What really makes nations tick: checking clichés about climate and welfare

Do Nordic countries have a higher share of inhabitants like Greta Thunberg, who are prepared to accept severe restrictions in order to avert the climate catastrophe? Or is it people living in hot southern Europe who view the developments with greater concern? Do the Russian population care at all about their CO2 emissions? And why is it so easy to get political currency out of the concept of “our money for our people” in Austria? The international PAWCER study “Public Attitudes to Welfare, Climate Change and Energy in the EU and Russia” analysed attitudes and contextual data on issues of future relevance across a number of countries in 2016. The study is based on data from the biennial European Social Survey (ESS). Representative samples of the population were also surveyed in 2016 concerning the welfare state as well as energy security and climate change. The Austrian Science Fund FWF was involved in the co-financing of this project in the context of the European ERA-NET programme.

Similarities and trends between Europe and Russia

Marcel Fink, a political scientist at the Institute for Advanced Studies and principal investigator in the project, presents results from the analysis of the survey and contextual data for the countries concerned: “Even before policy-makers started to pay greater attention to the topics of energy security and climate change, the survey collected data for cross-national research. As concerns the welfare state issue, we were able to make comparisons along the timeline and gain a deeper understanding of conflicts and identities.” When it comes to public attitudes, international data often present problems in comparability, which PAWCER was able to eliminate. In the representative social survey, a total of almost 45,000 people were interviewed in 23 countries, 2,000 of them in Austria.

East-west gradient in energy issues

The survey used questions that had been solidly pre-tested in order to ensure they would be understood in the same way everywhere, in the EU member states as well as in Russia. In the context of the global climate debate, the survey sought to identify possible convergences between different political systems and comparable perceptions of the problematic issues. Regarding climate change, the level of concern was lower in Russia and other eastern European countries such as the Czech Republic, Estonia, Lithuania and Poland than in most western and southern European countries. “On the other hand, there were relatively bigger concerns along an east-west gradient about the affordability and security of energy and heating supplies than there were about the 'right way' to use energy. This suggests a difference in the social situation,” Marcel Fink explains.

The survey acts as a kind of cliché check, its questions aiming to find out what really makes nations tick and what we merely assume about each other. In questions about self-efficacy, i.e. to what extent people believe that they can contribute to counteracting climate change, Russia has the lowest level of agreement among all countries surveyed. Austria occupies a middle position in terms of concerns and self-efficacy. Concerns about climate change were more pronounced in Portugal and Spain, i.e. southern European countries, but also in Germany and France. The Nordic countries are in the lead when it comes to perceived self-efficacy, with mobilisation around climate issues certainly at a higher level now than in the 2016 survey.

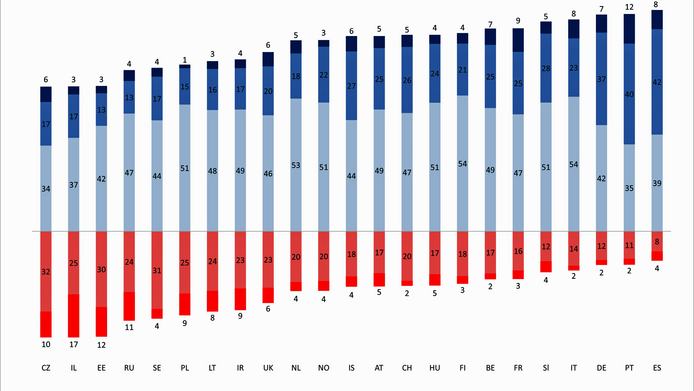

Our money for our people

Marcel Fink notes that, with a view to state-provided welfare, respondents in many eastern and southern European countries, where material inequality and unemployment are relatively high, consider the state should bear a major responsibility for mitigating such inequalities. In strongly developed welfare states such as in Scandinavia and western Europe, respondents do not perceive this with the same degree of urgency. Support for systems that benefit everyone, such as old-age provisions or a universal basic income, is at its strongest where the material standard of living is comparatively lower and social inequality is therefore relatively high.

When it comes to the question, however, of whether there should be generous benefits for the unemployed or immigrants, the respondents are often more restrictive in those countries where the welfare state is less developed. This can probably be explained by the concern that such benefits would then leave smaller resources for measures that benefit everyone. “Interestingly, 'welfare chauvinism' towards newcomers is not only comparatively strong in eastern Europe and Russia, but also in Austria. ‘Our money for our people’ is almost as popular in Austria as it is in eastern Europe. This finding explains why this political debate is popular in Austria and why Austrian elections can be won in this way,” says Fink.

Door opener for research cooperation

The Europe-wide coordination of PAWCER was undertaken by the Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences (GESIS). The project partners in Austria were the Institute for Advanced Studies (IHS) and the European Centre for Welfare Policy and Social Research. Leading research groups at the University of Leuven and the University of Tampere were also involved in the analysis of the data. For the IHS, where the financing and design of the welfare state has been studied for many years, the project became the starting point for a research strand dealing with public opinion. PAWCER opened the doors for cooperation with renowned institutions in these two thematic fields.

On the basis of the national ESS data, further projects were initiated. As the two topics have not previously been merged in an analysis, the interfaces of climate change and the welfare state are interesting areas for further research. Issues of distribution and social inclusion potentially exhibit strong mutual points of reference with the fight against climate change. Conflicting goals, individual effects, and interactions between the respective attitudes can be revealed in the process.

Marcel Fink has held a position as Senior Researcher at the Institute for Advanced Studies (IHS) since 2013. Previously, he was a university assistant at the Institute of Political Science, University of Vienna. He completed his doctorate in political science in 2002. In his academic and applied research, he has devoted the last 25 years to questions surrounding social policy, welfare state, labour market, poverty, and social inequality. The international project “Public Attitudes to Welfare, Climate Change and Energy in the EU and Russia” (2016-2019) was co-financed by the Austrian Science Fund FWF to the amount of EUR 181,000.

Publications

Pohjolainen P., Kukkonen I., Jokinen P., Poortinga W., Ogunbod ChA. et al.: The role of national affluence, carbon emissions, and democracy in Europeans’ climate perceptions, in: Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 2021

Gugushvili D., Ravazzini L., Ochsner M., Lukac M., Lelkes O., Fink M. et al: Welfare solidarities in the age of mass migration: evidence from European Social Survey 2016, in: Acta Politica, 2021

Ochsner M., Ravazzini L., van Oorschot W., Gugushvili D., Fink M. et al.: Russian versus European welfare attitudes: Evidence from Round 8 of the European Social Survey, PAWCER, ESS Topline Series, 2018 (PDF)

Pohjolainen P., Kukkonen I., Jokinen P., Poortinga W., Umit R.: Public Perceptions on Climate Change and Energy in Europe and Russia: Evidence from Round 8 of the European Social Survey, PAWCER, ESS Topline Series, 2018