The impact of education on family life

Being well educated is considered an essential prerequisite for financial success, prosperity and professional self-fulfilment. But the level of education also has a strong influence on a person's social behaviour. The amount of time spent at school and university has a variety of effects on relationships, family life and the interaction with one's children - which in turn has an influence on their opportunities in the future.

In Europe, very little research has been done on the question of how this connection between the level of education and family life develops in the long term and what differences exist between countries in this regard. The FWF-funded project “Families and Inequality: trends in the education gap in family-related behaviour across European countries” addresses this research gap. Together with an international team, Caroline Berghammer from the Department of Sociology at the University of Vienna and the Vienna Institute of Demography at the Austrian Academy of Sciences is analysing the correlations, which vary from country to country. The findings could also be relevant for social-policy considerations. For the question of what support services families should receive, for instance.

“Divergent destinies” in education and family life

A well-known trend, documented by a number of previous studies, indicates that people with higher levels of education tend to engage in a type of family behaviour that is more conducive to increasing their resources – both in term of economic interests and social needs: they become parents later in life, but then place a higher value on spending time with their children. Mothers are still more likely to be in gainful employment. Those who are less educated, on the other hand, are more likely not to marry their partners, to get divorced or to separate. “This phenomenon is particularly noticeable in the US,” Berghammer explains. “There we see that when it comes to family behaviour the gap between the more and less educated has widened in recent decades. In the US, for example, people with low education levels are very often single parents.” In this context, Berghammer makes reference to the US sociologist Sara McLanahan, who died in 2021. She coined the term “diverging destinies” to describe this development.

One also finds this pattern in Europe, but here the situation is marked by greater diversity. “We studied the correlations between education and family life in eight countries and across several decades: in Austria, Italy, Ireland, the UK, Poland, France, Germany and Norway,” Berghammer reports. “In this context, we analysed data from the Labour Force Surveys – large sets of data that are collected consistently across European countries and are available far back into the past. In part, we also combined these with census data from the statistical offices of the respective countries.” In some cases, she notes, it was difficult to access the data owing to differences in national regulations.

Influence of education on partnership status

According to Berghammer, a general trend reflecting social developments in the area of gender roles in Europe concerns the educational background of single women: “In the 1970s we see a positive educational gradient among single parents. Raising a child on your own was a new type of family behaviour at that time, one which forced you to go against conventional norms and which required a lot of resources. It was a path taken more often than not by the more highly educated. Then, in the 1980s, the trend reversed. More people with lower education levels became single parents.” Norway is the exception that did not follow this pattern. There, it was the poorly educated who tended to be single parents in the past; a situation that has hardly changed until now.

In countries such as the UK or Ireland, the trend towards rather low educated single parents – as in the USA – is still strong today. There are hardly any educational differences among single parents in Italy or Austria, for example, according to a country comparison by Berghammer. And the circumstances that prompt someone to be a single parent also differ: “In the UK, Ireland or Poland, very high proportions are single parents right from the birth of the child, with the number of teenage mothers also playing a role. In Austria, these phenomena are less pronounced. All in all, children are on average around seven years old when a parent becomes a single parent.” Besides cultural differences, socio-political circumstances could also be responsible for the differences. Berghammer: “We suspect that the differences may inter alia be caused by different degrees of public welfare.”

Enough time for the children?

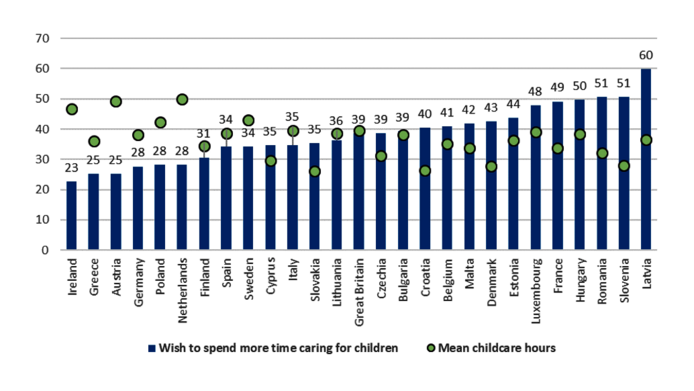

Another study that emerged in the course of the project explores the question as to whether parents feel that they are spending enough time with their children. “Across Europe, fathers are far more likely to say that they spend too little time with their children. But it’s by no means rare to hear this also from the mothers,” notes Berghammer. “In Austria, about one in four mothers say they spend too little time with their children. That is little in comparison with Southern and Eastern Europe, where labour markets are more rigid and offer fewer part-time jobs or opportunities to work from home.” It is striking that the more highly educated set higher standards for themselves: “Their ideals and behavioural norms result in a child-raising behaviour that is much more intensive and requires more resources than in the past. This tallies with the fact that the more highly educated also more often feel that they spend too little time with their children – even if it is as much as the people in the less educated group.”

Person

Caroline Berghammer is an assistant professor at the Department of Sociology at the University of Vienna and a research associate at the Institute of Demography at the Austrian Academy of Sciences (ÖAW). Previous research stays abroad have taken her to Princeton University, the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of Toronto. Her project “Families and Inequality: trends in the education gap in family-related behaviour across European countries” which receives EUR 230,000 in funding from the Elise Richter Programme of the Austrian Science Fund FWF, is set to run until June 2022.

Project website: https://fate-project.at

Publications

Berghammer C., Adserà A.: Growing inequality during the Great Recession: Labour market institutions and the education gap in unemployment across Europe and in the United States, in: Acta Sociologica 2022

Berghammer C., & Milkie MA: Felt deficits in time with children: Individual and contextual factors across 27 European countries, in: The British Journal of Sociology, 72, 1168–1199, 2021

Berghammer C., Matysiak A., Lyngstad T., Rinesi F.: Change in the educational gradient of single mothers since the 1970s across European countries: a family life course approach. Conference presentation at “II Data Forum on Harmonization and Uses of European LFS Microdata”, Barcelona, 2020 (PDF)