When food is the enemy

Sometimes it begins in the school yard that body weight suddenly becomes an issue. Who weighs how much, which girl is the thinnest? Young people are starting to be concerned about nutrition and calories and step on the scales more and more often. Eating disorders usually develop very gradually, mostly affecting girls – and the girls are getting younger all the time.

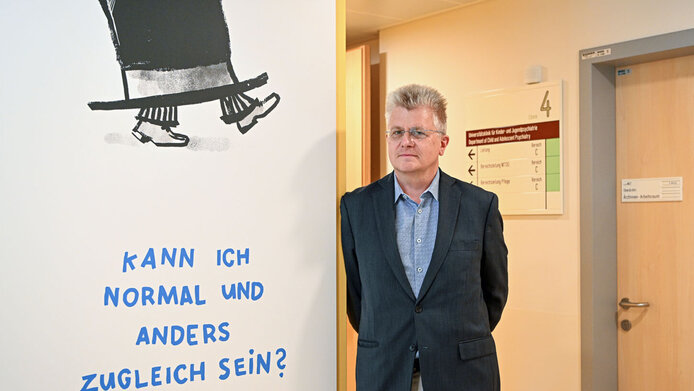

Andreas Karwautz is well placed to confirm this trend. He is a psychotherapist, child and adolescent psychiatrist, and founder and director of the special outpatient clinic for eating disorders in children and adolescents at Vienna General Hospital. “In the past, on average we used to have 14-year-olds with full-blown anorexia, but today they are often as young as 12,” he reports, describing a development that has been accelerated by the pandemic. His observations are supported by studies from Sweden and Germany. Tragically, the younger the children are, the more serious and far-reaching the consequences of the disease will be for body and mind.

The younger, the worse the long-term consequences

In the case of anorexia, the organ systems switch to survival mode and the body down-regulates all functions, slowing down blood pressure and heart rate. The brain is undersupplied, the patient becomes tired, unfocused and depressed. Anorexic children stop growing because growth hormones are suppressed, which is also problematic for bone development and can cause osteoporosis later in life.

Some girls do not do not start menstruating or their period stops for a long while. In particular the psychological consequences of an eating disorder may affect sufferers for the rest of their lives. Anxiety can turn into long-term anxiety disorders, depression can persist for a lifetime.

Number of people seeking help in the pandemic increased

In addition to seeing patients with eating disorders getting younger, Karwautz has also noticed the number of people seeking help in his outpatient clinic increasing significantly over the past two years. Nonetheless, he thinks it is an oversimplification to conclude that the incidence has increased. In fact, he believes that those who are seeking help now were already affected before the pandemic. “The pandemic has made the number of unreported cases more visible,” he says. And that number is high.

Three in four sufferers do not seek help

Karwautz makes reference to the representative, Austria-wide study Mental Health in Austrian Teenagers (MHAT), which he conducted as of 2013. Covering 2,500 schools of all types in all nine provinces, the study concluded that 75 per cent of all children and adolescents affected by eating disorders never seek help. “Those who were already ill before felt so much pressure in the pandemic situation that they had to seek help,” says Karwautz, and he adds that this also applies to other “silent” disorders such as depression and anxiety or obsessive-compulsive disorders. They have all become more visible in the last two years.

Anorexia, binge eating, bulimia

Eating disorders affect about eight per cent of all children and adolescents in Austria, especially girls between the ages of 10 and 18. The three most common forms are anorexia nervosa, bulimia and binge eating disorder. Then there are less common forms such as food refusal, which is mainly found in younger children between the ages of one and seven. These children will only eat certain foods or refuse to eat at all. According to Krawautz, there is an inherent destructive dynamic: “This is comparatively harmless, but the power struggles between child and parents can escalate to the point of physical violence.”

Binge eating and bulimia – three in a hundred get treatment

Three per cent of all children and adolescents in Austria are diagnosed with binge eating disorder or bulimia nervosa. In both disorders, those affected suffer recurrent episodes of binge eating with loss of control and subsequent feelings of guilt. Bulimia patients additionally apply methods of weight control for fear of gaining weight. These range from vomiting and laxatives to high-risk methods such as reducing the amount of insulin in diabetes 1 patients.

Anorexia is female

In Austria, 0.5 to 1 per cent of children and adolescents between 10 and 18 years of age undergo treatment for anorexia, the constant feeling of being too fat, which causes those affected to stop eating. Karwautz estimates that 95 per cent of sufferers are girls. There are several reasons for this high share. First of all, girls undergo more severe hormonal changes during puberty than boys. While adolescent males gain weight primarily in the form of muscle mass, it is the percentage of fat in the total body mass that increases in girls. Another factor is socialisation, since it is considered an unwritten law for women to be slim. Based on his 30 years of experience Krawautz specifies, however, that if men are affected by anorexia, they suffer particularly severely.

