The unknown chants of Byzantium

“If you open your hand, they will be filled with good things.” These words were chanted at the beginning of the daily evening service in Byzantium. This type of psalm – the term is used to describe poetic, short texts from the Old Testament – also plays a role in the Western Church. But in the Orthodox tradition their significance is vastly greater. Set to music, they are to this day a structural element of liturgical rites – especially of the offices structuring the day, such as Matins or Vespers. The psalm quoted above, Psalm 103, 28 (104 according to the German ecumenical bible translation), was followed by a number of other biblical texts set to music in the evening office.

The melodies underlying these psalm chants of the Eastern Church between the 10th and 14th centuries are at the centre of Nina-Maria Wanek’s current research. In her project on “Psalm composition in middle and late Byzantium”, which is funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF, this musicologist, Greek scholar and Byzantine researcher is planning to produce the first systematic history of the melodic patterns that were associated with the psalms at the time. “In the course of my work, a number of further research questions arising in this context will also be explored – such as how static or changeable these early psalm melodies turned out to be over the centuries,” Wanek explains.

Different cultures of faith in East and West

The Eastern and Western Churches went down separate paths early on. After the Roman Empire crumbled in the fourth century, the faithful in the West who considered Rome their capital, gradually accepted the Pope as the head of all Christendom. In the Eastern Roman Empire, on the other hand, the Patriarch of Constantinople was considered the leading figure of the church. After centuries of conflicts, the final schism between Eastern and Western Churches occurred in the 11th century. At that point, two very different Christian faith cultures had already been evolving for a long time. Latin was the church language in the West, whereas Greek was used in the East. There were differences in church customs, but also in substantial questions of faith – including the role of the Holy Spirit – between the Western and Eastern Churches, which were later to transition into the Roman Catholic and Protestant churches on the one hand, and the Orthodox Churches on the other.

One of the differences even back then was the great importance the liturgy of the hours had in the Eastern Church. “In this context, psalms have a special significance. In the Middle Ages, a complex system of rules developed, which assigned specific psalms to each liturgical celebration; some of them were recited, but mostly they were sung,” Wanek explains. “In the medieval Western Church, psalms were also sung, but their structuring role was not as pronounced as that of their Eastern counterparts.” The Gregorian chants of the medieval Western Church are known to this day; they can be seen as an equivalent to the psalm chants of the Eastern Church.

Transcripts of embellished chants

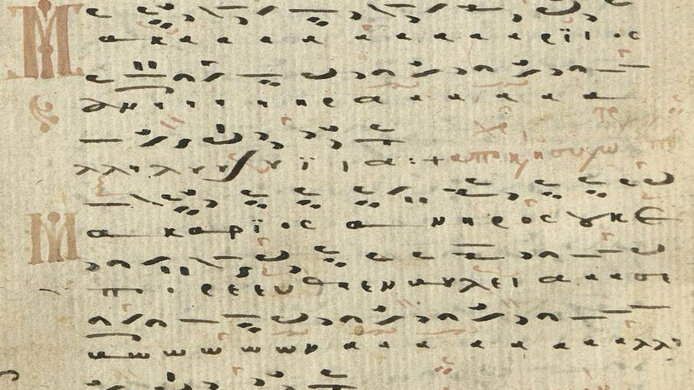

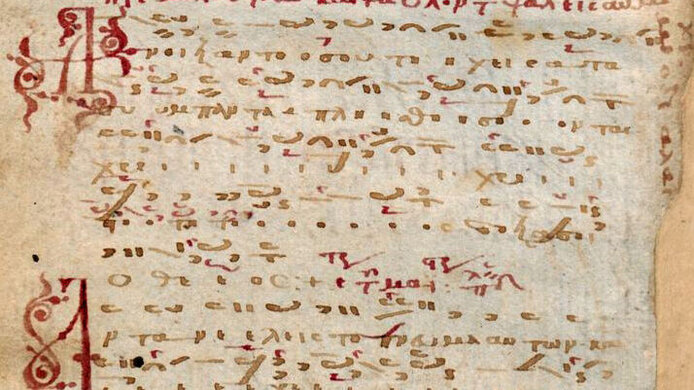

“There are only very few written records of the early psalm chants used before the 14th century. These include the Anabathmoi, the so-called Gradual Psalms, which can already be found in manuscripts from the 11th century,” Wanek notes. “Conversely, from the 14th century onwards there are detailed transcriptions of the psalm chants – probably because at that time people began to expand the melodies to a great extent and add numerous embellishments, so that it was no longer possible to know everything by heart.”

