Virus Monitoring: From High School Students to Researchers

How can we fight the flu? Or the spread of airborne pathogens? The coronavirus pandemic showed us clearly how important hygiene measures are in reducing the risk of infection. Thorough hand washing, wearing masks, or airing indoor spaces helped curb the spread of the Covid-19 virus. In addition, large-scale testing and real-time statistical analysis made it possible to monitor the pathogen’s progress. This was only possible if scientific principles and social responsibility went hand in hand.

Health literacy creates trust in science

Communicating complex research results to the population and implementing solutions does, however, require a certain level of “health literacy.” This term describes a person’s ability to find, understand, and apply health-related information. We need this skill, for example, to understand technical terms such as DNA or mRNA vaccines, or to understand the difference between PCR and antigen tests, words which characterized the vocabulary of the coronavirus era. But how many people are willing to actively engage with these subjects, and how successfully can these skills be taught? Skepticism and the decreasing level of trust in scientific research were palpable during the pandemic.

This tense situation was the inspiration for the Citizen Science project “Airborne Pathogen Surveillance with High School Students,” conducted by virologist Andreas Bergthaler and evolutionary biologist Orsolya Bajer-Molnár. Working together with teens, the project aims to monitor pathogens that spread through the air in schools. All participants are actively involved from the initial design of the project, to implementation, all the way through to documentation of the experiments. A further unique aspect of the project is the cooperation with social epidemiologists and sociologists. Together with the students, they want to identify social factors that further facilitate the transmission of infectious pathogens.

The one-year project “Airborne pathogen surveillance with high school students” (2024–2025) is awarded EUR 50,000 in funding by the Austrian Science Fund FWF in the "Top Citizen Science" funding program.

Teens as both samplers and researchers

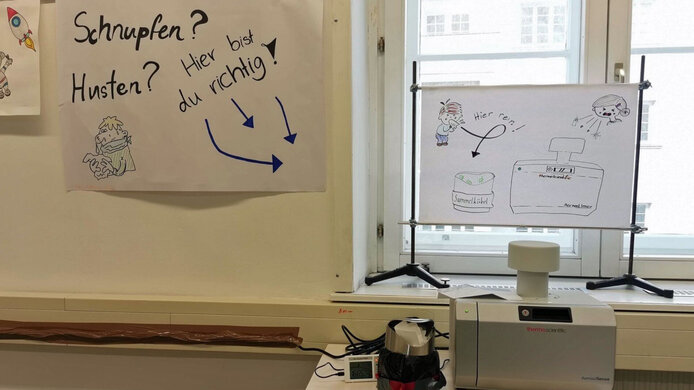

The project is funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF). Around 50 high school students from six Austrian schools are participating. The sampling phase of the one-year project, which will run until spring 2025, has already been completed. Three different sample series were collected per school: Pathogens were sampled directly from the air using an active air filter, from used paper tissues, and from surfaces that are often touched, such as door handles or light switches. The rooms and surfaces included in the sampling were determined with the help of valuable input from the students.

The students were also actively involved in the collection of samples. Their responsibilities included planning the sampling schedule and locations, replacing the air filter cartridge daily, collecting tissues over a four-week period, and entering metadata into an online database. In the next step, the research staff analyzed the samples in the laboratory and the results were communicated to the students. During workshops at the Vienna Open Lab, the teens learned how to carry out RNA extractions and PCR tests. “Our aim is not just to use the students as samplers, but also to get them involved in the experiments on a conceptual level and get their constructive feedback,” says Andreas Bergthaler.

No cooperation without trust

While the project has officially been running since January 2024, preparations and the recruitment of participants began the year before. During this time, teachers and students were able to get to know everyone involved, attend events to learn about the steps planned for the project, and gain mutual trust. Orsolya Bajer-Molnár is largely responsible for the organization and planning of these events.

According to the evolutionary biologist, gaining teachers' trust in the project is key if the research is to succeed. To ensure this, the researchers communicate with the students on an almost daily basis using the communication platform Discord. This allows the team to address any problems that may come up in real time, says Bajer-Molnár, as well as strengthening participants’ commitment and the sense that they are working together as equals.

Scientific and socio-epidemiological relevance

The transdisciplinary project is expected to produce findings in several fields of research. On a natural sciences level, collecting data on pathogens in public and crowded places, such as school cafeterias, provides valuable insights into the development of current pathogen populations and the health risks they pose. Among other things, this may reveal the number of asymptomatic disease carriers, a question which has remained unsolved since the halt in universal PCR and antigen testing, despite its significant impact on disease spread and development.

In the second part of the project, the focus is on social epidemiological surveys, recording evidence on the relationships between social factors and health status. The students will also be asked how much they know about infections before and after the project, for example on contagiousness in the event of an asymptomatic course of the disease and on preventive measures such as regular ventilation. The survey results should show whether the knowledge corresponds to the pathogens found and what conclusions can be drawn. Students’ work on the project counts towards their required pre-academic thesis.

Is enthusiasm contagious?

And how has students' relationship to science and research changed since the pandemic? This is a further question the researchers want to follow up on in interviews. At the end of this innovative, participative project, the students who contributed most to the research will also be named as co-authors of an academic paper on the work. The real accomplishment, however, will be getting the 50 participants to act as multipliers in their schools, interacting and communicating with students who were not directly involved in the project. “Ideally, this type of highly advanced Citizen Science project will be a kind of blueprint for similar projects in the future,” says Bergthaler. He and Bajer-Molnár hope to make science even more accessible to all levels of society and to pique people’s interest in the search for unanswered questions. And who knows, maybe a student or two will be inspired to pursue a career in research?

The researchers

Andreas Bergthaler’s research at the Medical University of Vienna focuses on immunology and infectious diseases. Bergthaler and his team are particularly interested in systemic immunometabolism, pathophysiology, and modern pathogen monitoring.

Orsolya Bajer-Molnár works at the interface between the evolution of pathogens and public health policy. Her field of expertise is the development of new forms of communication and participatory approaches in citizen science to help more people understand preventive health measures for infectious diseases.