Special outpatient clinic – mainly anorexic girls

Andreas Karwautz was a trailblazer when he founded the special outpatient clinic for eating disorders in children and adolescents at the Vienna General Hospital (AKH) in 1993 “against a lot of resistance”. The main trigger for this step was his first contact as a young assistant doctor with an anorexia patient: “How do I establish contact with a patient who hardly speaks anymore because words have simply expired in this emaciated body? That was an important experience for me,” Karwautz recalls. Girls with anorexia make up the majority of the children and adolescents that Karwautz and his team have cared for over the years, mainly because those affected by anorexia are often the most severely ill and therefore more likely to receive treatment. Bulimia and binge eating disorder usually occur in slightly older individuals who no longer fall under the scope of child and adolescent psychiatry.

Causes and risk factors

Most eating disorders in children and adolescents are triggered by the fear of being overweight and scorned by others. The underlying causes are complex and include many risk factors. Depending on the individual constellation, these factors can tip the scales whether or not someone will fall ill at a certain age in the presence of certain triggers. “Causes of eating disorders are neither simple nor monocausal – the models are always multidimensional,” notes Krawautz. Besides biological factors, psychological, psychosocial and sociocultural aspects are of relevance in the development of the disease.

Anorexia nervosa: 60 per cent genetic

Anorexia nervosa is a strongly biological disease and its heritability lies at almost 60 per cent. Large so-called genome-wide association studies, in which the Medical University of Vienna is also participating, have been able to identify hereditary disease risks associated with anorexia, but also bulimia and binge eating disorder; this is true especially in areas that are also relevant for autoimmune diseases. “What we found to be relevant were gene sections that play a role in neurotransmitter systems for hunger, satiety and mood,” explains Krawautz.

Perfectionism, lower self-esteem

In the psychological and psychosocial domains, empirically reliable data indicate that combinations of perfectionism, lower self-esteem, fear of losing control, trauma, avoidance coping strategies and cultural influences play a role. According to Krawautz, almost all anorexics display one crucial characteristic: they do not know how to react to problematic situations. In medical terminology, this is called avoidance coping – problems are being avoided or denied.

A focus on standards and performance, the western ideal of beauty

Unhealthy family structures can also make someone ill. Some factors such as fierce conflicts between parents, a heightened focus on norms and performance standards, impulsive actions or lack of emotions in the family environment can favour bulimia. The cultural influence of a Western ideal of being slim and its dissemination via social media plays just as important a role. Particularly young girls measure themselves against their role models on social media. Studies in the Asian region have shown that being concerned about one’s weight is more frequent in regions where the influence of the media is high and that there are fundamental differences between urban and rural environments.

Risk increases with access to Western media

A recent longitudinal study by Jackson and Chen from 2011 on social change in China shows that the risk factors for developing an eating disorder in adolescence have become similar to the known factors in the European and North American region as a consequence of being confronted with the Western ideal of slimness via access to Western media.

Higher risk in conurbations and among the upper classes

Comparative cultural studies also show that in non-Western countries, girls and young women are more likely to develop an eating disorder if they are exposed to Western body norms, live in urban centres, have previously lived in Western countries and have a high socioeconomic status. While the prevalence of eating disorders is much lower in developing and emerging countries, it is on the rise even there. Studies on migrants (including this study) show a so-called “culture-change syndrome”, meaning that young women are more likely to develop body image problems and eating disorders after moving to a Western culture. The connection with the Western body ideal is primarily seen in bulimia. Anorexia nervosa seems to be culture-dependent only to a very limited extent; studies in non-Western countries have shown similarly high prevalence.

Binge eating among black and white women equally prevalent

Several studies of African American women in the USA and the Caribbean suggest that there is also an ethnic component to the development of anorexia. Although these women are exposed to a similar degree of media pressure to be slim as white women, they develop anorexia extremely rarely and bulimia less frequently than white women. On the other hand, binge eating disorders are equally prevalent among black and white women. There is an evident connection with the availability of food that is cheap but of low nutritional quality such as burgers and sugar-loaded soft drinks.

