitzler’s desk

You do need about three months of familiarity with Arthur Schnitzler's handwriting to become halfway proficient at reading it, observes Konstanze Fliedl from the University of Vienna. Almost ten years ago, this literature specialist dedicated herself to a major project when she began editing the early work of Schnitzler, the seminal writer of Viennese Modernism. Schnitzler's handwriting, long considered indecipherable, but also the author's extensive estate of manuscripts and papers, scattered throughout Europe, were the reasons why no systematic analysis of the genesis of his works was conducted until the 21st century. Ten new volumes are now available, including the well-known plays Anatol and Liebelei (Flirtation), as well as the novella Lieutenant Gustl (None but the Brave). The genesis of these works is traced in detail, opening up new perspectives. – Almost as if one had been looking over Schnitzler’s shoulder when he penned them. “It's a genetic edition,” Fliedl specifies. This means that the volumes contain no interpretations nor an account of the history of literary reception – which would probably represent more than a lifetime’s work. Instead, the genesis of Arthur Schnitzler’s works till 1904 was meticulously traced, word by word, from first notes up to printing. Prior to 1904, Schnitzler wrote mostly by hand using a pencil, while later he almost always dictated his work aloud. Most of these early manuscripts are now in the Cambridge University Library, where they were brought to safety in 1938, when the German Wehrmacht marched into Austria. That part of his estate alone is estimated to encompass around 40,000 pages.

From notes to print

The latest edition – Reigen (La Ronde) is to be published very soon – will reproduce all preserved material in full-size facsimiles including transcripts. It depicts the entire writing process: crossed-out text, text flagged for deletion, overwrites, and so on. The edition also clearly reveals to what extent many manuscripts differ from the final print version. And if things remain unclear, for instance because the text is difficult to decipher, such uncertainties are also made discernible for the reader. The editions include versions of the works based on the first editions. “This is important because the paperback editions available to date contain many errors. That's why we established the texts based on the first print version, which was personally reviewed by Schnitzler,” says Fliedl. A lot of time and work also went into considerations as to how all this could best be presented typographically.

More information

https://www.arthur-schnitzler.at/historisch-kritische-ausgabe/

From the book edition to the digital age

The historical-critical edition was first published in print and as an e-book by De Gruyter. As a second step, Fliedl’s team used digital technologies to create a layout for the editions independently. In the final phase of this elaborate research project, which the Austrian Science Fund FWF has supported since its inception in 2010, this presentation of the data will be used for an online version. The researchers will be supported by expertise from the Austrian Centre for Digital Humanities (ACDH), where a project about Schnitzler’s correspondence is currently being developed, as regards the technical implementation. The digital tools offer the advantage of tracing the genesis of the texts in visual form. The novella Blumen is a good example, because it had a particularly complicated history with a great deal of material being reassembled and pages being re-ordered.

New take on the writer

The current edition of Schnitzler's early work is not only an enormous publishing achievement; it also provides new foundations for Schnitzler research. After all, free access to the various versions is expected to foster scientific exchanges. For the current project, Fliedl is planning a first-time digital text genesis spanning several works in cooperation with a British research team, which will focus on works Schnitzler created in the middle of his creative years. “For me personally, it was exciting to learn how much effort Arthur Schnitzler invested in the actual form, from the first pencil notes to manuscripts and to the print edition,” Konstanze Fliedl notes. As she sees it, one could describe his working process as an act of compression that benefited the composition. “Schnitzler is regarded as an 'impressionist', as someone whose writing was determined by his moods. Nothing could be further from the truth. In reality, he dedicated a great deal of hard work and craftsmanship to his writing."

Award ceremony and a stage reading

On the occasion of the book presentation of Reigen on 6 June 2019, a reading of this notorious play will be staged at the Burgtheater’s Kasino venue in Vienna. At the same event, the Arthur Schnitzler Prize will be awarded for the fourth time. This year the prize goes to the playwright and director René Pollesch.

Personal details

Konstanze Fliedl is a full professor at the Institute for Germanic Studies of the University of Vienna. She studied German language and literature, art history and theology and acquired her professorial qualification with work on Arthur Schnitzler. She has held several visiting professorships, including in Berlin and Zurich, and conducted research at Harvard and Yale. Fliedl is the president of the Arthur Schnitzler-Gesellschaft and her research focuses on the fields of editing, Austrian literature and literary criticism.