Wanek now wants to find out more about the early, comparatively unknown melodies. “These psalm chants were probably very simple, which is why we also speak of ‘simple psalmody’,” she says. The comparative approach is one of the most important methods the musicologist uses in her research. “My work involves in-depth comparisons between melodic patterns from early and later sources. The idea is to find out how much of the old melodies is still preserved in the newer variants.”

Traditional singing, which was subject to few changes

In Byzantine society it was important to preserve traditions – even in music. “Melodies were passed down from generation to generation. There was no demand for innovation, compositions included little that was fundamentally new, instruments and polyphony were forbidden then and are still forbidden today in the Greek church,” says Wanek, outlining the cultural context. “The embellishments called ‘melismas’ – today they would be called coloraturas – of later melodies that were handed down make the pieces longer and more playful, but for the most part still preserved the core of the old, orally transmitted melodies.”

Against this backdrop, Wanek felt that she should also work on reconstructions and use existing sources to infer information about the earlier songs. “It’s like having a sprawling opera based on a song like Baa Baa Black Sheep – complicated by the fact that you don’t know the song. The challenge you now have is to identify that simple melody and distil it out by paring down all the exuberant ornamentation,” is how Wanek illustrates the challenge she confronts.

Singing “Hagia Sophia style”

The ultimate goal is to produce a historical outline that covers the period from the 10th to the 15th century. An annotated, systematically organised corpus of melodies is designed to produce a scientifically sound overview of the psalm melodies of this period. In addition, Wanek wants to investigate the influence of liturgical developments – for example, the merging of various cathedral rites of monasteries and cities in the late 14th century – on the development of psalmody. In the process it will be helpful to establish comparisons with other genres of chants of the period, or between melodies attributed to different geographic regions, since some of the surviving formulas have indications such as “Athos style” or “Hagia Sophia style”. Wanek would like to find out whether these indications are actually designations of origin, perhaps referring to local traditions, or whether they have other meanings.

With her research, Wanek wants to lay a foundation that will make it easier for scholars to deal with this subsidiary area of Byzantine culture in the future. After all, one of the biggest obstacles to research in this field is the fact that sources are not readily available. “Unlike in other disciplines, there are no databases that bring together original sources that are scattered all over the world. Important manuscript collections are only accessible on the spot. There are documents on microfilm in Greece that were created in the 1930s and are therefore in poor condition. There are probably holdings on Mount Athos, which, as we know, is inaccessible to women,” Wanek notes. “This difficult situation concerning sources is partly responsible for the fact that very few studies exist, not only on psalmody, but also on Byzantine music in general.” She would like to contribute to drawing more scholarly attention to Byzantine music. After all it was added to the Unesco list of intangible world cultural heritage in 2019. Wanek is convinced that this would also benefit the study of Western medieval music.

Personal details

Nina-Maria Wanek has been researching Byzantine church music as well as modern Greek art music of the 19th and 20th centuries for more than twenty years. She received her doctorate from the University of Vienna and in 2006 acquired the professorial qualification in historical musicology. Wanek teaches at various institutions, including the Institute for Byzantine and Neo-Greek Studies at the University of Vienna. She also works as a translator for Modern Greek literature. Her project on the “Composition of Psalms in Middle and Late Byzantium” has been running since 2020. It is funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF with EUR 330,000.

Project website: www.byzantinemusicology.com

Publications

Nina-Maria Wanek: Blessed is the Man … who Knows how to Chant this Psalm: Byzantine Compositions of Psalm 1 in Manuscripts of the 14th and 15th Centuries, in: Clavibus Unitis 9/4, 2020 (PDF)

Nina-Maria Wanek: Überblick über die byzantinische Kirchenmusik, in: Ex Oriente Lux? Ostkirchliche Liturgien und westliche Kultur (H.-J. Feulner/A. Zerfass, Hg.), 237–264, Wien 2020