Not a 20th-century phenomenon

History shows that eating disorders are not a 20th-century phenomenon. Apart from early forms of being underweight deliberately among fasting people driven by asceticism and mysticism, who pursued an ideal of female piety or even holiness and had a religious motive, modern forms of eating disorders such as anorexia and bulimia were already spreading in Europe in the second half of the 19th century, and they were first described as early as 1694.

Empress Sisi – dieting and excessive sports

The Austrian Empress Sisi is a famous example. At a height of 1.72 metres, she sometimes weighed no more than 50 kg. With diets involving oranges, eggs or milk, the empress kept her weight constantly low and brought her waistline to a very narrow 46 centimetres. She also exercised excessively: her daily regimen included up to eight hours of horseback riding and gymnastics.

Increase in anorexia in the 1960s and 1970s

In contrast to religiously motivated fasting, eating disorders are characterised by an excessive concern about one's own body weight, accompanied by measures to control body weight. It only became a publicly known disorder in the 1960s and 1970s, when the incidence of anorexia increased.

What alarm signals should parents look out for?

“If the child keeps finding reasons why they are not eating with the others, if food disappears but then is found in the rubbish bin – this is when you should become alert and start asking questions,” notes Karwautz. “Adolescents are masters of dissimulation and they can keep other people – especially parents – at a distance, so you have to verify if their behaviour is age-appropriate or if there is more to it than that.”

Clear symptoms of an eating disorder include an increased interest in food composition and caloric content, avoiding or refusing main meals, frequent weight checks, feeling overweight despite being in or below the normal range, excessive sport, increasing performance orientation and isolation, and the absence of menstruation.

Eating disorders – core competence of psychiatry

According to Karwautz, the special outpatient clinic at the AKH sees its primary remit in looking after severely ill patients when things become complex and difficult. He would like to see young patients consult experts in child and adolescent psychiatry at an earlier stage, so that they can avoid the long path of chronic disease. Eating disorders are a core competence of his field: “Anorexia quickly becomes chronic. If you seek out psychiatric help straight away, you might be able to stop an illness quickly and professionally and save yourself a long and painful journey.” Karwautz notes that a stigmatisation of psychiatry, sometimes observed in paediatrics or other disciplines such as psychology and psychotherapy, is detrimental to successful treatment. He sees the need for all fields to cooperate.

Psychiatry – an “endangered species”

The psychiatrist is bothered by the fact that his field still suffers from a stigma. “Psychiatry has always concerned itself with the psychosocially and socially disadvantaged and with the severely ill: people who are addicts, suicidal, psychotic, and severely chronically ill. The majority of patients with mild depression and mild anxiety disorders are also looked after by all kinds of other professions. Psychiatry is the end of the line,” Karwautz says. He objects to this stigmatisation and calls providers of psychiatric services an “endangered species”. It is often the poor, the socially disadvantaged and the seriously ill, who cannot afford psychotherapy. And he notes that psychiatry in particular is highly integrative. “No medicine works if you don't talk to the patient,” is Karwautz’s credo.

Becoming accustomed to the disease

One of the reasons why eating disorders can relatively quickly become a chronic problem is the role played by habituation. Studies show that the disease gives patients a sense of security and self-confidence and makes them feel strong. Some even identify with the disease and refer to themselves as “anorexics”. It takes years of therapy for them to develop a new identity. And what remains when the disease is gone? Karwautz describes it like this: “During treatment, the young people have to find something that makes them feel safe and strong, so that they can move forward without the disease.”

“We would need twice as many beds”

In order to be able to treat more patients, more resources would be needed. Karwautz is saddened by the situation in Austria, where the field of child and adolescent psychiatry is dramatically underprovided. “We would need twice as many beds in child psychiatry in Austria, and even more than that in Vienna.”

This statement is based on figures collected by the Austrian National Public Health Institute (GÖG). Karwautz criticises the fact that he and his team have just eight beds available for the whole of Vienna: “We need facilities in conurbations that are tailored to requirements of these patients.”

Therapy – specific and multidisciplinary

At present, about 70 patients with anorexia are being treated in the special outpatient clinic at the AKH. In the case of younger children with eating disorders, treatment starts with the parents. In systemic therapy, the therapists work on communication in order to resolve the power struggles. In the case of adolescent anorexia patients, the therapy involves both sides. MANTR-a is a therapy specifically tailored to anorexic adolescents. Parents, who are often overwhelmed and desperate, are offered a support programme called Succeat, which is very popular. If no weight gain is achieved during the first months of treatment, the young people are admitted as inpatients and receive multidisciplinary care with measures such as psychotherapy, body therapy, occupational therapy, nutritional counselling; there are also cooking groups and critical discussions of social media. “The more specific the therapy, the better. It requires experts who are knowledgeable about adolescents and eating disorders. Such people are rare,” Karwautz says wistfully.

