Ancient cemetery without pomp and glory provides new insights

“In a really simple grave we found food in the dead man's hand. A piece of bread perhaps? It was carefully placed there after his death, and the hand was arranged in front of his face so that he would have provisions in the afterlife,” relates Eva Christiana Köhler, describing a touching find. This is one of 218 graves which Köhler, an Egyptologist and archaeologist, and her team found in an unknown part of the “Necropolis of Helwan”. This excavation site on the eastern bank of the Nile, close to the present-day city of Helwan and about 25 kilometres south of Cairo, is considered the largest ancient cemetery of its time. As finds have shown, it enjoyed its heyday between 3,300 and 2,700 BC, which corresponds to the Central European Bronze Age. It is not only its size, however, that makes it unique: the necropolis is mainly occupied by ordinary mortals, members of the ancient lower and upper classes of Memphis at the time when it was the capital of Egypt. “The graves allow us to look at the grassroots of urban society and to understand it better,” explains Köhler, who has been head of the Institute of Egyptology at the University of Vienna since 2010.

Rescued for posterity at the last minute

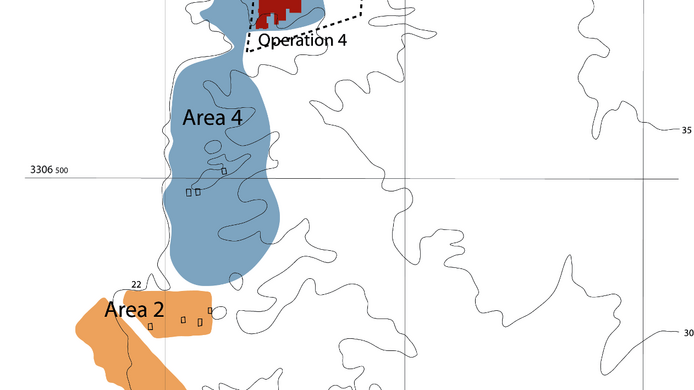

Several years of excavation work on the previously unexplored area rewarded the researchers with the discovery of a total of 218 graves, 229 corpses, about 70,000 plant and 13,000 animal remains, as well as more than 150,000 pottery fragments, hundreds of vessels and about 2,000 other artefacts. According to Köhler, the field of about 7,000 square metres is only a small part of the original excavation area. First excavations there were conducted in the 1940s under the direction of the renowned Egyptian archaeologist Zaki Youssef Saad (1901-1982). At that time, more than 10,000 graves were uncovered on an area of around 100 hectares.

Köhler began her research in 1997, which initially consisted in re-excavating, locating and cataloguing some of Saad’s finds using modern methods. Her own excavations on an unexplored part of the cemetery completed the excavation work. There were several occasions when this archaeological site narrowly escaped the fate of becoming inaccessible forever because it was urgently wanted as building land: “In 2006, one day after we had completed the excavations, the inhabitants of the neighbouring village came to mark out plots for development. My Egyptian colleague noticed this and immediately told me about it,” recalls Köhler, who was a lecturer at Macquarie University in Sydney at the time. She talked to the Egyptian authorities and since then, the entire site of around 20 hectares has been under an Egyptian preservation order and is surrounded by a wall for protection. In the context of a research project funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF she documented and analysed what came to light during the recent excavations.

The individual was highly regarded

“At a distance of 7 to 8 kilometres as the crow flies, the well-known – pharaonic – Memphis is too far away. The common people, as we find them in the Helwan necropolis, were buried close to the place where they lived,” explains Köhler. From this it follows that the first city of Memphis, whose exact location is still unknown today and which existed before the pharaohs, must have been much closer to the necropolis. A central factor for the work of the archaeologists is the “burial effort”, which is always proportionate to the socio-economic means of the deceased. The finds showed that all social strata put a great deal of effort into burials, within the limits of what was possible. A standard burial included a burial pit or underground facility, ceramic vessels for food and personal objects owned by the deceased. “Moreover, all grave sites were very tidy. Even for the poorest of the poor, who were laid to rest wrapped in a reed mat, they dug a pit and very delicately and carefully placed the body there,” says Köhler. The anthropological investigations also revealed that the people were generally quite healthy and did not exhibit any symptoms of nutritional deficiencies. It should be emphasised that the individual was of great importance in every social class. Every person – man, woman or child – was buried in their own grave together with everything that constituted their identity.

High-level stone working skills found early on

On the basis of the quantity, quality and material of the objects in a grave, the experts can cautiously assess to which social class the deceased belonged. In the necropolis of Helwan, the researchers only rarely found metalwork, valuable imported goods or semi-precious stones, as they are commonly found in elite tombs. Graves of people from lower social strata contain mainly objects of material culture, which they actually used during their lifetime. Those who belonged to a higher class used the medium of writing to express their identity. On a total of 50 grave reliefs the researchers found pictorial representations, names and professional titles, some of which are on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. “Their quality, the high degree of precision, the aesthetics and individuality of some of these is amazing. That's why we now know that the artistry associated with the pyramid-building age has its origins in pre-dynastic times,” Köhler notes. The same applies to the level of engineering: as one burial site demonstrates, people already knew how to mine stone blocks weighing two and a half tons, transport them safely to their destination and place them in the burial chamber to the nearest centimetre several centuries before the pyramids were built.

New sources for 2nd Dynasty

The graves of the Helwan necropolis are also of interest in chronological terms: in the historical chronology of Egyptian history, the periods of reign of the pharaohs (dynasties) are important points of reference, which is why royal tombs are a central source. Little is known, however, about the 2nd Dynasty. Its duration could not yet be determined exactly and is estimated at between 140 and 220 years. “What is exciting is that the necropolis in Helwan provides a huge record of material culture, and the 2nd Dynasty is very well represented. So now we can tell that it had five phases and had a longer rather than a shorter duration,” explains Köhler, who is currently researching the royal tombs in Abydos with the German Archaeological Institute in Cairo. Only the synchronisation of the different historical sections enables the experts to delimit a precise time span. Several finds from the necropolis are on display at the new National Museum of Egyptian Civilization, parts of which are already open, and much of what has been found will also be made accessible to the public in the Grand Egyptian Museum, which will probably open in 2021, and not in 2020 as scheduled, owing to the corona pandemic. There can be no doubt that tombs of common people are great sources of information and of enormous value for research and culture in order to better understand early Egyptian societies in all their facets – from beggars to pharaohs.

Personal details Eva Christiana Köhler is an Egyptologist and archaeologist. In 2010 she became head of the Institute of Egyptology at the University of Vienna. Before her appointment in Vienna, the German-born scholar had been a lecturer at Macquarie University in Sydney for over a decade. Several excavation projects have taken her mainly to Egypt and the Middle East. The excavations in Helwan were made possible under an Australian concession and, until 2011, with Australian funding. The Austrian Science Fund FWF has been supporting the research into the largest ancient cemetery in Ancient Egypt since 2014.

Publications