When cancer invades the brain

While we know increasingly more about cancer, getting the diagnosis is still scary. One of the reasons why cancer places such a heavy burden on the body is its ability to spread throughout the body via the blood and lymph channels. When cancer cells migrate into other tissues and divide uncontrolled, they develop offshoots of the original tumor (metastases). In reality, however, this process is far more complex, as the tumor cells interact intensively with their environment – including immune cells that are supposed to protect the body from disease.

“Metastases can result in organ failure, which is one of the most common causes of death in cancer patients. Due to the unique tissue architecture of the brain, metastases in this part of the body are a particular challenge,” explains Klara Soukup, a cancer researcher who was involved in a recent publication in the science journal Cell by Johanna Joyce and her team at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland. This research group has specialized in investigating metastases in the central nervous system. An Erwin Schrödinger Fellowship from the Austrian Science Fund FWF enabled Soukup to spend a postdoctoral research stay there, which led to the discovery that tumor cells that invade the brain manipulate the body's own immune system.

When tumor cells migrate

“The formation of metastases can be thought of as being like a journey,” is the image Soukup uses to describe the process. At the beginning of the disease, mutated cells multiply in an initial tumor (primary tumor), from which they are able to migrate in later stages. Brain metastases usually develop from cancer cells that have started in a tumor of the lung, breast or skin, for example. Brain tumors are often only noticed when their growing size increases the pressure in the brain and causes strong headaches or other neurological symptoms. “However, there is a lot to be said against the successful formation of a metastasis. This is because a cancer cell has to be able to leave its unit/conglomerate and attach itself to another location despite the extreme mechanical forces occurring in the vessel,” explains Soukup.

Even if the cancer cell finds its way into another organ, it is demanding to survive and divide there. This is why only a small fraction of the countless cancer cells that start their journey through the body form metastases. There are factors, however, that favor the spread of cancer. Soukup and the team at the University of Lausanne have investigated one such factor in the case of brain metastases.

Cancer therapy

Immunotherapies have been used with particular success in the treatment of various types of cancer. These therapies strengthen the body's own defenses by adapting certain aspects of the immune system and activating T-killer cells that can destroy the cancer cells.

Manipulated immune cells interact with metastases

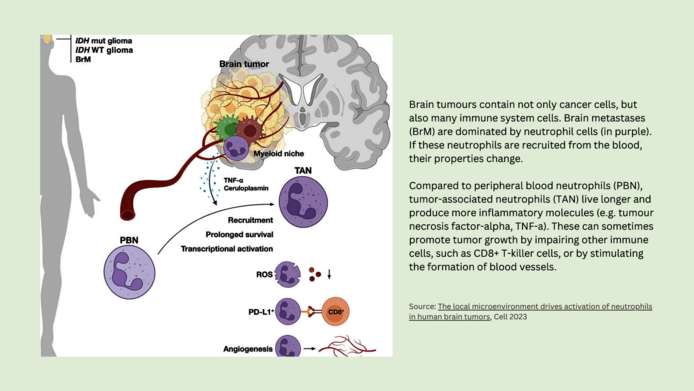

All tissues in the human body are different, and the brain's environment also has its unique characteristics. One of them involves the oxygen supply and nutrient composition, so that invading cancer cells have to adapt their metabolism and cannot colonize without support. In their research project, Soukup and the Swiss team examined samples of brain metastases that had been surgically removed from cancer patients. They discovered that a certain cell type was conspicuous by its frequent occurrence. These cells were neutrophils, the first responder cells of the immune system.

“For a long time, researchers assumed that there were hardly any immune cells in the brain. But Johanna Joyce's laboratory published the first systematic studies on immune cells in human brain tumors,” notes Soukup. Further analyses of around 200 biopsies showed that the tumor cells send out signals that reprogram the immigrated neutrophils. Under certain circumstances, their altered activity can contribute to tumor growth – for instance by stimulating the formation of blood vessels that supply the tumor and by dampening the immune response against the harmful cancer cells.

A tumor’s neighborhood

For several years now, cancer research has focused on the interactions in the immediate environment of tumors. This is an interesting issue, because tumor cells adapt the so-called tumor microenvironment in such a way as to optimize their chances of survival. “Our project has shown that tumor cells in brain metastases actively send out signals to attract and manipulate neutrophils,” says Soukup. The tumor cells use certain messenger substances to reinforce the inflammatory reaction of the neutrophils and prolong their lifespan, encouraging properties that sometimes benefit the cancer and not the immune response.

Neutrophils make up the majority of white blood cells in human blood. Under normal circumstances, they are tasked with initiating the immune defense against pathogens such as bacteria as first responders. They do this by releasing toxins against the pathogens and sending inflammatory signals to the immune system. “Neutrophils trigger powerful inflammatory reactions that are non-specific, which is why they can also damage the surrounding tissue. We were struck therefore by how many of these cells we found in the brain metastases. The question arose as to why they had migrated there in such large numbers,” says Soukup, explaining the impetus for the research project.

News from cancer therapy

In recent years, immunotherapies have been used with particular success in the treatment of various types of cancer. These therapies strengthen the body's own defenses by adapting certain aspects of the immune system and activating T-killer cells that can destroy the cancer cells. However, the effectiveness of the therapies can be impaired by processes in the tumor's microenvironment, for example by maladjusted neutrophils.

“Thanks to new therapies, people can now survive longer with cancers that used to be a death sentence,” says Soukup. “But the longer a tumor remains in the body, the greater the likelihood of metastases and the more difficult the therapy becomes.”

Personal details

Klara Soukup conducted her doctoral research at the St. Anna Children's Cancer Research Institute in Vienna before moving to the University of Lausanne in Switzerland as a postdoctoral researcher on an Erwin Schrödinger Fellowship from the Austrian Science Fund FWF. She now works at the university in the field of science communication. The project “The role of neutrophil cells in brain metastases” was awarded some EUR 70,000 in funding from the FWF.

Publication

Maas R.R., Soukup K., Fournier N. et al.: The local microenvironment drives activation of neutrophils in human brain tumors, in: Cell 2023