The transformation of secret services

Although the very term “secret” in the name of any institution suggests it may present a challenge to researchers, that did not deter Verena Moritz from the Institute of Eastern European History at the University of Vienna. This historian, who also learned Russian as part of her studies, is working on the history of the secret services and more specifically on the military intelligence service of the Habsburg monarchy. That service went by the name of Evidenzbureau – which translates as something like “agency keeping information readily at hand”. In her current FWF-funded research project, Moritz is investigating the development of the Evidenzbureau and its activities relating to Russia, Austria-Hungary’s main enemy in the roughly 50 years leading up to the First World War.

While intelligence activities have existed since ancient times, they were more of an ad-hoc nature for thousands of years: reconnaissance units were set up for individual military campaigns and then disbanded. The first step towards professionalization occurred during the Napoleonic Wars, when all of Europe was in a state of war for more than 15 years. “Tremendous change in social and political terms then came in the 19th century,” Moritz notes. The emergence of nation-states, immense technological progress, the birth of a widespread popular press, universal conscription: it was a “transformation of the world,” to borrow the title of a famous book by historian Jürgen Osterhammel on the 19th century. And the intelligence services changed along with that world.

Recent intelligence research closes gaps

If the prevailing opinion in intelligence research maintained for a long time that the essential development towards modern intelligence services occurred shortly before the First World War, it was also because there was not a great deal of expertise on the subject. “The evolution of modern intelligence was rather neglected by research,” Moritz explains and notes that such research has only taken off in the recent past. By now, knowledge on Russian, but also French and German, intelligence has grown considerably. “Austria-Hungary is one of the biggest gaps. That's where my research comes in.”

Austria (and later Austria-Hungary) was a pioneer in intelligence due to the mid-19th century conflicts with Prussia for supremacy in the German Confederation. The period was marked by tensions between the two major powers, which eventually led to the decisive Battle of Königgrätz (Sadowa) in 1866. At that time, Austria felt the need to enhance and expand the already institutionalized “reconnaissance system”, leading to the establishment of the Evidenzbureau, i.e. the military intelligence service in Austria and, later, in the Habsburg Monarchy.

Intelligence service grew with tensions in the Balkans

The task of the Evidenzbureau, which started out with little more than a dozen staff members, was to collect and evaluate information passed on to the military general staff – another invention of the 19th century. It was a “rather boring job,” as Moritz notes, and not a task that was popular within the army. Although the term “intelligence” covers a wider range of tasks than the term Spionage (espionage) does in German, the main part of both jobs involved information processing. New impetus then arrived with the development of modern cartography. Espionage, i.e. activity involving men with fake moustaches, also existed, but it was by no means the central task of military intelligence services.

After the German question was settled and the Habsburg Monarchy had become established, tensions shifted to the Balkans. Russia, which also had interests in the region, became the main opponent. In the 1880s, when disputes such as the Bulgarian crisis occurred, the reconnaissance services greatly expanded their staff. The Bulgarian crisis also resulted in some institutional changes: the intelligence service needed information from the border region, where the threats were located. This was also the onset of the involvement of civilian institutions, first the border guards, then customs officials and the gendarmerie. “This is a finding I was able to ascertain very clearly in the project: contrary to earlier beliefs, this involvement did not begin in the decade leading up to World War I, but earlier,” Moritz notes. It began as a matter of necessity: paid out of the budget of the foreign ministry, the secret service did not have enough personnel to handle its multitude of tasks. The Evidenzbureau's desire to extend its activities more and more to domestic issues also made it necessary to cooperate with non-military institutions.

More Russian than domestic spies

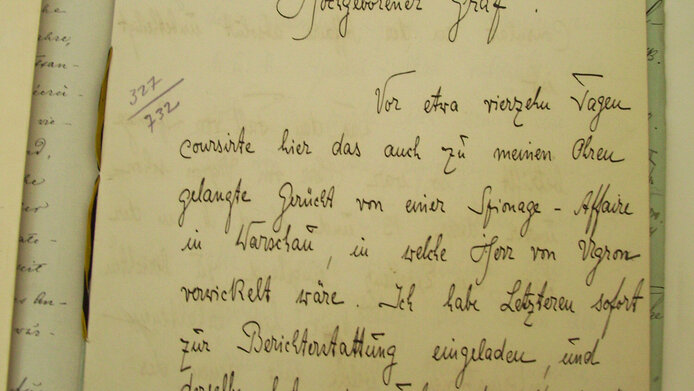

Even though Moritz was able to show that many activities began far earlier, intelligence work did indeed develop a new quality in the decade before the First World War. The number of espionage cases increased by leaps and bounds, and Galicia (today part Polish, part Ukrainian) turned into a hotspot. The Russians had more spies among the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy’s officers than vice versa. Developments culminated in the famous case of Colonel Alfred Redl, who occupied a leading position in the Evidenzbureau and was a Russian spy at the same time. In 1913, Redl was unmasked and committed suicide. “I was actually surprised by the number of espionage cases I was able to investigate as part of the project,” Moritz reports. Most of these, however, were “small fry”, and did not compare in significance to that of Redl. Moritz was also able to identify two other interesting facts. First, almost all of these spies offered their services of their own accord. Being recruited by opposing intelligence services played only a minor role. “Most of these officers had no political motives at all,” Moritz notes. “It was always a question of money.”

Personal details

Verena Moritz studied history and Russian in Vienna and wrote her thesis about Russian prisoners of war in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy during the First World War. Since 1998 she has been the principal investigator of several research projects on Russian/Soviet history as well as on the late Habsburg Monarchy and Austria from 1918 onwards. Moritz works at the Department of East European History at the University of Vienna. Set to run until 2025, the project “Austro-Hungarian Military Intelligence and Russia, 1867–1914” is endowed with ca. EUR 158,000 by the Austrian Science Fund FWF under its “Elise-Richter” program.

Publication

Verena Moritz/Wolfgang Mueller (eds.): Erkundungen. Militärische Nachrichtendienste, Spionage und Informationsbeschaffung vor dem und im Ersten Weltkrieg in Russland, Österreich-Ungarn Deutschland und Italien, Internationale Geschichte Vol. 8, Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften 2022