Therapy in Austria not sufficiently evidence-based

Unfortunately, there is a shortage of therapists in private practice who meet these requirements. Karwautz sees a basic problem of the situation in Austria in the fact that it is not geared to evidence-based therapy. “The Austrian health insurance pays a small subsidy for each form of therapy, regardless of whether there is scientific evidence of its effectiveness in the respective clinical picture. However, preference should be given to therapies that have been shown to work for this disease and this age group, and these should be paid for in full,” Karwautz says, and he highlights the German system that could serve as a model.

Connection between anorexia and intestinal flora

Karwautz expects a study he is currently conducting with funding from the FWF into the connection between anorexia nervosa and intestinal flora to result in a side-effect-free type of therapy using probiotics. The intestinal flora of anorexic patients is severely altered by their pathological diet. The diversity of the microbiome is reduced and it is in deplorable condition. Previous studies have shown that the intestinal microbiome does improve when normal weight is reached, but it is not fully restored – not even several months after full recovery. The reason for this is as yet unknown. The connection between the intestinal flora and diseases such as depression, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia and autism has been scientifically proved, and probiotics are already in use in this context.

Probiotics against anorexia?

Karwautz expects this double-blind controlled placebo study on anorexia to deliver many important answers. What happens when the patients gain weight again? In addition to the genetics of the intestinal microbiome and blood parameters, the study uses functional magnetic resonance to examine exactly what changes in the brain. “If you regain a good balance of the intestinal flora by administering probiotics, this should have an impact on both depressiveness and anxiety as well as on the eating disorder symptoms per se.”

Insights are gained where fields interface

Karwautz sees one of his most important concerns realised in this study: reuniting fields that are normally separate, such as psychology, psychiatry and neuroscience. “Good specific psychotherapies always take neurobiological findings into account. This is particularly obvious in eating disorders, because they involve massive mind-body interaction.” He likes these border areas and is convinced: “New insights are gained at the borders between fields.” Encouraging interaction at every level is one of his great talents: 2023 will see the thirteenth multidisciplinary “Vienna Congress on Eating Disorders” which he organises together with the clinical psychologist Gudrun Wagner. This conference is held every March at the Vienna AKH, and participant numbers are rising every year.

Therapy success rates at 80 per cent

Of the approximately 1,400 patients Karwautz and his team have looked after so far, 80 per cent have been cured. The psychiatrist sees an important criterion for this track record in case management. “We stay in touch with the patients and their families throughout the entire therapy and during follow-up care.” He warns that one must not expect quick fixes. Success needs patience and – especially in psychiatry – the patient's trust. Karwautz sums it up like this: “The work is done by the patient, I am a co-worker.”

“You have to like people”

“You have to like people,” he repeats several times, and you can feel his passion for the job and how important his patients are to him. His motivation is tireless: “In child and adolescent psychiatry we are dealing with people in a very dynamic phase of life where we can really still make a difference. If you do it right, it works, and if you experience that often, the resulting sense of confidence communicates itself to the patients. People are very grateful when they realise that someone is knowledgeable about this illness and the processes it involves.”

Prevention – building up self-esteem

But what can be done to prevent the development of an eating disorder? Since it is known that patients with eating disorders have difficulties dealing with problems, denying or avoiding them, this is the target area for prevention programmes, which involve continuous training for strengthening personal resources such as self-esteem, self-assertion, coping strategies and stress management. “If such training were offered continuously – for example in the context of schooling - many would not slip into an eating disorder in the first place,” Karwautz says with reference to internationally proven examples.

Personal details

Child and adolescent psychiatrist Andreas Karwautz is a researcher at the Medical University of Vienna. He is the founder and head of the multidisciplinary special outpatient clinic for eating disorders in childhood and adolescence at Vienna General Hospital (AKH). During his training as a psychotherapist, he studied human medicine at the Medical University of Vienna. He is a specialist in psychiatry & neurology, a professor of child and adolescent psychiatry, and a long-standing senior physician at the AKH’s Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

Karwautz’s research focus lies in all areas of eating disorders: risk, genetics, aetiology, clinical aspects, personality and therapy. From 1997 to 1998, this native of Vienna held an Erwin Schrödinger Fellowship funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neurosciences at King's College Hospital in London. In a study currently funded by the FWF, he is investigating the interaction between intestinal flora and the brain in anorexia nervosa, with the aim of developing a new therapy using probiotics.