The sound of medieval music

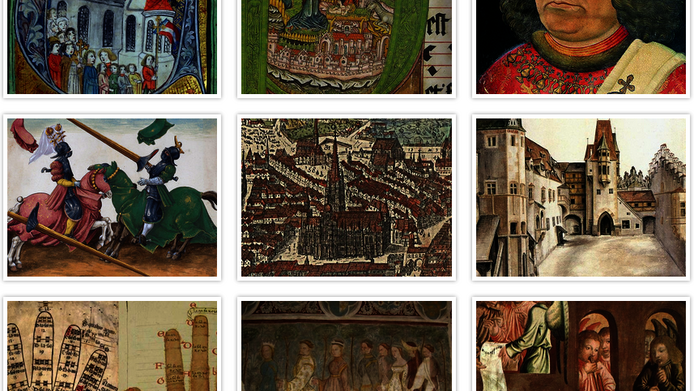

“During the late Middle Ages”, says Reinhard Strohm in the interview with scilog, “the city of Vienna was a place full of acoustic signals. The bells of the Minoritenkirche would call worshippers to prayer, vespers or mass, one would hear the bells of the St. Augustine sending forth their messages, noblemen would be passing through the city accompanied by fanfares; there were voices calling out, singing and praying everywhere.” And that was not even the whole story. Add to this the clatter of horses' hooves, the grunting of pigs, the clucking of chicken, the quacking of ducks, random squeaking, rattling, knocking, hammering, banging, clanking, calls, groans, cries, lamentations, begging and praying in every key and volume, and then some. The city in the late Middle Ages and beyond was a place of total acoustic cacophony. At least when judged from today’s point of view and listening habits. The soundscape of cities is only a secondary concern for Strohm, a musicologist at Oxford University. Together with Birgit Lodes, who holds the chair of Historical Musicology at the University of Vienna, he is primarily investigating a very different sonic sphere within the context of the FWF funded project Musical Life of the late Middle Ages in the Austrian Region.

Outshone by what came after

“We actually know comparably little”, explains Lodes, “about the music of that time. Not because nobody takes an interest in it, but because Vienna and Austria are so greatly marked by Baroque music and, even more, by the Viennese Classical School.” Together they represent the central constellation in the domestic music universe, outshining and defining everything else, including our listening habits. “Late medieval music sounds different”, notes Lodes. Less familiar, less like what we are used to. This is due also to the instrumentation. It is music from a different context, much more standardised than that of the Baroque era and a bit odd when considered in retrospect. This said, it is certainly not one-dimensional. “We have to take into account the range of possible variations”, notes Lodes. She occasionally tests her students, making them listen to one and the same piece, first in an instrumental version and then as pure choral music. “It is surprising how rarely they realise it is indeed the same piece”, says the music historian wryly.

Change comes with a fanfare

In a certain way, Lodes and Strohm and the other scholars involved in the project are also trying to do justice to the music and composers of an era that was essential for European intellectual life. Between 1340 and 1520, Europe set out for new horizons. New technologies end the era of knights, minor nobility is crowded out by a bourgeoisie on its way up, cities gain influence and the universities provide access to the knowledge of antiquity. Wars, epidemics and plagues rage, popes confront anti-popes and reformation challenges the church of old. No stone is left unturned in these 200 years. At the end of it, the Renaissance awaits. All of this is accompanied by music. “In that era, European music-making was no longer bound by national or regional borders”, explains Strohm. Music spread across Europe like wildfire. It took not even twelve months for the music composed for the enthronement of the Duke of Ferrara in 1441 to be received and written down in Vienna.

New popularity of old music

It goes without saying that Vienna also had its composers. So had Innsbruck, Wiener Neustadt, Graz or Salzburg. Even if there is often nothing left to be found of them in the archives, much to the regret of Lodes and Strohm. Still, every prince, and particularly the archdukes and emperors of the Habsburg dynasty, had his chapel, with musicians and singers, who accompanied the sovereign on his travels, proclaiming his fame and noble spirit (and complaining bitterly in their letters about miserly wages and dire living conditions). The investigations of Lodes and Strohm cause them to delve profoundly into the everyday life and living conditions of that era. “We are still busy implementing the essays of the project on our website www.musical-life.net”, notes Strohm, while Lodes points out that this project was often the motivation for a first recording of pieces of music that can now be listened to on the website. “There were even two CDs put together from these recordings which can now be bought”, Lodes happily relates. This is what the project is about for her, creating access, inciting interest and keeping it alive with an immense number of examples. An additional motivation is to pay tribute to musicians that might otherwise be forgotten, outshone by the composers of later eras.

Personal details Birgit Lodes was a visiting fellow at Harvard University, a lecturer at the Hochschule für Musik in Munich and stand-in for the C3 musicology professorship at the University of Erlangen-Nürnberg. In 2005 she was appointed to the chair of Historical Musicology at the University of Vienna. She is a corresponding member of the Austrian Academy of Sciences and a member of the Academia Europea.

Publications and contributions